by Francis and Bryan

Beware: This piece is filled with extremely nerdy terminology. We have done our best to explain each piece of jargon as it appears. You have been warned

“Well, we’re back!”

Another Hobbit Day (September 22nd, the birthday of both Bilbo and Frodo Baggins in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth) has passed. This year, rather than singing dirges of fallen Gondolin now that we must wait another 365 days to eat a third breakfast (also known as elevenses) without shame, we decided to look at some of the lesser known historical inspirations for crucial civilizations in Tolkien’s Middle-Earth. That Tolkien used historical inspiration should come as no surprise to even the most casual fan; Tolkien set the stage for fantasy settings to this day with his use of medieval imagery and iconography. Aside from general flavor, however, and avoiding the problematic cultural mix that resulted in some of Tolkien’s antagonistic peoples, there are in fact specific historical entities that gave rise to elements of Middle Earth. Specifically, our focus will be on the kingdoms of Gondor and Rohan, the stalwart realms who paid the price in blood and tears to defend the Free Peoples of Middle-Earth from Isengard and Barad-dur at the climactic battles of Helm’s Deep and Pelennor Fields.

Dreams of Past Glory: Gondor and the Heirs of Numenor

Gondor is the most ancient kingdom of men in Middle-Earth. Founded by the Numenoreans, a race of men gifted by the Valar (gods) with long lifespans (think 250-300 years on average), Gondor began when Numenoreans loyal to Eru (GOD) escaped their doomed homeland of Numenor (which was Middle-Earth’s Atlantis) and founded two kingdoms, Arnor and Gondor. These two kingdoms were peopled by the Dunedain (men with Numenorean ancestors) and united by oath and kinship. By the time of The Lord of the Rings, the king’s family in Arnor lived through Aragorn, though Arnor had been destroyed by invasion and conquest, while Gondor’s kings had died, but the kingdom remained in the hands of the stewards: Denethor and his sons Boromir and Faramir.

Gondor stands as the last line of defense for much of Middle-Earth against the legions of Sauron. Without the One Ring, Sauron is forced to wage a war of conquest to dominate Middle-Earth and seeks to conquer his enemies as they set out to destroy the source of his power, the One Ring. As a kingdom much reduced by invasion, plague, civil war, and conquest, Gondor’s first historical antecedent is the much-forgotten Byzantine Empire, the Eastern half of the Roman Empire that survived (and thrived for a time) after the fall of the Western Roman Empire to invading barbarian tribes and internal political collapse.

Moreover, the similarities between Gondor and the Byzantine Empire extend beyond the large historical timelines of these kingdoms. Not only is it true that the eastern half of Dunedain and Roman civilization survived (Gondor and the Byzantine Empire), but these empires were also centered on a powerful city that controlled trade, governance, and culture in the empire. For the Byzantine Empire, this was the walled and heavily fortified city of Constantinople that guarded the entry into Europe. For 800 years, Constantinople waged nearly constant wars against Islamic conquerors who sought to take the city and expand Islam and their territorial control further into Europe. Against the might of these Islamic kingdoms stood Constantinople, defending a Christianized West from the Islamic East (with some counter-conquest in reply as well, i.e. the First Crusade). In Gondor, this city was Minas Tirith, built as a seat of kings (like Constantinople) and fortified to defend Gondor. The armies of Minas Tirith held back the tide of Mordor’s legions and even engaged in campaigns of counter-conquest to subdue Mordor’s allies. Tolkien even writes his own “how it should have ended” for his own Constantinople, with Minas Tirith surviving Sauron’s assault in the finale of the trilogy.

The theme of “rebirth” is found not only in Minas Tirith, and Gondor’s, location as the seat of Aragorn’s new kingdom. It is also present in Gondor, and Minas Tirith’s history, as the center of human culture, achievement, learning, and lore in Middle-Earth. It is to Minas Tirith that Gandalf goes to research the history of the Rings of Power and it is the “silver trumpets” of the city that recall the glory of Numenor and the splendor of Gondor’s history, a civilization in decline until Aragorn’s return, but not one without its majesty. Its status as the “first among equals” of all cities of men in Middle-Earth speaks to another historical inspiration of the Kingdom of Gondor, the Renaissance city-state of Florence.

During the High Middle Ages and Renaissance (1200s-1500s), Florence was the center of cultural, artistic, and humanistic endeavors in Europe. It was in Florence that the Renaissance began and where scholars, statesmen, saints, popes, clergy, soldiers, and artisans all intermixed as European culture immersed itself again in the legacies of Greco-Roman culture. Minas Tirith represents such a place in Middle-Earth, one that is accessible to all the Free-peoples, and not shrouded in mystery like Rivendell or Lothlorien, the ancient dwellings of the elves.

