In just a few days, July 21 will see the premier of the much-anticipated movie Dunkirk, which tells the story of the World War II battle of the same name in which British and French forces were evacuated across the English Channel by civilian watercraft under the guns of the Third Reich. When done well, all of us here at Concerning History love seeing history on both the big and small screens, as it seems to bring the past to life with a vibrancy and immediacy lacking in other media and to powerfully shape public perception and memory of events. The number of history-related series on television and streaming services has blossomed in recent years, but we all have our special interests and can’t help but pine for the opportunity for some of our pet topics to get the attention we know they deserve. In what we hope will become a long-running series, I’ve decided to pull together this list of a few historical events and periods I feel would make for highly compelling or even necessary television. While I’m sure we’ll eventually do the same for movies, the long-running and episodic format of TV series lends itself much easier to this sort of historical adaption, giving the story more time to play out while paying attention to accuracy in material culture and setting as well as the historical record. My purpose here is not so much to educate on what I’m talking about; rather, I hope to tell just enough of an intriguing story to pique your interest, drive you to find out more, and picture for yourself how awesome that story might look on the screen. Towards that end, I’ve included some suggested reading for each idea that serves as a perfect gateway to learning more on the subject. Enjoy!

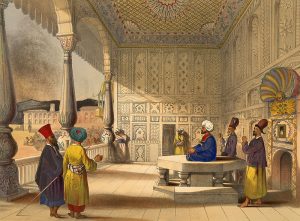

The First Anglo-Afghan War — The breadth of the British Empire in the nineteenth century is such that it has often been compared to someone with painful gout, bellowing in agony anytime it is so much as lightly poked. Nowhere is this more evident than in India, the crown jewel of the empire and the sum of all its fears. Russian expansion eastward into Central and East Asia provokes frenzied British focus on securing India’s northwestern frontier: Afghanistan. A high stakes contest of state-craft and espionage between British and Russian agents for the favor of Afghanistan and nearby Persia ensues, which Rudyard Kipling later calls “The Great Game.” When the rightful ruler of Afghanistan, Shah Shuja of the line of Timur, is dethroned and exiled in the wake of a popular uprising, it is to Britain he turns for sanctuary and revenge; all too happy to make safe the frontier once and for all, Britain and her East India Company oblige. The war that follows, fought from 1839 to 1842, will see legions of native Indian sepoys (Company soldiers) be led into unfamiliar and harsh terrain by white officers of widely-varying competence. Tired of living under a corrupt tyrant, the impassioned tribes of Afghanistan will meet them by the thousands, led by the charismatic new emir, Dost Mohammad Khan. There are victories and defeats on both sides and atrocities abound. Not only would these events make for a riveting series, but they also offer one of the best opportunities for a balanced treatment of imperial history. Themes of European triumphalism or martyrdom always lurk around these topics, yet the Great Game offered significant agency to native regimes and their subjects as they attempted to play imperial powers off against each other; likewise, the war itself saw non-European irregular warriors ultimately drive off the disciplined might of Britain. Its relevance to twenty-first century events, too, can hardly be understated.

Recommended Reading: William Dalrymple, Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839-42.

