Over the past few months, national anthems have been on my mind, for a combination of factors. The first is this wonderful video on the history of “The Star-Spangled Banner” I came across this video from Vox— if you watch it, you’ll get a preview of some of the points I’ll be hitting on in this post. The second is some research I conducted on the Russian national anthem, which has endured from Stalin’s Soviet Union to the present with only slight lyrical changes due to the message of global strength, prosperity, and purpose for Russia it presents that many Russians find deeply appealing. The third and final reason is really just current events– the forthcoming presidential primaries, and another Independence Day come and gone.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” was not explicitly written as the U.S.’s anthem, and it shows. It fits neither the mold of anthems like Russia’s “State Anthem,” bombastic and unapologetically patriotic, nor that of those such as Britain’s “God Save the Queen” or Canada’s “O, Canada,” hymn-like and reverential. Rather, its closest lyrical relative may be The Netherland’s “Wilhelmus,” in that its lyrics proceed in a story-like fashion focused on one particular subject rather than speaking much more broadly of the country at large. Musically “The Star-Spangled Banner” stands out as well, notoriously difficult to sing due to its unusually wide range of notes– not exactly a useful trait for a song intended for frequent performance.

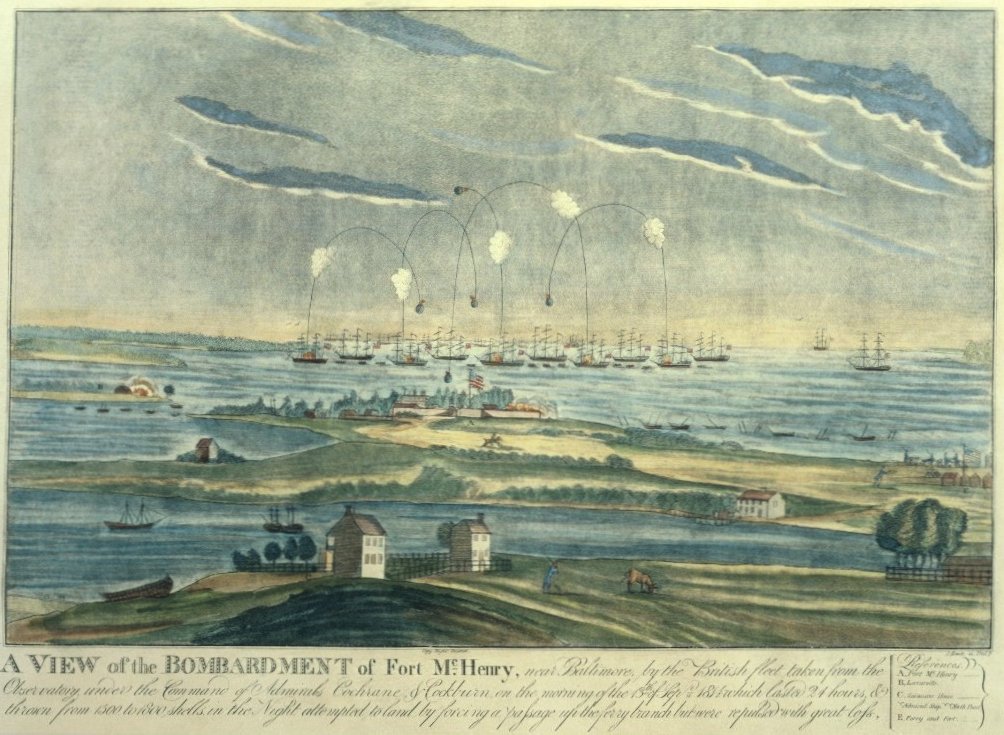

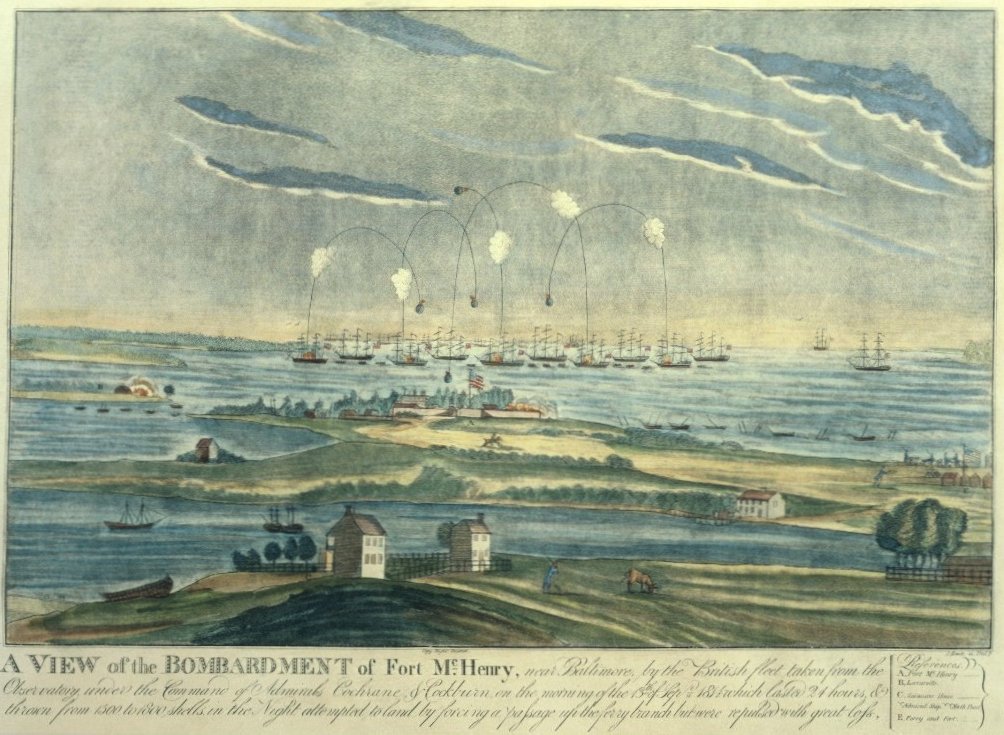

It’s an unusual song from the historical viewpoint as well. The battle referenced in its lyrics is the Battle of Baltimore during the War of 1812 which, while ending in a victory for the U.S., would be fleeting, as British forces would occupy and burn the fledgling Washington, D.C., only about one month later. It would be a stretch to call 1812 a military victory for the United States, which is likely why the only parts of it commonly remembered today are said burning and Andrew Jackson’s victory at the Battle of New Orleans. Amusingly, while that battle was decisive enough to catapult Jackson into national prominence and the presidency, it was fought and won after peace had been declared in Europe: meaning the U.S.’s greatest success of the war was fully unnecessary.

