With only two days left in 2019, it’s time for our annual retrospective on the year. This time, as there are also only two days left in the decade*, we wanted to cast our eyes to a larger horizon and discuss what historical moments and themes the 2010s as a whole will be remembered for. There are others that deserve mention, including the rise of illiberal democracies, economic nationalism, and more, so we invite you to add your own in the comments below.

Bryan: I believe that this past decade will be remembered in large part as the decade that climate change became not only undeniable, but undeniably present. As we have noted in some of our previous end-of-year posts, hurricanes and extreme weather have spiraled out of control, particularly in the second half of the decade. Close to home for Heather and me, 2010-2019 may be seen by future generations as the years in which the state of California began to become unlivable. Rampant wildfires throughout the state have only gotten more frequent and more fierce, with the worst in state history coming in the fall of 2017, only to be superceded by another fire a year later. Unwilling or unable to completely fire-proof California’s infrastructure, some power companies have announced that they will be conducting planned outages when fire conditions reach dangerously high levels, and may need to continue doing so for the next ten years. In only their first year of implementation, these planned outages have affected tens of millions of people, including yours truly. Even with these precautions, Northern California was once again wracked with a fire likely begun by powerlines. As California’s homeless crisis also escalates, more and more people are driven into the path of future fires as they seek areas with affordable housing prices. Combined with the mudslides and flooding that occurs when these ruined landscapes are subjected to California’s rainy season immediately thereafter, not mention the state’s ever-present seismic activity, the Golden State may not be golden much longer.

Kevin: In addition to the environmental damage wrought, the impact of climate change is finally being seen politically, especially in the manifestation of an international grassroots movement led in large part by young people. This isn’t the only domain where we’re seeing a surge of youth activism. Towards the end of a decade of mass shootings, the Parkland survivors’ March for Our Lives movement sparked what felt like the first change in the gun control debate since Sandy Hook. Young people are throwing apathy aside and challenging the status quo as a threat to their future. Beyond youth, the impact of #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter have reshaped the discourse of inequality in America. These movements arose from the convergence of social justice and modern technology that have resulted in them manifesting IRL in new ways. Why now? Like climate change, these are long-standing issues, but several catalysts in recent years (Ferguson, Donald Trump, Harvey Weinstein) have put them in front of an increasingly cynical American public. This decade may come to represent a return to levels of sustained activism not seen since the 1960s.

Jeff: Almost paradoxically, while the 2010s (and particularly the last half of the decade) seemed inundated with headlines, journalism stock tumbled. From innumerable local newspapers to national titles like Time and Newsweek, mass layoffs and closures have hollowed out much of the fourth estate in the U.S. and other liberal democracies. The causes are vast: rising costs, declining circulation, a rapidly changing business model, internet norms demanding free content. The effects are dramatic and concentrated: less capacity to hold the powerful accountable. This has and will continue to exacerbate rising climate unaccountability, corruption, authoritarianism, and other dangers. One report found that following the closure of a local newspaper, localities were more likely to experience increased local government costs and inefficiencies. While major publications like the New York Times and the Washington Post have thrived amid the increasingly turbulent national political landscape, other sources have not been as fortunate and the national discourse and safety has been and will be all the worse for it.

Ryan: In a large part, I think that decline in traditional news consumption can be associated with the dramatically changing ways in which we consume our news media. Where once distinguished newscasters and trusted papers provided much of our news, curated opinion sites filtered through the echo-chamber algorithms of Facebook have taken their place—which is my segue into a point I’ve been harping on for the previous two years.

The 2010s, as I see it, has been the height of the wild west of the Internet, now slouching towards decline. In its most ideal form, the internet was intended to be a discovery tool, putting the world’s information within the reach of anyone with a connection. In this sense, it could be an equalizing force, breaking down barriers and costs of access to traditional sources. Social media – one of the internet’s most popular children – had the similarly idealistic goal of connecting people across barriers, enabling closer communication and sharing.

However, social media has since become dominated by business interests, both of their creators and sponsors, manipulating what content is seen and by whom, plagued by data and privacy scandals, and now on the forefront of the political espionage. The boom of Fake News has been made possible due to the ease of internet access and sharing power of social media, which has serviced to dramatically undermine public trust in news and one-another. Internet access itself is under siege from world governments seeking to control what is seen, as well as corporate internet providers eroding regulations that prevent them from throttling access indiscriminately.

