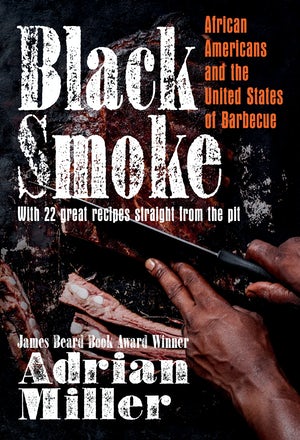

Miller, Adrian. Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States Barbecue. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2021.

I am a huge fan of barbecue. I don’t know precisely when I became one, but it certainly become the case by high school, when I was making sauces while my dad smoked ribs or pork shoulder or brisket on his Weber outside on our deck. My love for this unique American cuisine has only grown over the past two decades, from sampling any restaurant remotely close by to even taking my own first steps into making what dishes I can. Seldom, however, have I learned much of the history of barbecue, however, and so when I chanced upon such a history (from one of America’s most respected academic presses, no less), I could hardly leave it on the shelf.

Adrian Miller’s Black Smoke begins with a simple observation: barbecue, which has for hundreds of years been associated with the black community, has become whitewashed in recent decades as its popularity has brought it to the fore of American haute cuisine. I confess, I’m not plugged in to much contemporary food media, but his assertion certainly did not surprise me, given America’s penchant for whitewashing just about anything. To combat this recent trend, Miller conducts his readers through the history of barbecue from its possible beginnings with Native American and West African open-flame cooking techniques to the era of plantation barbecues through to the great barbecue entrepreneurs of the 20th century and innovators of the 21st.

Miller’s telling of that history is masterful (if sometimes a bit informal for my tastes), and in its course I realized just how much I did not know, and how much history has been lost in the current interpretation of barbecue—precisely his point. His accounts of barbecue masters supervising efforts to feed hundreds, even thousands, of people in a single day for the great political and social gatherings of the late 19th century never fail to impress, and even more recent history emphasizes the different worlds of ‘cue; ribs, for example, have classically been the focus of what African Americans consider barbecue, and contrary to much modern wisdom, the old black masters traditionally cook their meat at an initially high temperature before then moving to the current “low and slow” wisdom. Even more valuable than the specific culinary history of barbecue is Miller’s deft emphasis on its importance to black culture. Barbecue was, by turns, a possible source of income for enslaved people, a symbol of resistance against slave owners, a proud heritage of generational prestige and wealth, and the centerpiece of both religion and community activism. It’s not often one can persuasively argue for a single cuisine’s centrality to history, but Miller does so in spades.

Perhaps the most unfortunate side of Black Smoke lies not with Miller’s history, but in the present the reader arrives at. A whole host of challenges face modern barbecuers, especially those of color, and it can be depressing to read (and discover oneself) the long list of black-owned barbecue stands, shacks, and restaurants that have closed in the past two decades or, worse yet, never got off the ground. While Miller’s profiles of 21st century barbecue innovators does give hope for the future, even they have not been immune to economic woes, and one can only hope that black barbecue has as bright a future as Miller clearly hopes it does.

For those who love the smell of smoking meat or the tang of a good sauce, I cannot recommend Black Smoke highly enough. While many of its included recipes are far beyond me (I don’t think I’ll have the capacity to do a whole-hog roast any time soon), I’m sure I won’t be able to avoid reflecting back on its contents every time I chow down, now and far into the future.