The great modern European empires we read about in our history books are gone. British, French, German, Italian, and Russian imperial ambitions all collapsed, in turn, over the various disasters which befell their empires during the course of the twentieth century, suffering from two world wars, occupations, revolutions, and the ever-blowing, seemingly inevitable winds of change. All, however, live on in states of global renown today: though their empires have been lost, the core of their home territories remain influential players on the world stage (in many cases, still adjusting to the realities of their diminished power). Even the Ottoman Empire lives on in a certain way, in the modern state of Turkey.

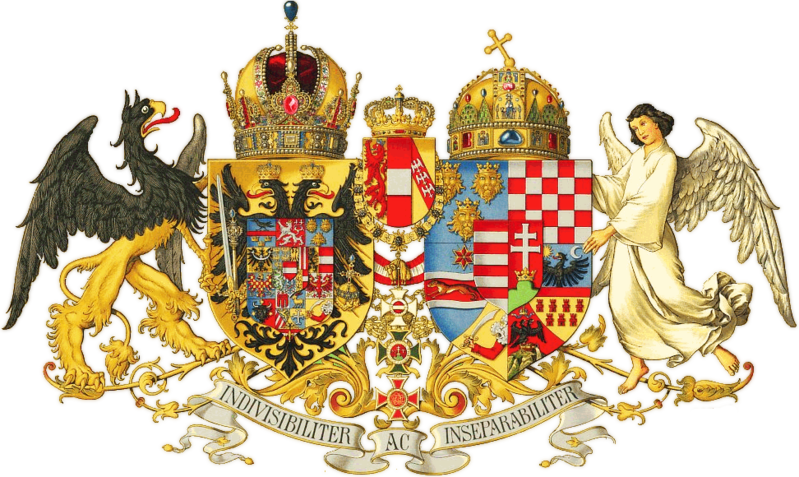

Running down that list, I’ve covered the primary European belligerents of the First World War— or perhaps even more importantly, the majority of the playable nations in the board game Diplomacy, a true standard of imperial standing—save, that is, for one. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy, the Austrian Empire, and the Habsburg Monarchy: all names for the same unusual and now long-gone entity. Who among us can say that Austria remains a major global influence among European nations today? Its former constituent parts, from Hungary to the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and much of the (likewise) former Yugoslavia have not fared much better. Unlike all the above mentioned empires, the Habsburg realm is well and truly gone, the dynasty throneless, and former empire completely splintered.

This is, in part, because the Austrian Empire had almost no business existing at all—least of all for as long as it went on. Throughout its hundreds of years upon the European political stage, the Habsburg realm extended over no natural geographic, cultural, or linguistic portion of the map. Instead, it consisted of a patchwork quilt of Danubian territories of different cultures and languages stapled together by a medieval dynasty with a remarkable talent for beneficial dynastic marriages, frequently preserved thanks to a propensity for inbreeding. The core of Austria itself originally did not represent a significant cultural division from what would become Germany, and up until the end of the Second World War, pan-German nationalists advocated for a unification of Germany and Austria. Austria’s independence then and today are primarily a product of its happenstance acquisition of significant non-German imperial territories, creating the idea of an Austria that was separate from the rest of Germany, despite their shared language, culture, and history.

Next month, on November 11th, we will observe the 99th anniversary of the armistice between the Allied Powers of the First World War and Germany. On that same day, Emperor Charles I issued his de facto abdication from his Empire’s thrones, making official the dissolution of the Habsburg realm that had already begun to splinter in the war’s final days. In his memoir The World of Yesterday, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig reflected dourly upon the independence of the resulting Republic of Austria. He had this to say, after recalling the economic ruin of the state, whose financial and industrial infrastructure had not been built to stand on its own:

A country forced to be independent when it bitterly rejected the whole idea. Austria wanted either to be reunited with its old neighbour states, or to unite with Germany, whose people were of the same origin. It did not want to be reduced to the humiliating condition of beggary in its new truncated form. The neighbor states, however, were not anxious for any economic alliance with Austria as it now was, partly because it was so poverty-stricken, partly for fear that the Habsburgs might return. Meanwhile, the Allies would not hear of a union with Germany in case that strengthened their defeated German enemy. So it was decreed that the German-Austrian Republic must stay as it was. A country that did not want to exist was told–for the first time in the course of history!–that it must.

Despite the great odds observed by Zweig, the Austrian state has endured and prospered into the modern day, the dreams of a reconstituted Habsburg Empire and of unification with Germany buried—even with the second briefly achieved, but under horrific conditions in the Anschluss of 1938. Thus, the idea of Austria as an imperial power, or even a European superpower of any kind, is fully resigned to Zweig’s titular world of yesterday. This distinctly past-tense view of the Austrian Empire is only augmented by the idea of them as the empire that shouldn’t-have-been, a distinctly medieval construct in a modernizing world that. After the Habsburg dynasty’s high-point in the seventeenth century, the Empire’s history is, in large part, a story of attempting to keep their patchwork Empire together in the face of other nations, such as Germany and France, and against modernizing political thought that would render the dynastic realm obsolete. Though their performance in Europe’s wars in the 18th and 19th century was uneven at best, the Habsburgs largely managed to hold their realm together with surprisingly flexibility, muddling along into modern times despite their anachronisms. As the 19th century Austrian Prime Minister Eduard Taaffe proclaimed, Austria’s policy could be described as “fortwursteln,” a German word roughly translated as a combination of the thoughts “keep improvising,” “keep slogging on,’ and “keep clowning,” according to the historian Frederic Morton.

For me, it is the anachronisms and contradictions of the Habsburgs’ realm that makes Austrian history so fascinating—especially how the Empire tried to muddle onwards in the face of them. One of my favorite “what-if” questions in history is what would have become of Austria-Hungary had they not been so decisively defeated in the First World War, which became the primary catalyst for the Empire’s collapse. At the dawn of the 20th century, after all, democratic suffrage continued to expand within the realms of the Dual Monarchy, and political thinkers—such as the assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand — considered ways in which to re-arrange internal political divisions in order to facilitate greater stability.

Though the Habsburg Empire is now nearly a hundred years gone, I believe that there are still a number of lessons, both political and social, to take away from them. In my next post here, I hope to delve into the writings of Zweig and Morton a bit more deeply as I try to tackle themes relevant then that seem to be rising in their importance now, such as internationalization, ethnic diversity, modernization, and an apparent crisis of liberalism.

One reply on “The Strange Longevity and Disappearance of the Habsburgs’ Patchwork Empire”

Interesting!