The sixth year of Concerning History has come to a close, and in our annual tradition, our staff reflected on the noteworthy anniversaries that have come and will come this year.

1773: 250th Anniversary of the Boston Tea Party

Francis Butler

This December will mark the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, one of the most well-known events in American history. On that fateful night of December 16, 1773 a crowd of disgruntled Bostonians boarded three different East India Trading Company (EIC) ships to destroy over 400 chests of tea stored within them. While myth casts this as a heroic act of rebellion against oppressive taxes and British tyranny, the historical reality was much more complicated. Anglo-Americans were actually the least taxed subjects of the British Empire; their problems with taxation instead had to do with which level of government (colonial or imperial) had the power to tax and why. In the case of the Boston Tea Party, British tea was actually cheaper than all other foreign teas even with a tax; Bostonians rallied to protest not just the tax on EIC tea but the EIC’s government-sanctioned monopoly on the sale and distribution of that tea–without any input from their elected colonial assemblies.

The Boston Tea Party also serves as a reminder that the colonists were just as violent and destructive as they claimed the British to be. That night, Anglo-American colonists invaded the property of a British corporation, destroyed a great deal of valuable property, and then walked away with no punishment. This event sparked “tea parties” in other colonies, too. Prior to the Boston Tea Party, British loyalists, tax collectors, and officials were also subjected to communal violence: tarred and feathered, imprisoned, or assaulted by local Committees of Safety, institutions that the First Continental Congress authorized to police suspected loyalists. One can only imagine the outcry if such indignities were inflicted upon a modern corporation or local government.

Recommended Reading: American Patriots, American Insurgents, by T. H. Breen

1823: Declaration of the Monroe Doctrine

Two hundred years ago this December, President James Monroe delivered his seventh annual message to Congress. It had been eight years since the conclusion of the War of 1812, and many issues of international relations still faced the young nation: finalizing the border between the United States and Canada, arbitrating financial losses incurred by the French during the course of their Revolution, shutting down the Atlantic slave trade, even the status of American nationals in Russian territory. After detailing these ongoing efforts at diplomacy, Monroe concluded with the sentiment that “the occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.”

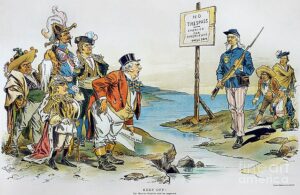

Historians generally agree that what became known as the “Monroe Doctrine” was primarily aimed at preserving the sovereignty of the newly-independent Latin American republics from renewed European efforts to bring them to heel, but at the time Monroe was writing checks his paltry standing military couldn’t cash. For the doctrine’s first half-century, its true enforcer would in fact be Great Britain, who had not lost any colonies through these independence movements and was perfectly happy to economically colonize the Western Hemisphere–South America was second only to India in British imports and exports in the 1800s, not to mention the extensive British financial interests in those countries. In the late nineteenth century, however, a newly-empowered United States began twisting the intent of this seemingly-anticolonial doctrine from a rejection of European imperialism to an embrace of American exploitation, forming a sphere of influence over Latin America through both financial and military coercion that some historians have argued approached the formal control exerted over the island empire gained through war with Spain in 1899. In today’s supposedly anti-imperial world of nation-states, the literal text of the Monroe Doctrine would seem to have limited relevance, but its effects can still be felt in the American assumption of primacy in the Western Hemisphere–for good and ill.

Recommended Reading: The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World System, 1830-1970, by John Darwin

1973: Paris Peace Accords and Operation Homecoming

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet Nam, more commonly known as the Paris Peace Accords. Out of the agreement came plans for the release of prisoners of war (POWs). American POWs who had endured the inhumanity of captivity for as many as eight years at long last received news they’d only dreamt of and could scarcely believe: freedom was theirs.

Carefully crafted to ease the transition out of internment, Operation Homecoming would shepherd 591 POWs home in 1973. Freed American servicemen and civilians were flown first to Clark Air Base in the Philippines before stopping in Hawaii and then on to Travis Air Force Base in California. From Travis, they would be flown throughout the US. Released military POWs received medical care, toiletries, fresh uniforms, and a $250 cash advance to be “deducted later from accrued pay.” (Civilian POWs also received medical care, provided they complied with the US military command not to speak with the press about their captivity or release.) Each freed POW was partnered with an active serviceman of their same rank, background, and interests to escort them through testing, contacting family, and planning next steps. The 31 military hospitals throughout the US that expected to treat the POWs were provided with resources for POW reintegration to society, including “‘year’ books for each year, the World Book, 60‐minute sport and news films, several films on the space program, a glossary of slang and the synopsis of news stories January 1965–June 1971.”

Despite best efforts to cushion the transition, though, POWs came back to a turbulent homefront. Operation Homecoming brought 591 POWs home, but loved ones of 58,220 military dead mourned the homecomings they would never see. Anti-war sentiments still rankled, servicemen shipping out to Southeast Asia expressed discontent, and an underground paper published outside Travis Air Base posed the question “P.O.W.’s FROM ONE PRISON TO ANOTHER?” Furthermore, the demographics of those included in Operation Homecoming skewed heavily toward white commissioned officers, with only 10 black POWs and no draftees. Fifty years later, we continue to grapple with the war in Vietnam, and POW release and reintegration only adds complexity to an already contentious conflict.

Recommended Reading: Voices of the Vietnam POWs: Witnesses to Their Fight, by Craig Howes

From the Treaty of Lausanne to Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch to the founding of Disney (all the same year, 1923, by the way) to the desgregation of the US Military, Good Friday Accords, and assassination of Ghandi, 2023 is an incredibly significant year for anniversaries. We could only scratch the surface here, but sound off in the comments about others we might have left out!