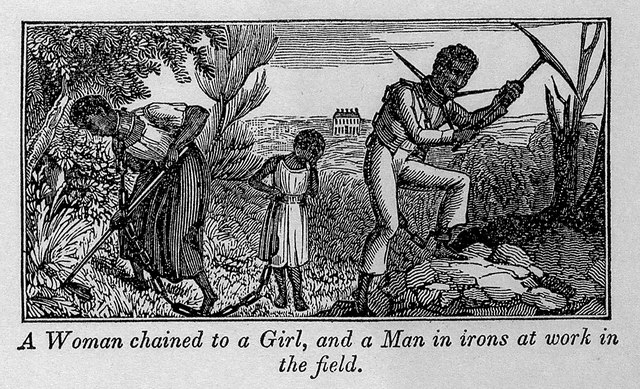

As I recently sat reading on the porch of our new apartment, appreciating the approaching thunderheads like only a child of the East Coast too long on the West Coast can, I encountered a curious assertion. In discussing antebellum slavery in the Deep South and Alabama in particular, the author admirably debunked the Southern myth that slaves were happily cared for by their masters before then boldly stating that the abolitionist narrative of slavery’s pervasive brutality was equally one-sided. The ensuing arguments were well-reasoned. As there was never any systematic study of slavery’s conditions and masters’ behavior conducted, all our evidence is necessarily anecdotal. Those accounts form such a body of evidence that it is clear brutality was widespread in slavery, possibly approaching the norm, but we know from those same accounts that some masters did in fact think they were caring for their slaves as best they possibly could. Furthermore, as property, slaves represented a valuable investment, one that owners would be reluctant to abuse in a way that impaired their ability to function as the farm equipment of the early nineteenth century. Yet even as I considered this well-balanced, nuanced approach to American history, a part of me whispered in the back of my mind…

Who cares?

Blasphemous, I know. As a rule, I try to adhere to the school of thought that gives significance to every facet of history rather than that which demands justification for my time spent learning it. Yet here I took pause. Yes, this was a level of nuance likely accurate and not found in many accounts of the period. Laudable, in an academic sense, but as we continue to wrestle with the ideology slavery bequeathed to this nation, is that nuance necessary, or even desirable, for how we use history in the present? Is any attempt to ameliorate the horrors of slavery complicit in perpetuating racism, or at the very least in weakening the cause of antiracism?

As I tried to straighten out my feelings on these revelations, I was put in mind of another portrayal of “kind” slave owners, this time a visual one. In the course of Twelve Years a Slave, the Academy Award–winning film adaptation of the slavery narrative of Solomon Northrup, Northrup moves between multiple owners before finally regaining his freedom. One, played by Benedict Cumberbatch, seems at first to be a decent human being, the kind erased by abolitionists’ narratives. He listens to Northup’s suggestions, treats him fairly, and even seems to develop into a friend. So far, so similar. But when Northup capitalizes on this relationship to explain his wrongful enslavement (he had been kidnapped in the North and sold into slavery) and ask that his master free him to return to his family, Cumberbatch’s character completely folds. He never had any intention of treating Northup like an equal, like an actual human with civil and human rights; he was a favorite car, even a favorite pet, but nothing more.

This, I think, is how historians should approach nuance in antebellum slavery. That slave owners had an interest in treating their slaves well both to safeguard investment and increase economic output is true, yet in the same breath it should be noted that treating a person like a prized animal or trusty farm equipment is inherently dehumanizing—and the standards for caring adequately for an animal or vehicle are well below the standards for treating a human being with decency. Ultimately, I think our answer to these nuances should be the same as my answer whenever someone brings up the happy slave narrative: even under the kindest master in existence, these people were still slaves, their humanity and rights denied by other humans, bought and sold as chattel. That is inherent, insidious brutality you cannot write out of the enslaved experience and should always be the minimum takeaway of any such discussion.