Has there ever been a subject that captured America’s imagination like the Wild West? What American triumph more glorious than the Winning of the West? What more iconic (and retroactively troubling) childhood memory than playing cowboys and Indians? What films more seminal to the American film tradition than those staring John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Roy Rogers?

We know, of course, those movies are basically all wrong. As films, they may be enjoyable to watch if you can get past the whitewashing and archaic gender roles, but they belong to the realm of memory, not history. Western films conjured up the West that Americans wanted to imagine, not the one that actually existed.

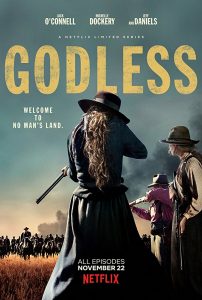

The Western genre lives on as a cultural touchstone, but one so worn and tired today that anyone hoping to make it work must push beyond the well-trod wagon paths of the twentieth-century tropes. The video game Red Dead Redemption earned critical acclaim in 2010 and has a sequel queued for later this year. HBO’s Westworld gave us a meta-look at the genre by nesting it in sci-fi. But it’s not just technology and the push for originality that are changing the Western. In defiance of claims of ‘political correctness,’ our own changing culture is pushing the envelope of what kinds of stories can be told through the genre. Netflix’s Godless epitomizes this potential.

There’s no way around this point so I’ll say it first: Godless moves slowly but rewards patience. The episodes average around 70 minutes but range from 40-80 depending on the place of the narrative. Slow and deliberate exposition means that it takes a few episodes to understand the backstories enough to relate to the characters. Even then, the characters remain remarkably guarded for a character-driven show. Moreover, rather than omit the tedious tasks of daily life in the American West, the show depicts them as everyday acts of survival: from carpentry and hunting to cooking and caring for horses. The inclusion of these scenes speaks to how original content from streaming services can overcome the limitations of traditional runtimes and pacing, but it may not be everyone’s cup of tea.

Happily, however, the show is filled with beautiful cinematography and wide-angle shots that help compensate for (and complement) the slow narrative pace. The cast is phenomenal, too. Fans of Downton Abbey and The Newsroom will enjoy seeing some favorite actors in key roles. Sam Waterston and Jeff Daniels each sport magnificent facial hair as they clash in what at first appears to be a classic Western story of good guys and bad guys. For her part, Michelle Dockery takes her best shot at an American accent as a strong and guarded widow living on the edge.

But what is it that makes Godless different from your grandpappy’s Westerns? True to its name, this show is dark. Not a romantic cowboy flick, the show depicts a gritty borderlands plagued by disease, rape, captivity, and brutal violence—heavy themes it handles without glorifying or trivializing them.

More importantly, the Wild West of Godless is no white man’s libertarian fantasy. The show offers positive portrayal of the diversity of race, religion, sexuality, and ethnicity that made up the Wild West. Characters are informed but not determined by their experiences and identity. By the third episode, I was growing concerned about the lack of people of color but it turned out there was good reason: a group of retired USCTs and Buffalo soldiers had formed a self-segregated community that appeared in that very episode. Meanwhile, the white settlers are not cast from the mold of the eternal American—many are shown as immigrants or outcasts going West out of desperation as much as opportunity. Likewise, Native Americans are spared the monolithic caricatures of Western tradition, being treated neither as blood-thirsty barbarians nor as noble savages. The show instead depicts the range of reactions to white settlement, from violence and resistance to cooperation and coexistence.

Just as important, the show corrects the record on women in the west. Its female characters are tough and courageous. La Belle, the main town in the show, is almost entirely female, the consequence of a mine disaster that killed most of the men. But the ladies of La Belle were not just empowered because they had no men to lean on; even before the tragedy, the women are shown to have been an essential part of the Western story. This is most explicit in how the show treats the sex trade as an economic engine of boomtowns, depicting sex workers not as victims or objects deserving of our mockery, but as clever and driven women who were at the heart of Western expansion.

I was surprised not to see any caballeros make an appearance, which would have made more sense if the show was set in Wyoming, but in New Mexico it seemed to be a striking absence. Like any work of historical fiction, Godless is no magic lens into the past. Its corrective efforts, well-delivered, are much appreciated but shouldn’t be mistaken for historic Truth. (Then again, historians’ own efforts can only be considered aspirational in their pursuit of Truth). Moreover, despite its emphasis on representation, the show struggles and ultimately fails to shift the focus of the plot away from the two white men at its heart.

Still, Godless feels like a different kind of Western. It’s hard to imagine such a show predating the Netflix era, not only because of the freedom allowed by the streaming format, but because of the cultural turn we’ve taken since the mid-20th century that has allowed us to revisit these iconic stories and to tell them differently. Some people might dismiss such efforts as ‘political correctness’ intruding on a sacred American tale; a historian would call it historical correctness pushing back against a myth. As Godless proves, however, you don’t have to sacrifice narrative to tell an inclusive and representative story. Instead, the complexities of the past can breathe new life into the most iconic American genre of all.

Further reading:

Gilbert, Sophie. “What ‘Godless’ Says About America.” Atlantic, November 27, 2017.

One reply on “Not God’s Country: Netflix’s Godless and the New American Western”

A friend of mine has been pushing me to watch this, thanks for the reminder!