For fans of science fiction and fantasy, few narrative concepts are held in as great reverence as worldbuilding. Through The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien inaugurated not just a genre, but a writing process that treats the rules, culture, and history of an entire world as critical to the work (as Bryan discussed a few years back). Even elements without direct impact on the main plot are developed and sometimes revealed through the narrative, deepening the sense of immersion. Successful worldbuilding leaves the audience with a sense that there are more stories taking place in the world just out of sight: that the world is more than a two-dimensional backdrop. Nor is such a world static—by the end of The Lord of the Rings, the time of the elves has reached its end and magic itself is fading. These world, simply put, have a history to them.

For fans of science fiction and fantasy, few narrative concepts are held in as great reverence as worldbuilding. Through The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien inaugurated not just a genre, but a writing process that treats the rules, culture, and history of an entire world as critical to the work (as Bryan discussed a few years back). Even elements without direct impact on the main plot are developed and sometimes revealed through the narrative, deepening the sense of immersion. Successful worldbuilding leaves the audience with a sense that there are more stories taking place in the world just out of sight: that the world is more than a two-dimensional backdrop. Nor is such a world static—by the end of The Lord of the Rings, the time of the elves has reached its end and magic itself is fading. These world, simply put, have a history to them.

Not all fictional worlds take this so seriously and often they suffer for it. As much as I enjoy the Old Republic era of the Star Wars universe, set approximately 4000 years before the films, the time difference serves only to distinguish it from established cannon without considering how the universe may have changed over time. Four thousand years is an exceptionally long time—in our world, that corresponds to roughly the time period that Stonehenge was completed, the first Minoan palaces was built, and the final woolly mammoth died. Yet a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, not that much seems to have changed in that time. Conflict between Jedi and Sith Empire? Check. Giant spaceship battles? Check. Lightsabers and laser guns? Check. Ironically, this can be contrasted against the couple decades between Episode III and Episode IV, wherein the Jedi have been implausibly reduced to mythic status despite existing for four millennia beforehand.

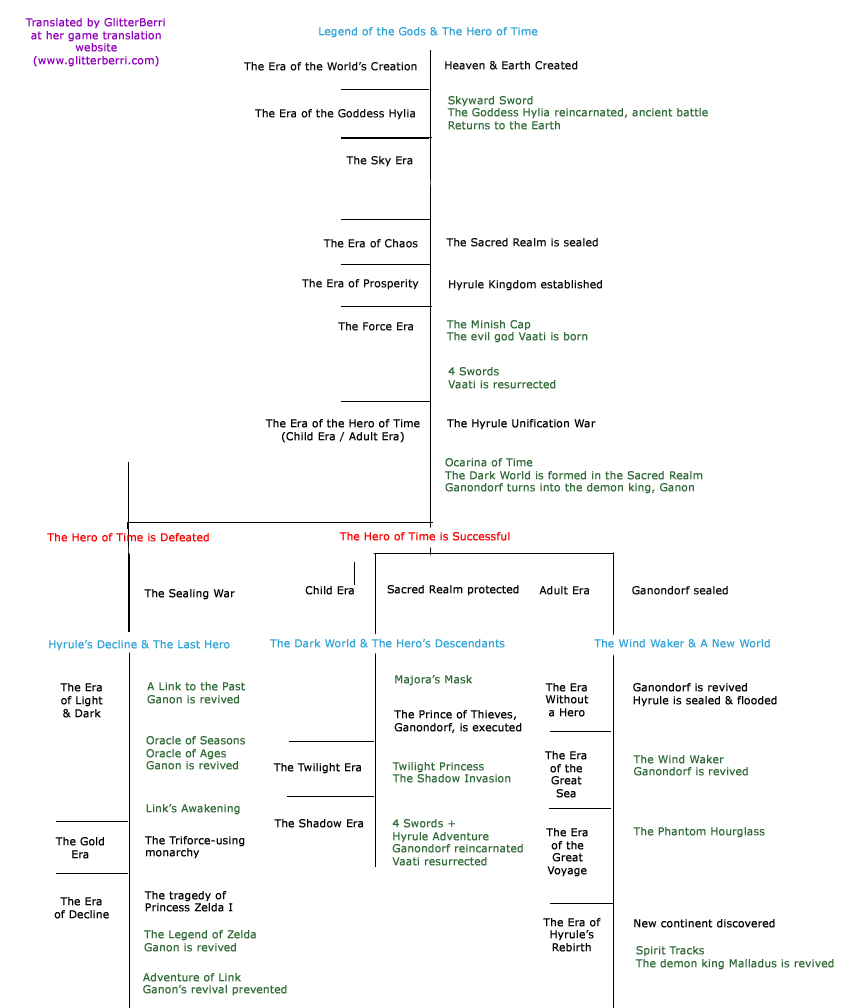

The Legend of Zelda series treats its history even worse, with a splintered timeline that Nintendo has acknowledged as inconclusive and subject to change. The latest game, Breath of the Wild, takes place 100 years after a great calamity that involved advanced weaponry built 10,000 years earlier but still after the existing timeline—and possibly a convergence of all three of them. How many tens of thousands of years does that put it after Skyward Sword? At least Star Wars is clear and consistent about its timeline.

Granted, both the Zelda and Star Wars franchises are premised on cyclical storytelling. Just as each Zelda game follows the monomythic arc with parallels to past games, the Star Wars trilogies are meant to echo each other (think the Death Star and Starkiller Base). But more generally, the way these series handle history comes across as cameos and fan service.

A better example is Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn trilogy and its sequel the Wax and Wayne tetralogy. In the two series, 300 years have passed between the feudal-industrial era of the first books and the industrial Gilded Age setting of the second. During that time, the world has developed guns, trains, and criminal justice. Similarly, the 100 years between Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra represented an age of political and economic prosperity in which industry flourished. Both incorporate industrialization into well-established magic systems, giving a new flavor to the story. Interestingly, both universes also have the implicit message that tyranny and conflict are antithetical to progress, which overlooks the technological developments these have inspired in our own history.

Admittedly, worldbuilding is easier in some mediums than others. Film, television, and video games are restricted by time and budgets in a way that novels are not. Look at the lore of A Song of Ice and Fire compared to its equivalent in Game of Thrones. But neither is this always the case—look at how Dragon Age pulled apart its own mythology in Inquisition, revealing forbidden truths about the true history of the world.

All of this is to say that when a story requires careful worldbuilding, attention to history and historical processes should be part of this effort.