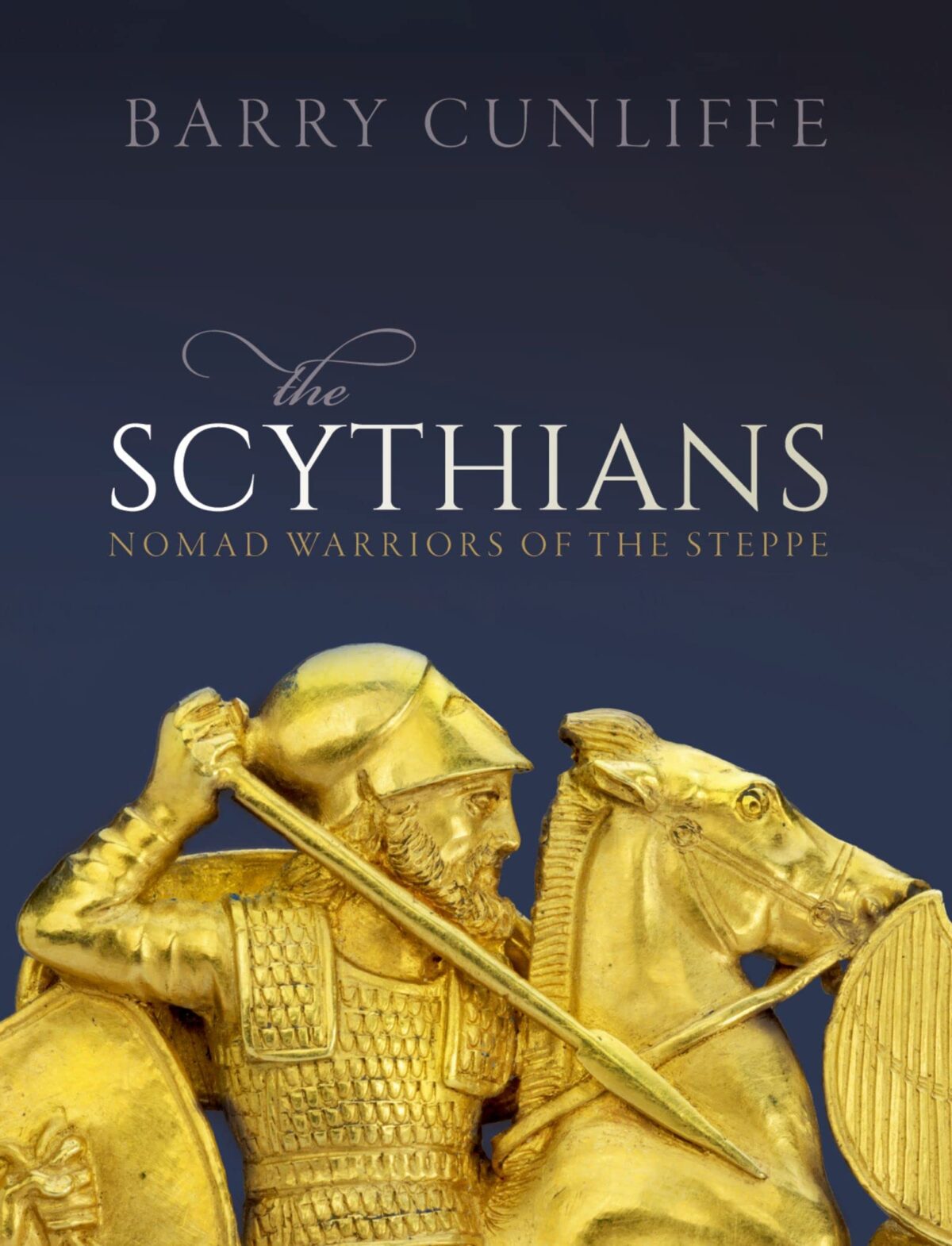

Cunliffe, Barry. The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

If you’re interested in any history before the early modern era, it is hard to avoid the influence of Central Asian steppe nomads. Whether it is the Xiongnu threatening Han China, the Huns pushing the Goths and Alans west against Rome before arriving themselves, the Turks taking over the Muslim World, or the Mongols getting close to taking over all Eurasia, the peoples of the steppe have been a major destabilizing and transformative force in pre-modern Old World history. I’ve often wondered at these successive waves of people from the seemingly-inexhaustible “Central Asian People Factory,” in my own words, but little did I know that my most recent foray into ancient history would give me exactly what I sought in the form of Barry Cunliffe’s historical and archaeological survey of the people known to history as the Scythians.

The Scythians main subject matter is its titular people, inhabitants of the European steppe north of the Black and Caspian Seas from the ninth century BC through the Classical Era until they were finally displaced by the Sarmatians (or Sauromatae) in the second and first centuries BC. They dance through contemporary sources, from killing the founder of the Achaemenid Persian Empire to Herodotus’ fascination with their customs to appearances in monumental Persian friezes as tributaries. Here Cunliffe thrives, dissecting history, social structure, material culture, and beliefs in as much detail as modern scholarship and physical evidence allows, accompanied by numerous beautifully-detailed pictures. I had originally been wary of such a history–ancient authors are notorious for their prejudices and fabrications concerning “barbarians” on the edge of the known world”–yet Cunliffe both recognizes the limits of our terminology (using archaeological culture names when appropriate) while also demonstrating that Herodotus and other Classical authors actually performed fairly reliable ethnographic research, sometimes on the front lines of cultural contact between the Greek colonies around the Black Sea and the Pontic steppe beyond.

Yet while the Scythians form the centerpiece of Cunliffe’s work, they by no means comprise its entirety, and The Scythians greatest value comes in the long historical perspective and context Cunliffe gives to the cultural continuum of the Eurasian steppe. His narrative in fact begins in the Bronze Age, a millennium before the Scythians’ arrival, demonstrating not only the continuity of material culture between different points on the steppe but explaining how the “steppe gradient” enticed movement westwards from the frigid, semi-arid step of modern Mongolia and Kazakhstan to the warmer, wetter steppe of modern Ukraine and Hungary. Climate changes, too, play a role, providing opportunities for steppe societies to contract, expand, and migrate in turn. Never before have I seen so clear a picture, or at least paradigm, for so much of ancient and medieval history.

If I can offer any critique of The Scythians, it is that Cunliffe’s organization can at times be more thematic than usual for a work of history, but this is minor at best, and indeed comes with many narrative benefits. I cannot help but wish Cunliffe had published this five years earlier than he did, as it would have been a perfect source for a paper I wrote on nomad empires during my time at Oxford. For those interested in ancient history, especially where the line between history and archaeology necessarily blurs, I cannot recommend this fascinating work highly enough.