Last month, Bryan introduced a series of posts on Concerning History where we put forth our ideas and thoughts on parts and eras of history we would love to see adapted for the small screen. Living as we seem to do now in a golden age of television programming, I am thrilled to consider these sorts of possibilities. While only in my wildest dreams would I ever expect any of these subjects to actually make it to television, we can always hope! As I present my suggestions, my personal interests will become abundantly clear: if you too are a fan of political history and intrigue, this is most likely a list for you.

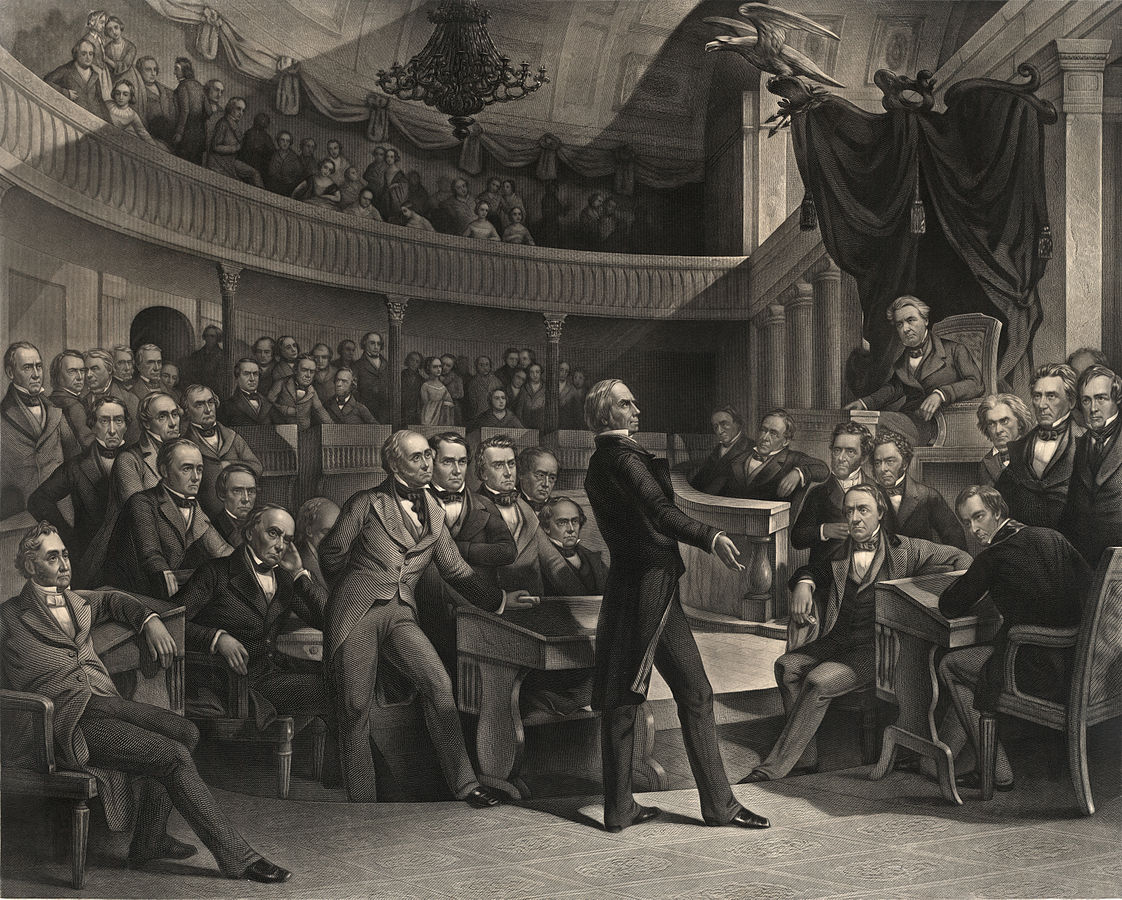

The Life of Senator Henry Clay: Henry Clay was born in the midst of the American Revolution, into a country whose future independence seemed uncertain. He witnessed his Virginia home raided by British soldiers in his youth, and later studied law under George Wythe, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and teacher to Thomas Jefferson. Clay is not a figure of the Revolutionary Era, however: rather, he led the vanguard of the second generation of American politicians, those charged with the heavy responsibility of leading their nation after the founders were gone. And lead he did, entering Congress for the first time at the age of 29 in 1806, and serving in a variety of capacities including Senator, Speaker of the House, and Secretary of State until his death in 1852. Over the course of his immense career, he built a reputation as “The Great Compromiser” from his significant role in defusing political conflicts that foreshadowed the approaching Civil War, such as the Missouri Compromise, the Nullification Crisis, and the Compromise of 1850. All the while, he remained one of the most partisan figures in Washington, serving as the intellectual godfather of the Whig Party, founded in opposition to the policies of Andrew Jackson. Three times he ran for President, and three times he was defeated, though each time coming closer to victory than the last. In 1844, his final presidential defeat was in large part brought about due to his opposition to the annexation of Texas, which he believed would lead to war with Mexico. Upon the election of his opponent, James K. Polk, it did, beginning the Mexican-American War: a war in which Clay’s eldest son would serve and die. Continuing to list his political achievements and accomplishments would merit a blog post all of its own, for even in an era filled with politicians who built immense, decades-long careers, Clay stands out among them for the sheer breadth and depth of his experiences, which earns him a greater place than most presidents of his time in the history books. Clay worked tirelessly to strengthen the young United States and prevent sectional tensions from rending the country apart — as they would less than a decade after his death. And though his presidential ambitions were defeated time and time again, many of the policies he pioneered would later be implemented by Abraham Lincoln, who viewed Clay as a model statesman.

