In the waning days of December 2021, Bryan and Heather took advantage of their new Alabama home’s proximity to lesser-visited historical sites and embarked on a drive southwest to Andersonville, the infamous Confederate prison where tens of thousands of captured Union soldiers were subjected to hellish confinement between 1864 and 1865. Having worked at the site as an intern during college, Heather was interested in what Bryan might think of the disparate experiences of historical interpretation there. This is the second post in a series documenting those thoughts. The first can be found here on Concerning History.

I expected to experience many things at Andersonville National Historic Site. Mind-numbing atrocity. Somber interpretation and reflection. Respectful memorialization. All these were, for their part, present. But one thing I had not expected to hit me so hard was Andersonville’s beauty.

Those who’ve visited Civil War battlefields, especially Gettysburg, might know something of the beauty of which I speak. The preservation of these sites, many in a conscious effort to freeze time in the pastoral landscape of the mid-nineteenth century, leads to them becoming as much nature preserves as monuments to fratricidal conflict. For me, the fall and winter months especially bring with them a certain stark beauty to these sites as one looks out over swathes of hibernating grass and leafless trees shivering in the chill wind. As we left the Andersonville Visitors Center that balmy December afternoon, I was struck by that same phenomenon there, the locus of so much human suffering. From certain spots as we drove, we could look out over the prison camp’s entire original 16 acres of rolling Georgia fields, split by a picturesque stream flowing between two hills. It was almost idyllic. And it couldn’t have been more different than the history we were there to learn about.

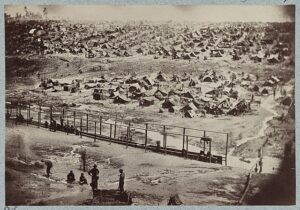

Nearly one hundred and fifty eight years before our visit (and exactly so at the time of this post’s publishing), in late February of 1864, the prison known as Camp Sumter began housing its first Union prisoners. Constructed to draw prisoners of war away from embattled Richmond and into an area with a better supply of food, the camp now known as Andersonville covered just over 16 acres and was designed to house ten thousand men. As Confederate mistreatment of captured black soldiers and the calculus of war led Ulysses S. Grant to shut down prisoner exchange, however, Andersonville soon grew far beyond its capacity. Even though it would expand to twenty-six acres in June of 1864, it would hold thirty thousand men only two months later, its only source of water fatally fouled by all manner of human waste (for perspective, the 1864 population of Atlanta was only twenty thousand). Thirteen thousand men would eventually die there from malnutrition, injury, and disease before the camp closed only fourteen months later.

As I looked out across that field, I saw Andersonville National Historic Site, but I could not truly say I saw Andersonville. It struck me that, while so many American Civil War sites claim to restore their grounds to how they would have looked at the time of the battle, what they really mean is that they have been restored to their appearance just before forces clashed across their fields. For all its carefully placed batteries of cannon, Gettysburg will never truly reflect its face of conflict until the fields are churned up by shot, shell, and thousands of marching shoes, Willoughby Run flows red, and a charnel reek settles over its hills. In that moment at Andersonville, I almost could not stand the bucolic peace in front of me. I wanted the entire stockade to have been reconstructed; I wanted the entire field torn up and reduced to mud, dotted with makeshift shelters; I wanted to have to retreat to our car to escape the stench of thirty thousand men crammed into twenty-six acres with no clean water and no sanitation.

I know, upon reflection, that such an approach to interpretation would likely cost far more money than the NPS receives, and that it also runs the risk of feeling like more of a Civil War theme park than an historical memorial (though some might argue other sites like Gettysburg have already crossed that line). Yet years ago, when writing for Gettysburg College’s Civil War Institute, I argued that leaving the cause of the Civil War out of battlefield interpretation because it “wasn’t military” meant that the casualties displayed so prominently were robbed of their meaning. I feel much the same about representing the horrors and atrocities of this war in visceral fashion to the many visitors who traipse across its fields. Pictures are certainly worth thousands of words, but nothing can match the actual experience, and, for now, that experience is a little too idyllic for my tastes.