Historians have ascribed a more important legacy to the war than its military outcome, however, arguing that it played a role as the U.S.’s second war for independence. Much like the first, the endurance of the young republic was itself a victory, proving its staying power as it held firm against the British military machine for a second time. In doing so, the U.S. showed Britain and the world that its independence was no mere temporary accident and its government more than an idealistic dream. Never again would British troops invade the United States.

It’s fitting then, I think, that resilience is what the commonly sung lyrics of “The Star-Spangled Banner” honor: that through the bombs and rockets of war, the colors of the United States continued to fly, symbolizing the preservation of the republic’s ideals. The significance of this notion is rooted in the revolution itself, for though it is simple to forget in an age where proclamations of American strength, power, global influence and, dare I say, greatness are common, it has never been a historical inevitability that the United States would thrive nor endure. One of my favorite portrayals of this reality is in the 2008 HBO miniseries John Adams: when the Declaration of Independence is adopted by the Continental Congress, there is no celebration. Rather, only grim silence. Much as we now consider the War of 1812 itself, the lyrics of “The Star-Spangled Banner” suggest that victory is not gleaming heroics, but rather stalwart endurance.

This is why I have come to see the “The Star-Spangled Banner” as an extremely appropriate national anthem for the United States and one that, I believe, speaks to what is perhaps its best and most original quality. It is not a song that boasts, brags, or proclaims divine or natural superiority: instead, it is one of modest and humble resilience and of continued endurance against great trials. While proclaiming the U.S. to be the “land of the free and the home of the brave” is certainly not modest of itself, the lyrics arguably seeks to justify this claim in the preceding verses through the imagery of endurance against an invader rather than claiming virtue outright.