The cultural similarities between Minas Tirith and Florence are further supported by similarities in geography between Middle Earth and Europe. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth begins in the Shire, an idyllic land of pastoral Hobbits who live for food, friends, good tilled earth, and tobacco. The Shire is modeled, in many ways, after Oxford and its surrounding region in England, the place where Tolkien grew up, lived, and worked as a professor. If one takes Oxford to be the Shire, and overlays a map of Europe over that of Middle Earth, Florence happens to be approximately where Minas Tirith is in relation to the Shire. Consequently, the geographic parallelisms of our world and Tolkien’s Middle-Earth conveniently reveal a correlation between Oxford and the Shire and Minas Tirith and Florence.

Flaxen-haired Invaders: The Rohirrim and Dunlendings

The Kingdom of Rohan makes up the other half of the “Men of the West” during the events of The Lord of the Rings. Rohan is the land of the horse-lords, a proud, warlike people renowned for their horsemanship. Originally a nomadic people known as the Eotheod, the Rohirrim settled the lands north and east of Gondor after the latter kingdom gave them gratefully as a reward for aid in a dark hour against Gondor’s Easterling foes. In The Lord of the Rings, the Rohirrim prove vital in checking the power of the traitorous wizard Saruman and breaking Sauron’s siege of Minas Tirith.

The historical inspirations for Rohan are less political and more cultural, and those familiar with Tolkien’s personal history are likely already aware of the source. At Oxford, Tolkien was a professor of Anglo-Saxon (also known as Old English), the language of those Germanic peoples that settled Britain following the collapse of the island’s Roman infrastructure in the fifth and sixth centuries AD. Indeed, Tolkien’s lecture on Beowulf (The Monsters and the Critics) has profoundly impacted literary criticism of that epic poem to this day.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Tolkien’s beloved Anglo-Saxons found their way into Middle Earth. From personal names like Ceorl, Eomer, Theoden, Eowyn, Elfhelm, Freca, and Gamling to place names like Edoras, Aldburg, Dimholt, and Meduseld, the language of the Rohirrim is almost identical to Anglo-Saxon, and their physical description as tall and almost universally blond fits the general memory of Britain’s Germanic settlers. The Rohirrim congregate in mead halls to listen to bards regale them with songs of past heroes and monsters, and their metalwork bears the kinds of scrollwork and motifs so reminiscent of Dark Age Britain. Anglo-Saxon society did not revolve around horses, but even this bears an explanation: one story (possibly apocryphal) states that Tolkien believed the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms could have survived the Viking onslaught if only they had possessed effective cavalry.

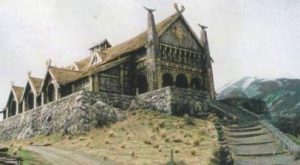

For all this cultural flavor, there is one bit of ‘political’ history that only confirms the Rohirrim in their role as quasi-Anglo Saxons. When granted the old Gondorian province of Calenardon, the Eotheod did not settle an empty land. The original inhabitants were expelled, chased to the rocky lands to the west. These peoples, eventually known as the wild men of Dunland, or Dunlendings, harbored intense hatred for the invaders that had taken their land, and intermittent conflict existed between the two for centuries. This calls to mind the traditional accounts of the Anglo-Saxon arrival in Britain, expelling the native inhabitants until only Wales and Cornwall remained as bastions of Romano-British culture. Even the fortress of Helm’s Deep (originally built as a refuge from the Dunlendings) contains a reference to this heritage; unseen in the movies, the fortress is fronted by an earthwork known as Helm’s Dyke; in Anglo-Saxon Mercia, Offa’s Dyke separated the lands of England from the ‘savages’ of Wales. Other media have seized on these similarities and taken them even further; the popular video game The Lord of the Rings Online, for example, attributes native British-inspired spirituality and even architecture to its Dunlendings.

These two proud kingdoms of Tolkien’s mythology only scratch the surface of what can be said historically concerning Middle Earth, and rest assured, we are far from done exploring! For now, however, we must bid mae govannen; come next year and another Hobbit Day, we look forward to treading these paths with you again.

One reply on “The Historical Middle Earth: Men of the West”

Great piece. I’m wondering whether you think all of these are intentional or whether this is more a discussion of historical antecedents. Tolkien obviously brought a lot of history into his work, but I’m amazed by things like the geographic relation of Gondor and Florence.