The internet, of course, is not going anywhere in the coming decades. But its idealistic sheen seems to be fading fast—if there was a decade during which its greatest promises could have been fulfilled, we have passed it. Moving forward, the internet of the future seems far more likely to be just as fragmented and controlled as all other forms of media.

And don’t even get me started on the re-invention of cable television through the rapid rise of more and more streaming services, or the all-consuming rise of Amazon. There’s a lot to be said here— including the more optimistic side of the increasing awareness the public has for issues of digital privacy, access to information, and so forth. But I think I’ve already considered more than enough for now!

Heather: To jump off Ryan’s wider point about the evolving and expanding role of the internet in our lives, I’d like to highlight perhaps the most iconic online wave of the 2010s: the rise of influencer culture. Social media influencers (SMIs) have inspired delight and derision in equal measure. Their omnipresence marks a distinctive new chapter in international marketing. What might be called the internet’s peculiar institution has roots nearly as old as the internet itself, of course. As early as the 1990s, academia was keeping tabs on “Virtual Communities of Consumption.” Indeed, one could even argue that influencers are simply the modern answer to celebrity endorsements, a practice that has been around for as long as celebrities have. Despite these historic roots, however, influencer culture in its current form is undeniably a phenomenon of the 2010s.

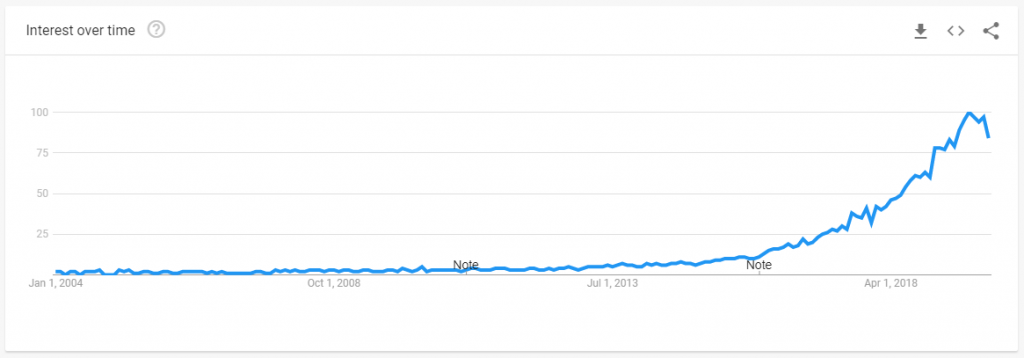

By the end of 2020, SMI culture will have turned 10 years old and changed the face of marketing. SMI marketing is easily recognized and separated from other more traditional forms of marketing in both its methods and aesthetics. It is accomplished by thousands of online cults of personality. It is defined by gimmicky glossiness, corporate sponsorship, and, almost without exception, youth and beauty. Most importantly, it has taken the world by storm. A Google Trends chart plotting the degree of worldwide internet interest in the term “influencer” from 2004 to December 29, 2019 shows exponential growth corresponding perfectly with the progress of the current decade. Even the internet unsavvy will recognize some of SMI culture’s defining moments: Kony 2012, the Ice Bucket Challenge of 2014, the 2017 Fyre Festival… The list goes on. What was initially a purely online phenomenon has since exploded onto the IRL scene, yielding fan conferences, merchandise, book deals, podcasts, and more. As the decade comes to a close, though, some weighty questions loom: how long can SMI culture survive, and what mutations will it perform to maintain power in an ever-evolving online landscape?

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading and engaging with us, and we hope you have a wonderful new year.

-The Concerning History Staff

*We acknowledge that while there is some dispute as to whether 2019 or 2020 is actually the last year of the current decade, decades are more useful as as historical constructs rather than discrete and specific periods of time. As most people are treating this week as the end of the decade, so too shall we.

Further reading about SMI culture

Bakshy, Eytan et al. “Everyone’s an Influencer: Quantifying Influence on Twitter.” WSDM’11 (February 9-12, 2011): 65–74

Freberg, Karen. “Who Are the Social Media Influencers? A Study of Public Perceptions of Personality.” Public Relations Review 37, no. 1 (2011): 90–92.

Kozinets, Robert V. “‘E-Tribalized Marketing?: The Strategic Implications of Virtual Communities of Consumption.’” European Management Journal 17, no. 3 (1999): 252–64.

Zhang, Yifeng. “Identifying Influencers in Online Social Networks.” International Journal of Intelligent Information Technologies 9, no. 1 (2013): 1–20.