Humility is a virtue inherit in the foundations of American democracy as well– at least conceptually. Though the idea that no person is superior to another is enshrined in the U.S.’s Declaration of Independence, the very architects and authors of that independence failed to pursue that idea to its highest conclusion, allowing deep inequality based on race, sex, religion, nationality, and so forth, to thrive in the centuries to come. The crimes of enduring and enforced inequality are among the blackest spots on the United States’ historical record, and overcoming their legacies that remains, to borrow words from Abraham Lincoln, America’s truly “unfinished work.” It takes a modest nation and a modest people, I believe, to reflect critically upon this past and strive for continued betterment rather than accepting an imperfect present.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” recalls a near-forgotten war in a time where the nation’s “unfinished work” remained even far greater, and yet its modest emphasis on perseverance is an idea of lasting importance to the United States. Its lyrics should be a reminder that national endurance is not a given: that the United States must continue to honor and empower its ideals, and not take its own survival for granted. In the song’s context, the threat is invasion, and yet it could just as easily be one of ideas, of a complacency unwilling to conclude the nation’s “unfinished work.” The final verses of the common lyrics ask a question: “O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave; O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?” To me, the question is a lasting one: a call for re-examination, and lasting, continued work to ensure that the answer is “yes.”

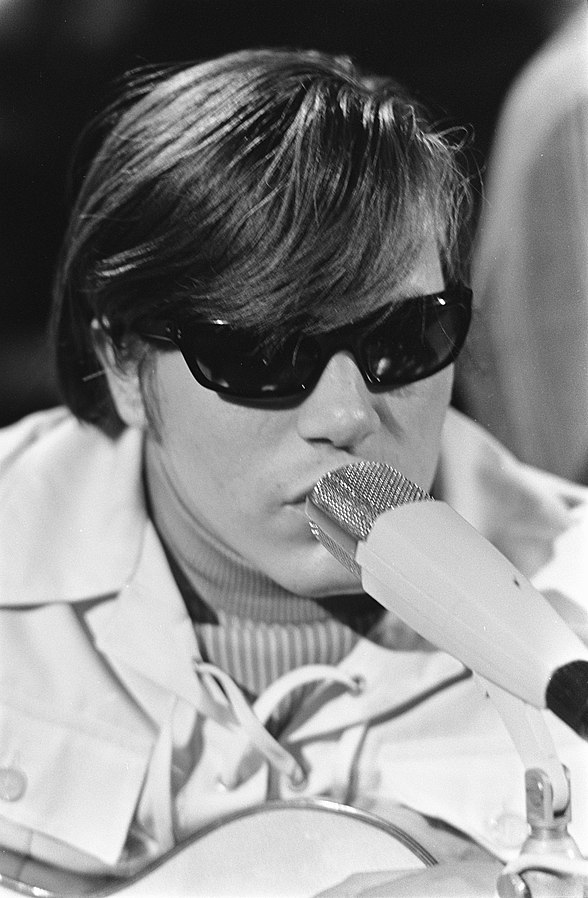

This is all to lead to what I wanted to most strongly share in this post, and is probably the reason for its existence at all: José Feliciano’s 1968 version of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Performed at Game 5 of the 1968 World Series, his performance is commonly credited as the first reinterpretation of the anthem’s music. Following his performance, he was booed and widely derided. And though Feliciano’s rendition has become more broadly appreciated since that first performance, he still stands alone among those who perform the anthem with belting, soaring bombast. I find it difficult to express why Feliciano’s version resonates so much with me, though I suspect it is in the humility of his performance, sounding closer to a protest song than hymn. It feels far more fitting as the song of a nation whose survival was not given; a nation haunted by its worst demons, but which continues to strive to heal and better itself; a nation that has had massacres and liberations.

A nation’s national anthem, as I considered in my recent research, is in many ways one of its most, if not most, important symbols. It declares directly where visual symbols only suggest artistically. In that sense, I’m glad for “The Star-Spangled Banner:” its tale of uncertainty and endurance is mirrored by the nation itself, and the question it asks is one we must never cease to ask and examine.