In May of 2019, economic historians Shari Eli, Trevon D. Logan, and Boriana Miloucheva published a working paper with the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) titled “Physician Bias and Racial Disparities in Health: Evidence from Veterans’ Pensions.” COVID-19 and George Floyd were a year away, and the paper came and went without any major fanfare.

In their paper, the authors explore racial inequalities in the Union veteran pension system. Rather surprisingly, the pension system as written by law was race neutral. Originally conceived in the summer of 1862, the system was designed before African Americans could enlist in the Union Army. As Black soldiers filled the Union ranks in the following years, this race-neutral policy was not revisited. Even as Black soldiers fought in segregated United States Colored Troops units and were paid inferior wages and were ineligible for other forms of compensation, when Black soldiers were wounded or otherwise became infirm as a result of their service, they were entitled to the same pension payments as their white counterparts, commensurate on the severity of the injury.

It’s not entirely clear whether the policymakers behind the Union pension system were determined to create a race-neutral safety net for Black and white soldiers alike; it’s possible a system created before there were meaningful numbers of nonwhite men in the ranks was just never updated to incorporate the reactionary racial views that would define inequities in soldier wages and amenities. Whether intentional or not, the pension system was revolutionary in its racial egalitarianism, at least on paper. In practice, the pension system became one of the first postwar contributors to the racial wealth gap and public health inequalities that have become a focal point of the COVID-19 pandemic today.

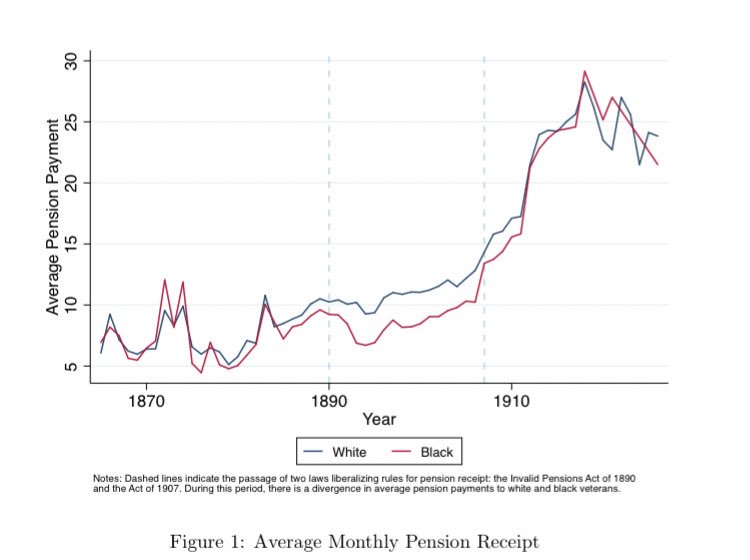

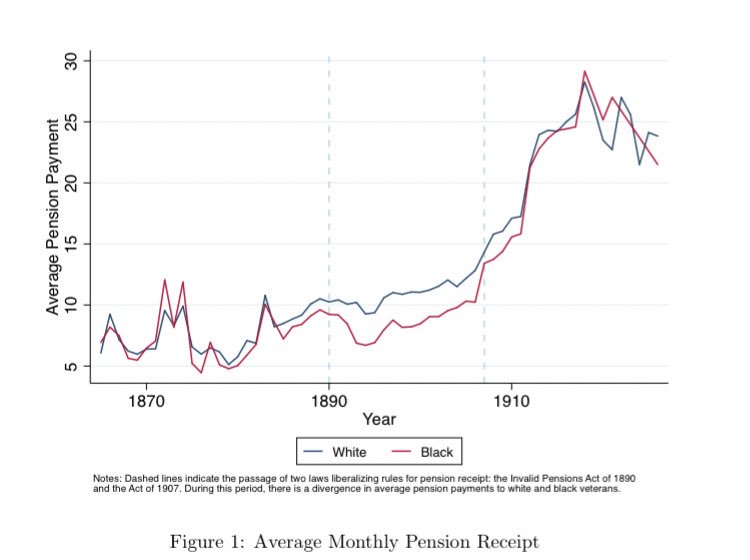

The pension system for Union veterans went through three distinct phases. First, from 1862 until 1890, pensions were limited to veterans who faced disabilities due to the war. The Invalid Pensions Act of 1890 amended eligibility to include any disabilities a veteran faced, even if they were not related to their war experience. Finally, in 1907 Congress amended eligibility a second and final time to allow any Union veteran aged 62 or older who served at least 90 days during the war and was honorably discharged from service to receive a pension, even if they did not face any disability.

While ostensibly race-blind during each phase, Black veterans faced disproportionate barriers to receiving their entitlements at every step. During all three phases, soldiers and veterans had to apply for pensions and needed to show proof of their service as part of the application. Verifying their service usually involved matching their name against enlistment rolls. This became a unique challenge for many formerly enslaved soldiers. Escaped slaves often enlisted under false names for fear of re-enslavement but reverted to their given names after emancipation. Others enlisted using their former owner’s last name, but in the postwar years adopted different last names in order to distance themselves and their identities from their traumatic lives under slavery. Far more likely to be illiterate than white soldiers due to laws forbidding teaching enslaved individuals to read and disparities in education where such laws (or slavery) did not exist, Black soldiers often could not correct misspellings or misunderstandings on the part of enlistment officers and clerks.

