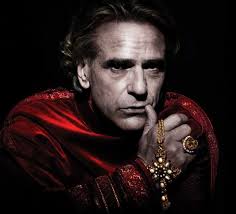

Last week, I reviewed Showtime’s The Borgias in tandem with Christopher Hibbert’s The Borgias and their Enemies. When I finished Hibbert’s work, I was struck by The Borgias’ choice to portray its titular family as the heroes of their own story. I am no Renaissance historian, but from the sources presented by Hibbert, it would seem that most contemporaries agreed that the Borgia family was a blight upon Italy, Christianity, and all humanity. Indeed, the tagline for the show is “History’s First Crime Family!” Sure, every member of the family is shown doing reprehensible things, but by virtue of the show’s narrative structure, they seem more excusable or, at least, less reprehensible than the actions of their enemies. Even the show’s numerous antagonists seemed mis-characterized; Cardinal della Rovere condemns the Borgias for corruption, yet historically, this future pope was no less corrupt, and possibly even more so! Why these character choices, some so at odds with history? As I pondered, I realized that I had already stumbled onto the answer to my questions: narrative structure and, specifically, our need for protagonists in our stories.

If you would indulge me for a moment, a tangent: human beings live for their heroes. Our earliest literary and mythic traditions revolve around heroes, from Gilgamesh to Odysseus to Aeneas. In the modern age, we students of history all have our heroes, and it is this hero worship that leads to so much rancor when one such hero is questioned, attacked, accused of being something less than a hero, something more akin to a complicated, morally ambivalent or even repugnant human being. Once you attempt to relate historical events in a fictional narrative format, you have combined these two human tendencies to potent result. In the specific case of the Borgia family, history would tell us that they were no better or worse than all the other opulent, corrupt, conniving, murderous families jockeying against them. A story, however, is nothing without someone to identify with. Game of Thrones doesn’t work without the honorable Stark family, stymied and wronged by the liars around them, for the audience to root for in the end.

History is not so convenient, but it can and has been made to be so. Even when media attempts to achieve some sort of grey area, the magic of the protagonist still prevails. Main characters that commit crimes in service of an ultimately defensible goal are antiheroes, not villains. The cast of History Channel’s Vikings slaughters innocents and commits human sacrifice, yet we root for them to overcome their neighboring warlord. Even if writers take pains to maintain moral judgment, as they may well have done on The Borgias, it fails simply because of the nature of protagonists. They are who we spend the most time with, whose trials shape the story we watch, whose personalities make or break the narrative. In an ironic twist, how could we root against these characters we’ve come to know so well, who feel so much like us, just separated by centuries?

This is not the first time I’ve reflected on historical accuracy in media, and I suspect it will not be the last. When I’ve exhausted myself on this topic, you might find a bound volume of all the reasons historical fiction is inherently inaccurate and a misrepresentation of the past for our own comfort. As an historian, I cringe at this fact, but as a lover of stories, I can’t help but shrug it off. Sure, stories might not reflect the realities of the past, as far as we can gather them, but that shouldn’t ruin our enjoyment of them. It is the ability to recognize those inconsistencies, call them out, and acknowledge that while figures might not be reprehensible by the standard of their own times, the difference between our moral standards and theirs is what makes history, well, history.