The Atlantic Slave Trade — This is my plea for the show I had hoped Taboo would be. As a matter of rote, we are taught in school how wretched the Atlantic slave trade was, but rarely do its horrors ever actually pass beyond words and statistics. The 2013 film 12 Years a Slave eloquently and disturbingly translated the brutality of nineteenth-century slavery in America to the screen, but did not do so with the trade itself. The human misery of the trade can scarce be conceived. African societies viciously tore themselves apart as previously small-scale systems of raiding and bondage were industrialized to feed the European demand. Packed into cramped cargo holds, mal- or undernourished, sick, and abused, Africans perished by the hundreds on each ship as they were ripped from their homelands. Though exponentially smaller in number, the relative proportion of white crew who would die on these journeys was higher than even African mortality in the hold below. The dead of both looked forward only to being heaved over the side. It would only be effectively outlawed in 1807, centuries after its beginnings. We have now reached a maturity in television, both in story and in visual content, that would allow for a properly graphic portrayal of the trade, one that pulls no punches in its visceral, gut-wrenching, horrifying nature. The show could follow an existing historical narrative, such as that of Little Ephraim and Ancona Robin Robin John, two princes of the African city of Calabar that were captured, bought, and sold around the Atlantic Rim until finally finding their freedom in London. A fictional story could serve equally as well, as long as pains were taken to make it representative. The series I describe is not an enjoyable one in any conventional sense of the word. Indeed, if done correctly, it is not something I would ever want to watch a second time. Yet I fervently believe such a show is not only desirable but necessary if we are ever to conceive of this great tragedy as something more than a distant, sorrowful statistic.

Recommended Reading: Randy Sparks, Two Princes of Calabar: An Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Odyssey

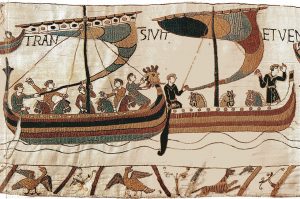

1066 and the House of Godwin — Ever since Game of Thrones found astonishingly wide popularity, conniving medieval politics has been in vogue. Most shows that feature these dark and cunning atmospheres are set in the late or High Middle Ages, however, or a world very much resembling these settings. As important and tangled as, say, the ever-popular War of the Roses is, I propose a series on an even more fundamental period in English history, and one shockingly bereft of adaptations: the Norman Conquest. In the beginning of the eleventh century, the kingdom united by Wessex has fallen to the Danes, its rightful heirs fled for sanctuary in Frankia. The Saxon king Edward, later known as The Confessor, is finally restored to his throne and Danish rule ended, but Edward is a disinterested ruler and too fond of his Norman companions from exile. Godwin, his most powerful lord and right hand, resolves to action. For the first time in a very long tradition, English nobles rise up against the king, asserting their rights under the crown. The House of Godwin is forced into exile, but its patriarch is more charismatic and beloved than Edward and has no trouble raising an army upon his return. Godwin forces Edward to back down, and is restored to his earldom. Years later, Godwin’s son Harold has replaced his father as Edward’s right hand, and upon Edward’s death is chosen as king by the witan (Saxon noble council which confirms royal authority). One of Edward’s Norman favorites, the bastard Duke William, objects, claiming Edward named him as successor and preparing to invade. As Harold prepares to meet the threat, England’s old Scandinavian enemy rears its head, landing an invasion fleet in the north led by the Norse king Harald Hardrada and Harold’s own brother, Tostig, formerly exiled for cruelty by Harold himself. In a lightning campaign, Harold is able to eliminate the northern threat and return south, but William has crossed the channel, and it is on the fields of Hastings that the fate of England will be decided.

Recommended Reading: David Howarth, 1066: The Year of the Conquest.