As a series, The Great Compromiser could take cues from HBO’s John Adams, checking in at the most interesting stages of Clay’s career, including his family life and personal conflict regarding slavery. Looking at the conduct of Congress now and over the past several years, it is difficult to believe that it ever once functioned as the world’s greatest deliberative body, as paralyzed as it is by partisan gridlock. Perhaps we are in need of The Great Compromiser to remind us how Congress should work. It could tackle certain difficult political topics as well from the point of view of a man of the era who was nevertheless relatively uncomfortable with both: Manifest Destiny and slavery. Clay’s point of view would also give us sight on the troubles of the decades that led to the Civil War, which frequently go overlooked in favor of the war’s military drama, despite their immense significance to American history.

Recommended Reading: David and Jeanne Heidler, Henry Clay: The Essential American.

The Congress of Vienna: Few today would describe meetings between global leaders, such as the G20 Summit, with adjectives such as glamorous or exciting — they are business affairs where leaders come together, sternly shake hands, produce a few clever quips at best, and depart to carry on with their responsibilities. Th Congress of Vienna, which brought peace back to Europe following the Napoleonic Wars, was anything but a staid affair, however. Rather, the “Dancing Congress” was a glittering extravaganza the likes only imaginable when all of Europe’s greatest egos gather together for a six-month long festival of trying to out-do one another at every conceivable activity, from love to diplomacy. The two largest personalities in the room were likely Prince Klemens von Metternich, the youthful and energetic Austrian foreign minister who chaired the affair, and Tsar Alexander I of Russia — superstitious, bombastic, and absolutist — who fancied himself as Napoleon’s vanquisher. Politically, the challenges of the Congress were to reset the European political table that Napoleon had so thoroughly flipped, along lines that Metternich hoped would establish a balance of power to prevent a new Napoleon from ever rising up again. With the Tsar seeking only to strengthen Russia, however, and with the other successful powers of Europe constantly squabbling over the precise details of the peace settlement, the idea of a lasting peace was still much further away than many hoped. Meanwhile, the wildcard among the major European delegates was Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, the inscrutable foreign minister of the restored French monarchy constantly fighting an uphill battle to ensure that the vindictive powers allowed France to retain her seat among the great powers of Europe. And though the political negotiation was the main purpose of the Congress, the delegates amused themselves to no end with all the charms that Vienna had to offer, as Europe’s greatest artistic and culinary talents came to the city both to ensure the comfort of its legion of guests, but also to serve as weapons in the ongoing war of words intrigue between the gathered powers. The conclusion of the Congress of course comes with the shocking twist that is Napoleon’s flight from Elba and return to France, the allied armies marching against him even as the diplomats put the finishing touches on their outline for peace.