However, misspellings and changed names were common in the mid-nineteenth century, even among white veterans. A bureaucracy so rigid as to deny the pension of soldier Jon Freeman because he enlisted as John Freedman would have prevented untold scores of soldiers, white and Black, from receiving their benefits. In the case of discrepancies, pension clerks therefore requested written affidavits from applicants’ communities in order to verify service. Many Black friends and family members obliged, and affidavits poured into the Pension Bureau.

Pension clerks, however, often found these affidavits suspect, further requesting that applicants seek out more reliable sources. Black veterans could read between the lines then as now, and knew that this usually meant finding a white person to vouch for them, and likely one of prominent status to best secure their case. This often left Black veterans with two options to attest to their service: their white officers (many of which were either difficult to reach or were otherwise unsympathetic) or their former enslavers, who were almost guaranteed to be unsympathetic.

Even when Black veterans could prove their military service, they faced discrimination in proving disability during the first two phases of pension allotment. After the federal Pension Bureau received their applications and validated their service, it would assign each veteran a doctor to examine the applicant and verify that the injury matched the pension application and (during the first phase) that it was likely caused as a result of wartime service. As with the bureaucrats at the Pension Bureau, these examining surgeons introduced a layer of discretion that challenged the race-neutral construction of the pension system.

The most common reason for Black veterans to have their pension applications denied or pension allotments reduced compared to white veterans with the same afflictions was the examining surgeon’s certificate. Black veterans were more than fifteen times more likely to be described by their examining surgeons as “ignorant” and six times more likely to be noted as being “stupid.” These terms were not relevant to a physical examination, but nevertheless found their way into physicians’ examination notes. They also show many white doctors’ views of their Black patients. Moreover, after the 1890 reform, when the discretion of the physician became even more important in determining pension allotments, the patient’s race was mentioned specifically and regularly, despite being irrelevant to diagnosis or eligibility according to the law. According to the NBER study, prior to 1890, race was never mentioned.

During the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, the American medical community held many misconceptions about Black health. Chief among these was a belief that Black Americans were more impervious to tropical diseases, pain, and other maladies. Examining surgeons routinely downplayed Black veterans’ conditions based on this belief. When Black patients protested, they were discounted on account of their “ignorance.” Pension allotments were tied to the severity of the injury. When physicians downplayed Black suffering, they also reduced if not eliminated their pension allotment. The period between 1890 and 1910 (phase two of veteran pensions) saw the greatest level of physician discretion. Likewise, this period saw the largest gap in monthly pension allotments between Black and white veterans.

Black veterans faced one last institutional hurdle to gaining their pensions during the first phase of the pension system. Even if Black veterans cleared the paperwork hurdles and were examined by a doctor who verified their injuries, their applications were finally cross-referenced against wartime hospital records. During the war, Black soldiers did not enjoy the same access to hospitals as white soldiers. When they were admitted, they were treated in segregated hospital wards that regularly lacked food, sanitation, and—most notably for the purposes of this post—reliable records. Having survived the war despite being treated in shoddy hospitals if treated at all, Black veterans now found themselves denied pensions for their injuries due to the initial disparities in healthcare access during their service.

These barriers stacked up, even if most Black veteran pension applicants were still able to successfully garner their pensions. According to the 2019 NBER study, 75.4% of Black veteran pension applicants received their pensions. However, this was downright anemic compared to the 92.6% white veteran success rate. Moreover, Black veterans received an average monthly pension of $7.89 while their white counterparts received $11.01 on average. It bears repeating that there was no legal discrimination in pension allotments, nor were there adjustments based on cost of living differences. These racial discrepancies can be attributed almost entirely to the systemic barriers Black applicants faced outside the framework of the law.

Pension allotments no doubt contributed to the racial wealth gap among Civil War veterans. Not only had Black soldiers been paid less during war, they received less of a pension despite there being no legal discrimination in pension policy. Moreover, the NBER study showed that higher pension allotments (when controlled for disease or injury severity and race) resulted in higher life expectancies, to the tune of an additional 0.18 to 0.42 years of life per extra dollar of pension allotted per month. Black veterans’ experiences both in wartime hospitals and in pension examinations after the war also contributed to a growing mistrust in the medical field (further confirmed by incidents like the Tuskegee syphilis study), compounding inequities in care and access.

The story of pension discrepancies is far from the zenith of public health inequality in American history. Black Americans suffered from a lack of access and inferior care long before the Civil War and long after the last Black Civil War veterans died. Nor were pension disparities the leading cause of the burgeoning racial wealth gap or even the foremost contributor to elevated levels of mortality among Black Americans in the decades after the Civil War. But Black veterans’ pensions demonstrate how a race-neutral policy can be hamstrung by systemic oppression with outsized consequences and how that experience can contribute to mistrust of the medical community. Civil War pensions are therefore a historical microcosm of America’s racial public health inequity crisis.

Further Reading

Eli, Shari, Trevon D. Logan, and Boriana Miloucheva. “Physician Bias and Racial Disparities in Health: Evidence from Veterans’ Pensions.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, May 2019.

Shaffer, Donald R. After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Shaffer, Donald R. “‘I Do Not Suppose That Uncle Sam Looks at the Skin’: African Americans and the Civil War Pension System, 1865-1934.” Civil War History 46, no. 2 (June 2000): pp. 132-147.

Kretz, Dale. “Pensions and Protest: Former Slaves and the Reconstructed State of America.” Journal of the Civil War Era 7, no. 3 (September 2017): pp. 425-445.