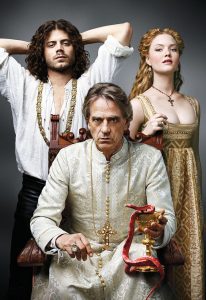

As any history lover is wont to do, I recently combed through Netflix and added every period piece that I could find to my watch list. I decided to begin, well, at the beginning, or at least with the earliest on my new list. Thus I came to Showtime’s 2011 series The Borgias, starring Jeremy Irons as Rodrigo Borgia, the Renaissance Pope Alexander VI and patriarch of a famously corrupt Spanish noble family. The show itself was highly entertaining, full of intrigue, backbiting, and monologues that have become the hallmarks of prestige television. As always, Jeremy Irons is magnetic, and even though the Renaissance has never been my specialty, his performance sustained me through events that otherwise might not have kept my interest. As I prepared to review The Borgias, however, I realized that I lacked any foundation for such an historical review. I thus dutifully hunted down a history of the family, and so we come to this tandem review.

Unlike many similar possible studies, reading Hibbert’s work meshed almost too perfectly with its accompanying media. Indeed, at times I even wondered if The Borgias and their Enemies had been written as a companion piece for the show or, once I compared dates, perhaps served as inspiration. The history of the Borgia family is nothing if not lurid; capturing the papacy at the height of the Renaissance, Alexander VI and his children moved amongst the cultural treasures of the time while playing key parts in its accompanying corruption and decadence. After establishing a brief history of the papacy and Rome since 1300 for context, Hibbert’s narrative (and it is indeed a narrative; do not come seeking any kind of analytic argument here) follows the story of the Borgias in minute, scandalous detail. Every plot, every rumor, is given its due in magnificent fashion with a focus that exhaustively documents the family’s history and unfortunately little else. Perhaps the inherent pulpy nature of the Borgias is the reason why I could not find any general history of them written more recently than a decade ago, and why Hibbert’s work was purportedly the first major biography of the Borgias in thirty years. This is a shame; there exists so much potential to explore the wider European history of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries through the lens of this family: the discovery of the Americas from a southern European perspective, the eroding prestige and authority of the Church, the ascent of France, the fragmentation of Italy.

Now, back to my original intention: The Borgias! Armed with my newfound knowledge courtesy of Hibbert, I could see that this show is perhaps a bit more creative with its history than other period pieces that purport to portray real events. A canny viewer might see echoes of different events folded into others for narrative convenience, but others seem to have been invented from whole cloth, and some of the character traits of the main characters have been swapped (for example, it was Cesare, not Juan, Borgia that suffered severely from syphilis. Though, from Hibbert, you get the impression that pretty much everyone who was anyone in sixteenth-century Italy had syphilis). Intriguingly, though the Borgias are the protagonists of this series, the show chooses to portray the relationship between Rodrigo’s children Cesare and Lucrezia as actually incestuous, giving credence to what in Hibert are portrayed as baseless, vicious rumors spread by enemies of the family.

Between show and movie, then (not to mention playing some Assassin’s Creed games), I feel much more ready to take on the other Renaissance offering on my watch list. If it weren’t for some of its adult content, I would even recommend The Borgias to my AP European History students, as the visual medium of television can show the opulence and mundane corruption of the Renaissance in ways books cannot. Whether you’re looking to expand your horizons like me, or are a Renaissance fanatic looking for your next fix, I’d imagine you’ll have a good time with both of these Borgia-filled offerings.

2 replies on “Bushels of Borgias: Christopher Hibbert’s The Borgias and their Enemies and Showtime’s The Borgias”

There’s another Borgia TV series made by a collaboration of various European TV stations which you should be able to find on DVD. It’s definitely worth a look but in the European style it does turn the adult content up to 11. For an interesting comparison of the two series, see my second link below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borgia_(TV_series)

https://www.exurbe.com/the-borgias-vs-borgia-faith-and-fear/

Thanks for your comment, Tony! In fact, I began my Netflix period piece journey with the other Borgia show, not realizing it wasn’t the Jeremy Irons version at first, and when I looked for the differences between the two shows, the first thing I read was your post comparing them! Loved your piece, and I wish I would have moved faster to finish the other show before it disappeared from Netflix (to be replaced by this one). In fact, I have another post going up next week reflecting on some of the ‘toning down’ that you noted in Showtime’s series.