Recently I was reading a textbook’s account of the cause of the Civil War. This textbook was attempting to occupy a middle ground between the two major arguments for the Civil War’s cause: slavery (and its extension) versus states’ rights. While the states’ rights argument is definitively refuted by the primary document evidence of the secession crisis, this textbook made the claim that the issue of states’ rights was connected to the right of individuals in the states to own slaves. I decided that such a claim was worth some thoughtful debunking.

States’ rights had nothing to do with the secession crisis because Southern states and their political leaders in the White House, the Supreme Court, and Congress dominated the federal government and used its apparatus to preserve and extend slavery from the 1820s to 1860. In essence, Southern slaveholders had more reason to argue against the principle of states’ rights than for it, because each branch of the federal government had for decades defended and protected their right to buy, own, and move human beings over the objections of free states. The federal government did this through three crucial actions: the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, and the Dred Scott Decision of 1857.

From 1820 until the 1850s, Congress used a series of compromises to maintain a political balance between the sectional factions of the nation. Opposition to slavery among Northerners had been primarily based on economic and political grounds rather than moral ones. The controversy over slavery focused especially on the use of and access to western lands from the Louisiana Purchase and the land won in the Mexican-American War. Consequently, compromises such as the Missouri Compromise ensured equal access to the economic promise of the West for free-labor advocates in the North while also setting aside land for slavery’s expansion. This delicate balance crumbled in the 1850s, however, when Congress, the president, and the Supreme Court made a series of decisions that conclusively protected and aided slavery in its spread into the West.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, one of five laws passed as part of the Compromise of 1850, was the first example of the federal government undermining the power of states and localities in the name of protecting slavery. Passed as an appeasement to slave states after California was admitted to the Union as a large free state with incredible economic potential, The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 empowered federal marshals to deputize any citizen, regardless of their feelings about slavery, to help in the search for a man, woman, or child seeking freedom from bondage. Any citizen impressed into such a service did not have the right to refuse. Moreover, the law also incentivized judges to rule in favor of slaveholders rather than enslaved persons. Once federal marshals or bounty hunters captured a supposed fugitive from slavery, they had to go before a judge and prove that this person was the bounty they had been sent to apprehend. Judges who ruled in favor of slaveholders—that is, affirming the captured person was a fugitive from slavery—were paid more than those who ruled that the black man, woman, or child before him was, in fact, free. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 therefore created a system wherein the federal government had increased authority and power to protect a slaveholder’s human property and undermine the efforts of states and localities opposed to slavery to help freedom seekers reach Canada or to protect free or manumitted black Americans from slave-catchers and bounty hunters. Under this new system, bounty hunters from Virginia could captured a freeborn person in upstate New York, go before a judge with fabricated evidence that this person was indeed a slave owned by someone in Virginia, and know that the law incentivized the judge to agree with their claim regardless of the facts. Consequently, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 served the economic interests of Southern slaveholders and enraged Northerners, especially in regions of fervent anti-slavery activity such as Boston and western New York.