Once again, HBO seems to be the ideal vehicle to deliver this series: who else would be able to so perfectly capture the extravagance of the gathered powers … as well as the great deal of romantic affairs conducted in Vienna (with Metternich and Tsar Alexander quite literally competing to win over the affections of the other’s mistresses). Though the political drama of European politicians just over two-hundred years ago seems irrelevant and obscure to American audiences, the Congress did, in the end, successfully chart the path of much of European history for the following few decades. The peace established a balance of power that prevented war on the scale of the Napoleonic Wars from breaking out for almost a hundred years, until the First World War shattered that old order. Perhaps it is worth looking back to that era now, for a view at how peace is made rather than our seemingly unquenchable desire for war.

Recommended Reading: David King, Vienna, 1814: How the Conquerors of Napoleon Made Love, War, and Peace at the Congress of Vienna

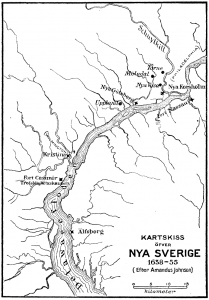

New Sweden and New Netherland on the Delaware River: I admit to some personal bias with this one, as this topic was an extensive part of my undergraduate thesis, and I’d love to see my research become relevant outside of the fairly obscure topic it dealt in, but nevertheless — I think it could work. Sweden’s attempt at colonization in the New World lasted only for a few decades in the mid seventeenth century, and focused on Delaware River Valley in modern day Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and (naturally) Delaware. During that time, they clashed frequently with Dutch colonists, who while centered around their primary colony in New Amsterdam, also laid claim to the land the Swedes settled on. All the while, of course, the land was primarily populated by the local Lenape population, also known as the (again unsurprisingly) Delaware Nation. In 1632, before the Swedes even arrived, the Dutch had tried to settle a colony in the south of modern Delaware that they called Swanendael in, which quickly ended in disaster when a dispute with the native population spiraled out of control, leading them to attack and destroy the Dutch colony. When the Swedish arrived five years later, they were led by Peter Minuit — the former director of New Netherland, who had fallen out of favor with his native government in the intermittent years, and so sought employment elsewhere. Minuit immediately set himself to befriending the Lenape natives, both to avoid a similar disaster as occurred at Swanendael, but also to secure a valuable trading partnership, which infuriated the Dutch in New Netherland. In the years that followed, the Swedes took advantage of their superior relations with the Lenape to help secure their colony, allowing them to compete with the financially stronger Dutch colonies, whose relations with the Lenape and other surrounding natives had declined to warfare. This began to change, however, when Peter Stuyvesant became Director of New Netherland in 1647, who made it his policy to undercut the Swedish-Lenape relationship and build a stronger presence on the Delaware River. He was supported in that regard by a Lenape sachem called Mattehoorn, who had grown wary of the Swedes’ growing influence. This three-way struggle for dominance continued for a number of years, as the Lenape sought to play both European colonies against each other for their own advantage, until Stuyvesant harnessed his superior military might and attacked New Sweden directly, annexing it into the Dutch colony in 1655.

Perhaps the most interesting aspects of this historical period is that the relationship between the two European colonies and the native Lenape was not skewed in the sense that we are used to. In this episode, Native Americans vastly outnumbered European settlers in the New World, and essentially held the reigns in their hands as to whether the Dutch and Swedish projects would succeed or end in dismal failure, with the destruction of Swanendael serving as just such evidence. As such, themes that could be explored between the two groups include land settlement and purchase, Christianization, warfare, and even marriage and social relations, without dipping into the usual portrayals of the Natives as a vanishing culture– for at this time, that was simply not yet true.

Recommended Reading: Jean Soderlund, Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn

Those are three subjects that are close to my heart! Let me know what you think, or if you have any idea for a historical episode that would make for some great television episodes.

3 replies on “Episodic History: Ryan’s Picks”

Another great read. Perhaps our reps in DC should read up on Henry Clay. Good to see you back on the blog. How about a movie about a WWII private that was injured at 18 yrs old. Spending 2 years in rehab only to get married live a good life and fight for veterans rights. Patriot Thomas Wallace.

Nice job Ryan – perhaps you should check into The Man In The High Castle on Amazon Prime – an alternative history piece about WWII – a what if the Nazis and Japanese prevailed – two seasons in now awaiting the third.

Awesome. Wouldn’t it be cool if this ever worked out.