In the third installment of his series unpacking Supreme Court Cases that reveal unsavory truths about our country and how the legal interpretation of its founding principles have evolved throughout the centuries, Bryan explores how the crime of treason has never been as straightforward as it sounds.

“Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.”

Thus opens and closes the Constitutional definition of treason, contained within Article III, Section 3. The document goes on to state the process for convicting someone of this crime: “No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.” If this all sounds hyper specific, that’s because it was meant to be. Under the Old World monarchies that the Founders were escaping and rejecting with their new model of political process, treason had been habitually abused to persecute enemies of the regime, real or imagined. As with so many things in the Constitution, however, what seems straightforward at first glance is actually open to a whole world of interpretation. How does one define levying war against the United States? How does one define enemies, aid, comfort? Can treason only occur during time of war? As the new nation found its sea legs and began actually governing in its opening decades, these issues would come to a head in one of the earliest and highest profile charges of treason in our history.

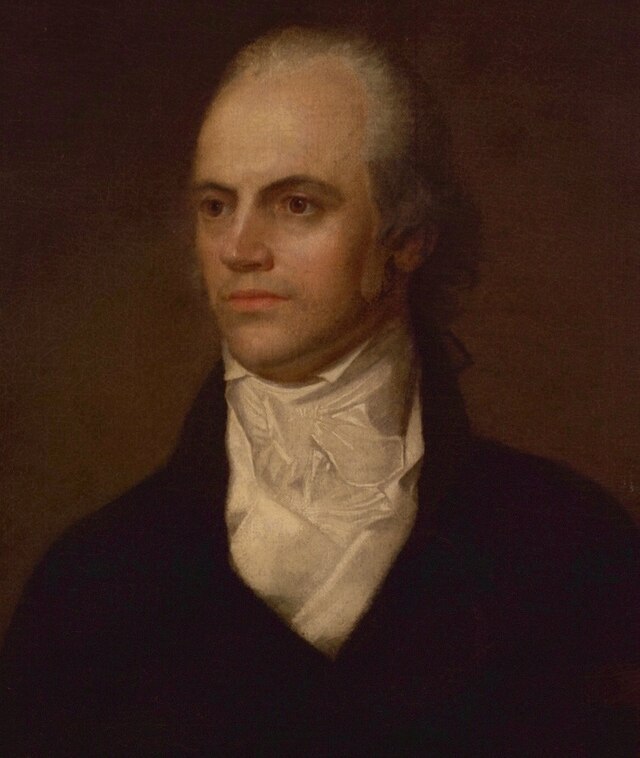

Aaron Burr may be one of the most (in)famous Americans who never became president. Modern audiences are likely most familiar with him from Lin Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton, in which he plays the antagonist and ultimate killer of the titular character. What Hamilton doesn’t relate, however, is how Burr’s life spiraled out of control after his rejection by both the Democratic-Republican and Federalist parties in the wake of his unsuccessful presidential campaign and duel with Hamilton. A political opportunist and proto-populist in many ways, Burr conceived of a plan to head west and make something of himself in the fluid frontier where American interests met British and Spanish possessions. Just what he intended to build, however, is unclear to this day. At the very least, Burr attempted to recruit settlers for a some kind of filibustering expedition or adventure to seize Texas and/or West Florida from Spain. One of his partners in this venture, however, leveled even more serious accusations. Commanding General of the US Army James Wilkinson, himself in the secret pay of Spain, wrote to President Jefferson in 1806 stating that Burr intended to provoke a rebellion to detach the western states and territories, including the crucial port of New Orleans, from the United States and create a separate country under his own rule.

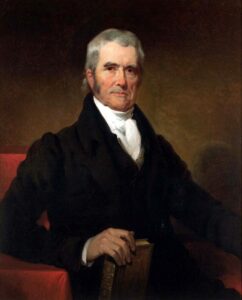

Jefferson needed no more persuading and issued a warrant for Burr’s arrest. Finally captured in 1807, Burr was returned to Washington for trial on the charge of treason, which would be presided over by Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall. As one might expect from such a messy conspiracy, the trial itself would not be straightforward or uncontroversial. Jefferson did himself no favors by declaring to Congress that he had no doubt of Burr’s guilt and that he should be found guilty–without any evidence or jury deliberations of any kind having yet taken place. The administration then did not fully cooperate with Marshall’s subpoenas for evidence, only providing edited sections of relevant correspondence. Unsurprisingly, a case built on hearsay and circumstantial evidence resulted in Burr’s acquittal, but Marshall himself did everything he could to encourage that verdict. While his own Federalist party had used a broader, constructive approach to charging treason in the attempted insurrections of the 1790s, Marshall now dictated an extremely strict construction of the crime. Not only did he insist on the testimony of two witnesses to the same act, but he stressed the use of “overt,” arguing that this meant only an actual insurrection or act of war could be considered treason. Rhetoric, plans, organization, arming, even marching to a rendezvous were all protected under the First Amendment and could not be prosecuted if they did not ultimately result in action against the government.

There is much to like and dislike in Marshall’s foundational jurisprudence of treason. His insistence on hard, corroborated evidence is an admirable one, and unfortunately has not been present in American history as we would wish. His definition of overt acts, however, still has me scratching my head. Speaking out against the government is a very different action than actively planning and organizing its downfall, and I agree with Jefferson that IF the worst allegations against Burr were true and provable and he fully intended to raise a rebellion of Western states, then his own failure to successfully pull off his plot should stand to his credit in his defense. I cannot help but think that if it weren’t for such lenient, restrictive treatment of treason at the founding that perhaps later acts such as the rebellion of the Confederate States or the attempted January 6, 2021 coup might have met with the harsher penalties they deserved. Yet at the same time, knowing our country, there is an equal or greater chance that those penalties would have instead been applied to oppressed peoples in pursuit of their own denied rights and that “race riots” and even nonviolent speeches of the Civil Rights and other movements could have been prosecuted as treason and made a mockery of our other freedoms. There are no easy answers here–a perfect inclusion in this series.