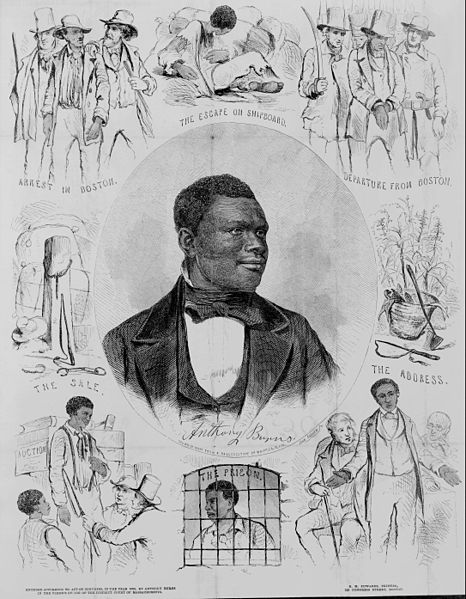

The most famous example of the Fugitive Slave Act undermining the power of a state and municipality was in 1852. Anthony Burns, an enslaved man, escaped aboard a ship and found his way to Boston. There, he was discovered by a slave-catcher sent to retrieve him and imprisoned. Enraged that a fugitive slave in Boston was set to be shipped back to the South, Bostonians raided the jail where Burns was held and freed him. While the mob was not necessarily directed by Boston officials, little was done to stop the Bostonians from giving Burns his freedom. This, however, was not the end of the affair. President Franklin Pierce, a New Hampshire Democrat, sent a contingent of marines to Boston who subsequently found Burns, captured him, and took him back into slavery under armed military escort while the residents of Boston looked on. Thus, the President used the military to forcibly return a man to slavery. No protest was elicited from the South at this event of federal government violation of the laws of Massachusetts or Boston. To Southerners, Federal authority had been exercised to defend their property as the law demanded.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 only further used federal power to defend slavery. Kansas and Nebraska were two territories from the Louisiana Purchase. According to the Missouri Compromise, these two territories were slated to become free states since they were located above the Missouri Compromise’s line that split the Louisiana Purchase into free and slave territories. In 1854, however, the Kansas-Nebraska Act effectively nullified the Missouri Compromise when it stipulated that the referendum of popular sovereignty would determine whether Kansas and Nebraska were free or slave states. Immediately, thousands of settlers flooded into Kansas ahead of the referendum and started fighting a bloody partisan conflict with atrocities committed by forces from both sides. When the referendum was held, “border ruffians” from Missouri flooded into Kansas and illegally participated in the vote. This led to a skewed result in favor of slavery. In Lecompton, Kansas, a provisional slave-state government was created and its representatives sent a pro-slavery constitution to President Buchanan for approval. Despite evidence that the Lecompton Constitution, and the vote that gave it is credibility, were fraudulent, Buchanan approved it and sent it to Congress. Rather than being the fair arbiter of a hotly-contested (and bloody) election in Kansas, President Buchanan chose not to send federal troops to maintain peace in the territory, instead agreeing to support the illegal and mendacious pro-slavery government.

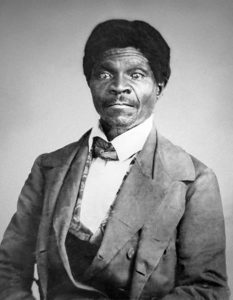

Finally, the Supreme Court handed slaveholders their biggest victory in the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court decision. Dred Scott was an enslaved man owned by an officer in the US army. During his master’s military service, Scott moved first to Illinois and then to Wisconsin, a free state and a free territory, respectively, where state laws and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 made slavery illegal. When his owner tried to move Scott away from his free-born wife in Wisconsin, Scott sued for his freedom. He argued that his owner had broken the law by bringing him, and therefore the institution of slavery, into Wisconsin and Illinois. Scott argued that slavery’s illegality in these places gave him his freedom when he and his master crossed state lines. This argument is an example of states’ rights at work: it is predicated on the idea that a state’s laws against slavery supercede the rights of a slaveholder to bring his or her human property wherever they wish. The Supreme Court, however, did not decide in favor of Scott and instead delivered a sweeping ruling in favor of federal power and the rights of slaveholders. Chief Justice Roger Taney not only denied Scott his freedom, but also ruled that black Americans, as persons designed to be perpetual property, had no right to citizenship or to sue in federal courts. Taney then went on to state that it was unconstitutional for states and territories to prohibit the spread of slavery. With a stroke of his pen, Taney erased four decades of political compromises, ruled that no state could be considered a free state where slavery was prohibited, and that slaveholders had the right to bring and settle their human property wherever they pleased. This ruling undermined any attempts by the states to limit the travel of slaves across their boundaries and also made the Republican Party’s emerging platform of limiting slavery’s spread into the territories non-existent. The decision was a major setback for anti-slavery forces and threatened the economic and political ideologies of many free-labor advocates in the North. Now, small farmers everywhere had to face the reality that they could and would be in direct local competition against slaveholders no matter where they went in the United States.

These three events—the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the Dred Scott v. Sandford ruling—show how each branch of the federal government used its authority to protect and extend slavery in the United States prior to the Civil War. Slaveholders had little incentive to support states’ rights as an idea, because doing so would give political clout to the cause of Bostonians turning a blind eye to the freedom of Anthony Burns, Rochesterians smuggling men and women to freedom in Canada, or Dred Scott using local laws to sue for freedom. Rather, slaveholders had a vested interest in maintaining and promoting the power of the federal government because it consistently ruled in their favor. Take a further look into the 1840s and the annexation of Texas and the Mexican-American War also seem to align more with pro-slavery interests than those of America in general. Jump back even further and the Three-Fifths Compromise reads more as an appeasement to the slave societies of the Chesapeake and Carolinas than any real compromise. Consequently, Southerners did not secede to defend a state’s right to own slaves. Rather, they seceded in order to create a political system that took the explicit next step and defended slavery as the integral political, social, and economic institution of their new nation, conceived in inequality and dedicated to the proposition that some men were born to be property forever.