One fall morning in 2015, as I sat in my Training and Methods course in the Oxford History Faculty, my peers and I were pressed for the answer to a question rather unorthodox for a room full of academics: what was the greatest empire in history? Asked by the late, redoubtable Dr. Jan-Georg Deutsch, the question compelled us all to silence as we contemplated what was so obviously a trap, yet equally a tantalizing opportunity for debate. Boldly (perhaps one might say brashly), I ventured an answer that attempted to dissect the question, which Dr. Deutsch would cheekily have none of. While the discussion picked up from there as first I, then others, offered concrete answers, my original (attempt to) answer has remained my guide in approaching this historical pissing contest. While on the surface this question seems to have little concrete relevance to the serious study of history (it being more the trivial fare preferred by armchair generals or History Channel specials), an assessment of history’s greatest empire can serve to illumine its necessary criteria. In doing so, we can explore the fundamental mechanics of how and why empires are built and maintained, as well as analyzing their legacies. Less a question and more of an exercise, then, my approach amends Dr. Deutsch’s original query. Rather than “What was the greatest empire in history?” I ask “How can we measure historical empires’ greatness?”

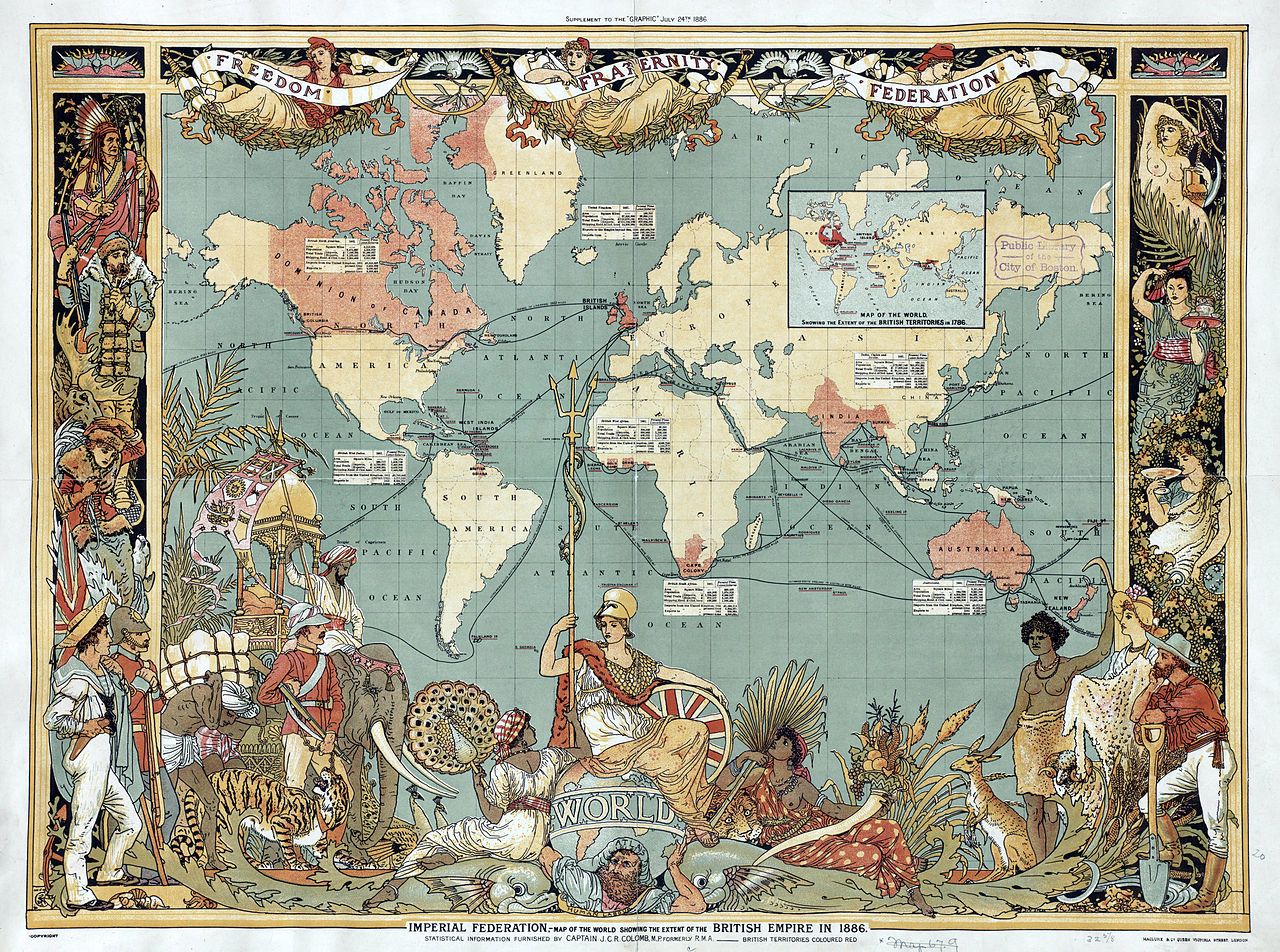

Size The first and most obvious criterion is surface area. If imperialism is to seek extension of a state’s power through diplomatic or military means,and an empire is at its most fundamental the realization of that goal, then the states that were able to extend their power the farthest naturally come to mind for the championship title. By far the leader is Britain’s empire, covering nearly a quarter of the world at 13.7 million square miles. Runner up is the largest contiguous empire in history, that of the Mongols, at 9.1 million square miles. Rounding out the top five are the Russian Empire (8.8 million), Qing China (5.7 million), and the Spanish Empire (5.3 million). The top ten would further include the French Empire, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, Yuan China, and the Portuguese Empire. Noticeably absent is the West’s progenitor, Rome. At only 1.9 million square miles, Rome places twenty-fourth. Even including the surface area of the Roman-controlled Mediterranean and Black Seas only brings it to thirteenth. All the given areas are measured at each empire’s territorial height, which raises the most obvious objection to this criteria: the size of empires fluctuate wildly over time. Size cannot thus stand alone; it must be tempered by other considerations, most notably…

