In the months leading up to the election, I told anyone who would listen that they might consider brushing up on the elections of 1876 and 2000. Even before a global pandemic and widespread civil unrest dramatically altered 2020’s course, it seemed clear that this year’s presidential election would be special. The Republican Party’s long, steady anti-democratic march towards authoritarianism made the critical step of fully embracing a cultish leader. The Democratic Party’s anger and frustration over three years of Trump rule foretold high voter enthusiasm, even as the party continued to wage war on itself over which lessons should have been learned from the last election.

And then, of course, 2020 actually began. The worst pandemic in a century upended the economy, threatened voting procedures, and divided voters along largely partisan lines over its very existence. America’s long simmering but often ignored racist past and present came to a head when a Black man’s life was violently extinguished on the streets of South Minneapolis, igniting protests across the nation, some of which turned violent between protesters and law enforcement or counter-protesters. As the election neared, tensions over each of these historic events combined with questions of election integrity real and imagined.

This is perhaps an early draft of how the 2020 election will be contextualized in future history books, but how can and should the election be contextualized against historic past elections? How did 2020 compare to 1876 and 2000, which I thought for sure would serve as apt parallels? To best analyze potential comparisons, I thought it best to break my analysis into three parts: voting, results, and aftermath.

Voting

While it will still be a while until every vote is counted (New York in particular is proving to be especially tardy), it’s already very clear that voter turnout in 2020 was the highest in over a century. The Washington Post projects that when all is said and done, 66.8% of the voting-eligible population will have cast a ballot, the greatest share since 1900 (My current home state of Minnesota once again led the pack with a record 81.6% turnout). While higher than even the high turnout elections of the 1960s, turnout paled in comparison to the mid- to late-1800s, where turnout routinely topped 70% and even 80%.

Of course, no discussion of voter turnout can be complete without discussing voter suppression and voting access. Turnout will almost always be lower when fewer people are allowed to vote. Indeed, if Southern Black voters were included in the voting-eligible population (as they arguably should) for the elections starting in 1868, turnout would be much lower for the elections in the next century. Voting access in 2020 did not have nearly as many racialized impediments as the Jim Crow South, but voting access has been trending downwards over the last decade. Following the gutting of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder in 2012, many states have pursued Voter ID laws, voter roll purges, and targeted polling location closures that have made it increasingly difficult for Black, elderly, young, and transient voters to make their voices heard. The Covid pandemic has complicated this trend, with many states increasing their access to mail-in voting while also potentially driving down voter access due to hampered Get Out the Vote campaigns and shuttered polling places. Given these factors, 2020 seems to stand out without a clear precedent.

In the days preceding this year’s election, businesses in the nation’s capital and other cities across the country shuttered their doors and boarded their windows in anticipation of potential violence. Given the widespread civil unrest that happened over the summer, this did not seem out of the realm of possibility. Nor would it have been without precedent. The Reconstruction elections of 1868, 1872, and 1876 each saw widespread political violence at polling places. These and off year midterm and local elections were defined by violent voter suppression efforts, political assassinations, and the overthrow of democratically-elected local leaders. Fortunately, this scenario did not come to pass. The notion that it was a distinct possibility–one likely enough that business would shutter their doors for days–shows that election day violence may have been the closest to coming to fruition in over a century.

Results

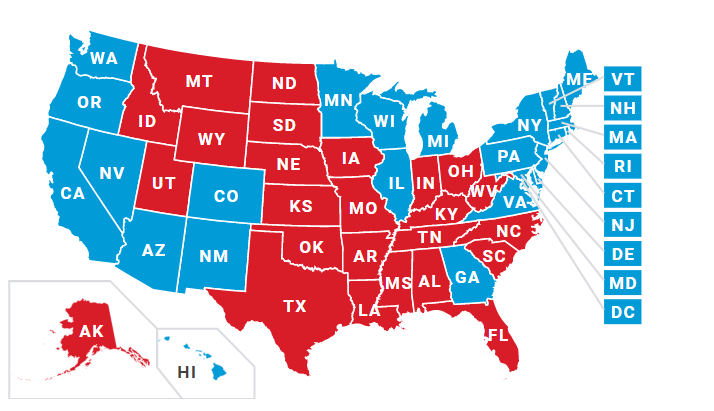

The 2020 election was not particularly close. It was also not a landslide. In this regard, 2020 was a fairly average election. But it felt close. For nearly a week, America and the world waited in suspense to know the results. Some are still waiting, deluded into a false sense of uncertainty.

Waiting a few days for a definitive result is nothing new. Until 1845, there wasn’t even a single election day. Even then, most close elections through the 19th and even the 20th centuries resulted in delayed victories. Often, the country waited days or weeks as votes were tallied and reported. 2020 therefore fits somewhere between the extra day it took for the famously miscalled 1948 election between President Harry Truman and Thomas Dewey and the extra week in 1888 when Grover Cleveland defeated James Blaine.

Of course, it is not unheard of, even in living memory, to wait much, much longer. Indeed, the defeated President and many of his supporters believe that 2020 fits in this category. In 2000, the election was called a month after election day, when the Supreme Court ruled on ending a recount in Florida and after many ballots were discounted due to ballot malfunctions. The President’s campaign and legal team seemed at one point to want to use 2000 as a playbook, seeking to have certain ballots discounted in court before the results could be certified.

In 1876, America waited even longer. After an election that to this day holds the highest record for turnout despite being marred by violence and fraud across several key unreconstructed states in the South, Congress passed a bill creating a bipartisan committee to resolve which slate of electors should be selected in the disputed states. While the committee declared Republican Rutherford B. Hayes the victor a mere days before Inauguration Day, Democratic leaders only agreed to accept the results after Hayes pledged to remove federal troops from the South.

These two extreme examples were the result of severe voting irregularities in one or a few key states. In both of these historic cases, ballots themselves hung in the balance. In 2020, however, ballots were counted prima facie. The election only seemed close and prolonged because of more time needed to count the votes.

Aftermath

Presidential transitions can be tricky. Even when a defeated candidate or incumbent from the defeated party concedes, there may still be bad blood. The transitions between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, James Buchanan and Abraham Lincoln, Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt, and even Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower were less than seamless. To date, the defeated President Trump has refused to even concede and his allies in the federal government and conservative media are determined to hamstring the Biden transition team. This would appear to go beyond precedence and beyond personal or ideological squabbles in the lame duck period between new and old.

Most elections come and go with all the pomp and circumstance of the campaign and election day but little else. A select few do not. 2000 and 1876 stand out for more than their prolonged victory declarations. In both cases, the losing sides grumbled about their loss and cast aspersions–many well-founded–on the circumstances of their defeat. But for the most part, grumblings were just grumblings, nothing more.

The election of 1860 was a different story, one that is well known and needn’t be elaborated upon further. Time will tell whether the aftermath of the 2020 election will look more like that of 1876 and 2000 or 1860. Fortunately, partisanship is less geographically sectional than in 1860 and long term pre-election political violence less widespread (though notably not entirely absent). Unfortunately, there does not yet seem to be a clear path forward for a concession or admission of defeat on the part of the incumbent president’s most devoted (and not coincidentally most well-armed) supporters.

When all is said and done, I think 2020 will stand on its own, without clear precedent or apt comparisons. What is very clear, from even this early draft of history, is that 2020 will already be seen as historic for its conditions and consequences. What remains to be seen is whether its aftermath will further add to its legacy.