The COVID-19 pandemic did a number on the film industry, with many films delaying production or, in some cases, delaying the premier of already-finished movies by a year or more as theaters emptied and moviegoers stayed at home. One such delayed movie, which we caught wind of on its second round of press and subsequent wide release on Netflix, was Radium Girls. While it first appeared to one of dozens of lower budget period pieces, Radium Girls ultimately impressed us with its nuanced portrayal of the 1920s and its decision to end on a note very different than many of these triumphal rage-against-the-machine stories.

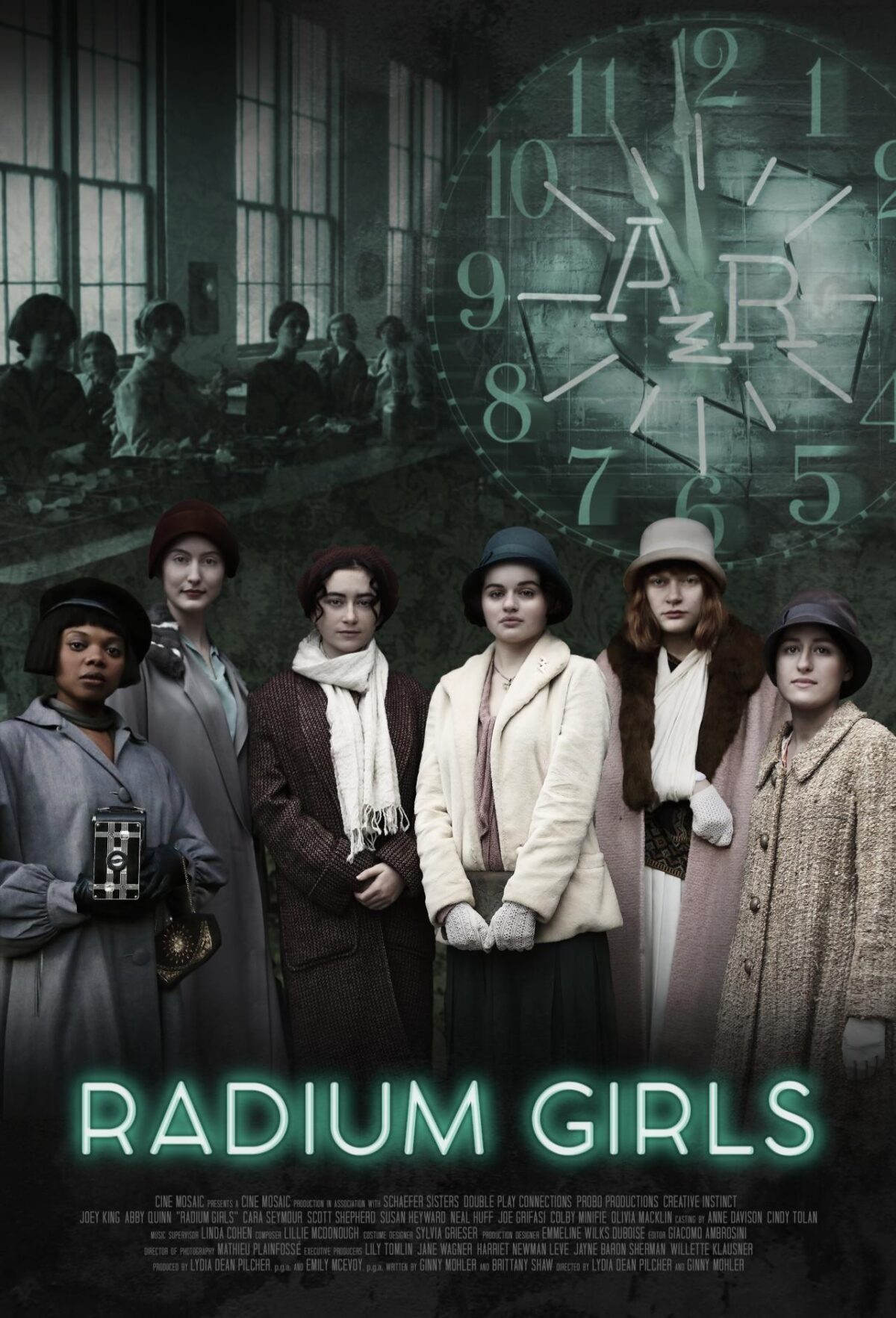

Radium Girls tells the true story of the Radium Girls, a group of young women factory workers in New Jersey who, during the 1910s and 1920s, applied the radioactive chemical radium to certain household items (most notable watches) to make them glow in the dark. Instructed to lick the tips of their already-coated paint brushes to refine their detail work, these women developed radiation poisoning in large numbers; by 1930, over 50 had fallen ill, and over a dozen had died gruesome deaths, their hair falling out and their jaws deteriorating so far that some detached completely from their skulls. The movie follows the character of Jo Cavallo, a the only Radium Girl at American Radium’s New Jersey factory that does not lick her paint brushes. Her two sisters, however, do, resulting in one’s premature death before the events of the film and the other’s increasing debilitation. Encouraged by newfound socially conscious friends as well as labor leaders who inform her of other cases, Jo leads five other women in suing American Radium for compensation after they have knowingly endangered legions of women.

Unlike other stories of this sort, however, Jo’s fight does not have a triumphant, fist-pumping ending. The ensuing case turns ugly like only a lawsuit against a corporation can, with the women’s reputation being maligned by the counter-argument that they just have syphilis (a diagnosis provided by a man who isn’t even a medical doctor). The only witnesses willing to back up the girls’ story are either silenced or rendered inadmissible by a justice system all too willing to cooperate with those in power, and even the Radium Girls’ ultimate settlement is negotiated by a Federal judge who holds stock in American Radium. The machine is too powerful to keep fighting, no matter how much Jo wants to try; her compatriots simply accept more money than they’ve ever dreamed of seeing, American Radium undergoes performative, but ultimately meaningless, penance, and nothing significant really changes. We’ve seldom seen more melancholy commentary on the state of American corporate justice, especially in the wake of the recent Purdue Pharmaceuticals/Sackler family case settlements.

Aside from its core story, Radium Girls also delivers a refreshingly unique portrait of the Roaring Twenties. Rather than taking in place in New York or Chicago or another metropolis, the lives of Jo and her friends proceed in relatively suburban New Jersey, showing how the culture and fashions of the twenties were not just confined to the glitz and glamour of the big city. Undercurrents of youthful disobedience and social activism (on which Kevin wrote his masters dissertation) can be seen through Jo’s paramour and friends, one of which is a survivor of the Tulsa race massacre and a self-proclaimed communist. This group’s New Year’s Eve party is at one point brutally broken up by police, further demonstrating how differently American society and the powerful have interpreted the freedoms guaranteed under the Constitution in different eras. Even the setting of this kind of story in this decade is unique; most American education leaves the history of labor relations and predatory corporations behind around the year 1900, but it has never stopped being a struggle.

For all its surprising merits, Radium Girls still lacks some of the production value of other, higher budget, period pieces. We appreciated their impulse to use actual footage from the 1920s in the film, but their actual usage was disjointed, jarring, and at times approaching nonsensical. Despite this, if you enjoy 20th century period dramas, or want to draw strength from the long line of women fighting the good fight in this country, this film certainly deserves a place on your list.