Time I’ve already begun to apply the variable of time in noting that empires do not remain the same size for long. The farthest extent of an empire can last for a few years or for a few centuries. It is tempting to simply modify an empire’s peak extent with that peak’s duration, but even this is impossible. Some empires expand and dissolve quickly; others retract methodically and maintain their new size for even longer. Considering the total duration of an empire is an equally problematic alternative. When is one to start? At the first expansion from city to neighboring city? Or once some arbitrary critical mass has been reached? When, then, to end? At the very end and dissolution of the state? Once decline becomes permanent and unreversed? Does an interruption in rule simply get subtracted from the total, or does it reset the clock? What counts as an interruption, and what counts as the formation of a new state? Chronological quagmires necessarily ensue, and result in this parameter’s ability to be manipulated to deliver any empire you want at the top.

Stability An alluring alternative to temper the consideration of size is the factor of stability. A nebulous term, stability could be simply a measure of how slowly an empire lost territory or, more intricately, the quantification of peaceful or unchallenged rule within the borders of the empire. These options can of course bleed into each other, but the most basic problem to this approach is that it cannot be reliably measured from what sources we have for most empires. Furthermore, empires are inherently unstable due to their accompanying hierarchies of power, so even if comprehensive sources did exist this would be a measure of “least bad” rather than “most good.” Even famous “Golden Age” empires like Rome, the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, and the Han and Tang Dynasties begin to lose their luster upon close examination of the rampant unrest attested to in what sources we do have. Indeed, this could even prove to neutralize size, as the larger an empire the more unstable it can (and most likely will) become.

Profit Size and all its variants have proven a frustrating tangle; what of a pivot to something even more fundamental? States expand to claim a greater share of available resources, so what if we consider the amount an empire profited its core society? Just like everything previously, however, problems start to immediately present themselves. Pre-modern, mostly agrarian societies would be highly difficult to quantify if records even existed. Modern empires might theoretically be possible to tally, yet would require an analysis not only of government finances but the finances of every private business, corporation, joint stock company, shipping concern, and on, and on. This assumes empire is even profitable in the first place; detractors, rulers, and historians alike have noted that, at least in the case of modern European empires, the balance sheet may well have been deep in the red rather than in the black.

Legacy The range of options for measuring the comparative success of empires are thus evidently unfruitful, yet my original question did not ask for the most successful empire but the greatest. Any initial impulse to measure this greatness through an empire’s benevolence should be immediately discarded; along with inherent imperial instability comes inherent imperial brutality, and even the most supposedly benign of empires are only so in relation to others that verge upon unspeakable. But perhaps an alternative is to examine the extent to which an empire has cast its influence down through history. Such legacies are shadows of real power, true, but they can at times demonstrate once-tangible imperial extent. Among these, five loom especially large. Rome, of course, forms much of the bedrock of western civilization and is responsible for the fostering and spread of Christianity. The Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates bear much the same relationship with Islam as well as modern mathematics, sciences, and the shepherding of Rome’s own legacy. Han China proved so influential that it cemented not only the enduring concept of China as one indivisible, continuous ‘Middle Kingdom’ but has forever after given identity to the core Chinese expression of ethnic identity. Finally, Britain and its decolonization is responsible not only for the global prevalence of English and democratic governments, but also the modern political map and its myriad zones of strife. Unfortunately, as with any criterion that departs from numbers, this talk of legacy is not like to deliver a clear winner, yet is the most fruitful if we are concerned with history’s relevance to the present.

By now you can surely see why Dr. Deutsch cut my answer (or more properly, non-answer) short before it could gather such prodigious steam. Though much abbreviated here, it is the process of puzzling out our original query that hears the most fruit, as no single objective answer can possibly be provided. Indeed, someone’s pick for history’s greatest empire gives more insight into their own biases than anything else. All those empires I’ve mentioned above, and likely any others that have occurred to you while reading, are in any case ultimately failures. ‘Unfinished’ may be their kindest description, as none could surmount their inherent instability to create an enduring geopolitical edifice. Perhaps if any state could ever become a ‘finished’ empire as such that would provide a more fruitful answer, but that is a topic for another post.

3 replies on “Size, or How You Rule It? Determining History’s Greatest Empire”

At the risk of being “that guy” (though you may have noticed I like to poke at things), where would you say the USA ranks according to your criteria? Given that it’s not been around very long, comparatively, and certainly legacy is difficult to measure as it is an ongoing experiment, but I am interested. Additionally, how would you quantify empires like the Aztec or the Inca, where relatively little information about them survives?

Astute questions, Riley! Without saying anything more, I would recommend you stay tuned to future posts for my take on your first question. As for indigenous American empires, we do have a surprisingly good amount of information on the empires that existed at the time of European contact, but of course much of their early history melds into myth (as do many ancient Old World empires). Other, older, possible empires like Cahokia or the Anasazi are indeed lost to the ages. As for how they fit my proposed criteria, the Aztec and Inca are both relatively minor, comprising less than a million square miles and lasting for little more than a single century.

Well in that case I await further posts with baited breath!