Last Sunday marked the hundred year anniversary of the First World War Armistice between the Allied Powers and Germany, last of the Central Powers to ask for a cessation of hostilities. Surely by now you’ve all seen countless articles and media commemorating the end of the Great War, and 2018 will almost assuredly mark the end of any official centennial observances.

They’re all wrong.

The Great War did not end in 1918. There is actually a burgeoning school of First World War historians, many working in more global aspects of the conflict, who have argued for a general broadening of the conflict to the years 1911-1923, but that is not what I mean. No, take a pen to every history book you’ve ever read. They’ve all overlooked a simple fact: an armistice does not end a war. The armistice that took effect on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918 only paused hostilities; it did not officially conclude them. That conclusion would come with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles (really a collection of international agreements) in June of 1919. Indeed, for the six months of negotiation in Paris, Allied soldiers remained on war footing and were prepared to launch an invasion of Germany in the case negotiations broke down.

Outside Western Europe, the rest of the world only took selective notice of this ‘end’ to four years of war. With a treaty as-yet unsigned, some nations saw a chance to launch campaigns and improve their standing at the peace conference; others tied up loose ends of their own, while the bleeding sore of the Russian civil war was an ongoing concern. In the spirit of unfinished and unremembered conflict, I wanted to commemorate this centennial not with a reflection on the new world order that European diplomats were attempting to forge but by shining a brief spotlight on three wars and military actions that continued despite their best efforts past the conventionally remembered ‘end’ of the First World War.

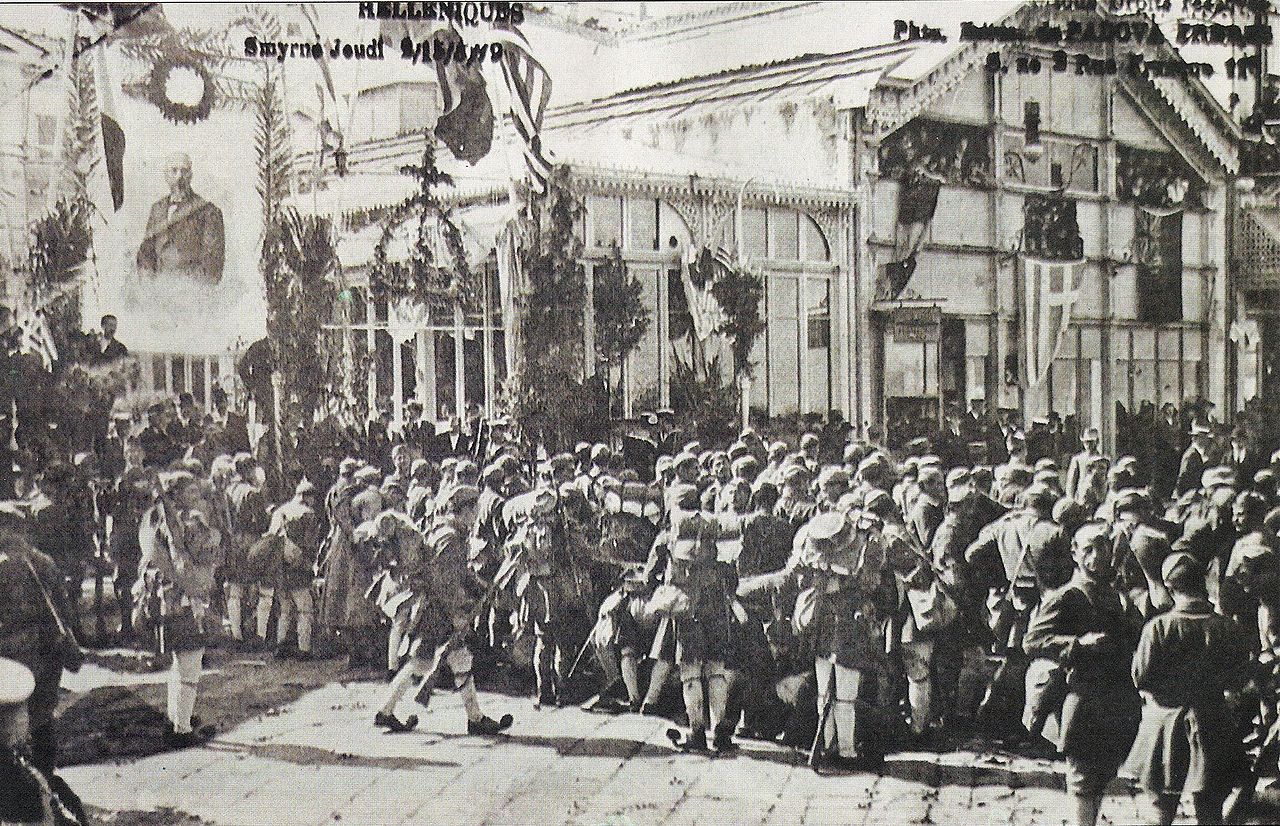

Greece Invades Turkey: Disappointed by the Allies’ failure to deliver on promises that Greece would gain territory at the expense of the defeated Ottoman Empire and motivated by claims of cultural hegemony over the western coast and islands of Anatolia, Greece launched an invasion of its own into Asia Minor in May of 1919. While initially successful, the Greek campaign provided the impetus for the unification of a new Turkish nation-state under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, known to posterity as Ataturk. When the Allies would (or could) not restrain Greece, Ataturk counterattacked and broke the Greek advance, driving them back to the sea and recapturing all lost territory by 1922. Greece was forced to relinquish its claims, and the modern boundaries of both countries were set.

House of Saud Triumphant: In the same month that Greece invaded Asia Minor, fighting broke out between the two Arab factions Britain had supported in their revolt against Ottoman authority in the Near East, the Hashemites and the House of Saud. Seeing an opportunity to seize supremacy in the region, the House of Saud provoked a diplomatic crisis which escalated into full-blown armed conflict and annihilated the Hashemite army. Only British intervention saved the Hashemites from complete destruction, and by July of 1919 Ibn Saud reigned supreme on the Arabian Peninsula. The exiled Hashemites would be given the throne of Iraq in the peace settlement, while Saudi Arabia still bears the name of Saud.

AEF Siberia: As part of a larger Allied intervention to sway the course of the Russian Civil War and safeguard strategic assets, a portion of the American Expeditionary Force was sent in 1918 to Siberia. There they would attempt to keep the Trans-Siberian Railway free of marauders, frozen in place by a commanding officer that believed their purpose was to protect American assets, not directly engage in any conflict with Russia’s warring factions. Conditions were, unsurprisingly, miserable, and the nearly-8,000 American soldiers were ultimately withdrawn in April of 1920, having suffered 189 casualties.