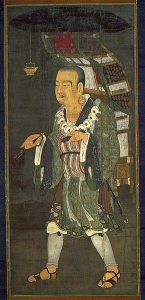

The Travels of Xuanzang — This idea is quite a bit different from the others I propose here, but no less interesting. Xuanzang was a Chinese Buddhist monk of the seventh century AD. Concerned that the Buddhist texts and teachings transmitted to China through cultural contact were incomplete or misinterpreted and seeking to rectify these mistakes and restore a more pure Buddhism to China, Xuanzang set out for India in violation of the Tang emperor’s prohibition on foreign travel. Xuanzang’s journey would take seventeen years, leaving China by the northwestern Gansu corridor, circling down around the Hindu Kush, and finally reaching India. Captured and fortuitously released multiple times, Xuanzang would encounter brigands, Turkish Khagans, and, at last, friendly Buddhist monks as he made his way to the birthplace of the Buddha, all the while taking every opportunity to engage in scholarly debate and deliver sermons. Upon his return to China, Xuanzang was welcomed with a great procession and showered with honors; he had returned with over six hundred texts, seven stone Buddhas, and over a hundred relics. Refusing any appointments to office, Xuanzang lived out his days quietly translating his texts. His travels were meticulously documented by the Tang in their official records, which later inspired the Ming-era novel Journey to the West, a pillar of Chinese literature still today, though Western audiences might know it better as Monkey. A more fantastical retelling, not to mention almost a millennium removed from Xuanzang himself, Monkey nevertheless offers a fun opportunity for any adaptation of Xuanzang’s life to the screen, as references and inspirations for the events of the later novel can be inserted into a grounded adventure of exploration and self-discovery. One disclaimer, however (knowing Hollywood): historically-accurate casting only, please. Xuanzang should not be meeting any white people on his journey through seventh-century China, Kyrgyzstan, Persia, Afghanistan, and India.

Recommended Reading: John Keay, China: A History; Wu Cheng’en, Monkey, Arthur Wales, translator.

Late Bronze Age Collapse — There have been two great civilizational reset buttons in western history, periods filled with violent upheaval and structural collapse, made all the more intriguing by the sudden dearth of written sources to help shed light on events. The fall and retraction of Rome is the most well known of these two, but much the more cataclysmic was that which occurred at the end of the Bronze Age. During the Late Bronze Age, the eastern Mediterranean world had entered a golden age. Maritime trade had begun to flourish along the coastline, and the mighty Egyptian, Hittite, and Babylonian empires regularly composed courtly letters to each other and the minor regional states, addressed to “My brother,” even as they relentlessly jockeyed for territory and influence. Having thrown off the yoke of the Minoans, Mycenaean city-states on the Greek mainland constructed colossal citadels and started to spread outward. Magnificent works of art and architecture abounded, while imperious warriors clad in bronze piloted their highly-technical chariots to victory. All this would come crashing down around the year 1200 BC. Suddenly, states began to unravel. Panicked letters telling of raiders and invaders appeared, and then silence. The archaeological record shows that every major city and settlement in Greece, Anatolia, and the Levant was violently destroyed; few were ever resettled. Only Egypt survived, though not unscathed: two massive battles took place in defense of the Egyptian heartland against hordes of invaders known as the “Sea Peoples,” and the empire entered a slow decline. Even more intriguingly, Egyptian reliefs of the battles with the Sea Peoples show women, children, and ox carts laden with goods alongside their warriors; were these invaders, or displaced peoples seeking a new homeland? The cause of the collapse, or a symptom? So great was the structural trauma of these events that the Greeks lost their literacy. When they later regained writing, they made use of a completely different, borrowed, script. The memories of this period remain with us today. Centuries later, they would be expressed through such foundational literary works as the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the biblical book of Exodus. Until recently, historians and archaeologists had no convincing idea what may have caused such utter collapse. Now, it seems increasingly likely that a series of natural disasters and famine destabilized the fragile integration of the Eastern Mediterranean. Unable to sustain their world system, civilizations imploded. The possibilities for a TV series set against this backdrop are endless. An intimate drama of individuals dealing with the death of their world; a political intrigue set at the Hittite court in central Anatolia as they deal with rebellious lords and Mycenaean encroachment into their western provinces; a tragedy of a pharaoh protecting his people from refugees protecting theirs; all could even be the same show. The constant remains an historical era that is endlessly fascinating.

Recommended Reading: Eric Cline, 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed; Eric Cline, Gary Beckman, & Trevor Bryce, The Ahhiyawa Texts

So there are my picks! I can only hope that in this brief space I’ve been able to convince you of how awesome these subjects would look fully realized on television. Don’t hesitate to offer suggestions of your own below. We will certainly have many more installments in this series, so some of your own favorites not mentioned here may very well get the attention they deserve in a future post.

One reply on “Episodic History: Bryan’s Picks”

Shut up and take my money!