“Make America Great Again.” These four words have become one of the most infamous phrases in the English language since the successful presidential campaign of Donald J. Trump, and with good reason. How do we define great? Who thought things were great? If we aren’t great now, when were we great, and when did we stop being so? Far from originating with Trump, this idea, that somehow the United States has lost its way from the glory of its just-out-of-reach past, has taken hold in the psyche of certain disaffected sections of its population. Though this reactionary sentiment may sound dissonant to the modern ear, it actually fits quite smoothly into a much longer historical tradition of cloaking nostalgic navel-gazing in terms of reform and progress.

“Make America Great Again.” These four words have become one of the most infamous phrases in the English language since the successful presidential campaign of Donald J. Trump, and with good reason. How do we define great? Who thought things were great? If we aren’t great now, when were we great, and when did we stop being so? Far from originating with Trump, this idea, that somehow the United States has lost its way from the glory of its just-out-of-reach past, has taken hold in the psyche of certain disaffected sections of its population. Though this reactionary sentiment may sound dissonant to the modern ear, it actually fits quite smoothly into a much longer historical tradition of cloaking nostalgic navel-gazing in terms of reform and progress.

The concept of progress or reform entailing the revision or rejection of past practices and creating new, better avenues for future improvement is a relatively recent anomaly. Any attempt to definitively date the genesis of this trend would inevitably invite endless debate, but I believe it can reasonably traced to the philosophies of Enlightenment thinkers. For most of human history the opposite has been the case. The instinct to reach longingly for a golden age of perfection and bliss can almost be said to be hard-wired into our human psychology. Numerous world religions begin or open the current age with tales of a lost paradise, where gods, humans, and nature lived in harmony and no one experienced want, shame, or sentience. The Abrahamic religious family is probably the most familiar incarnation of this trend, and Christian and Islamic efforts to gain admittance to paradise are assuredly the most common example of such nostalgic yearning.

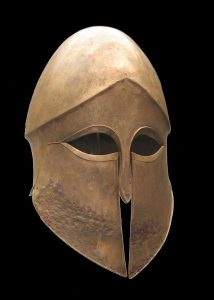

Religion is far from the only example of reactionary reform, however. Ancient societies in particular were rife with foundation myths and a fixation on recreating them. Land reforms in Confucian China continuously attempted to recapture the idyllic rural landscape of the early Zhou period, and Confucian bureaucracy was itself obsessed with applying a millennia-old system of philosophy to contemporary administrative work. Indian urban foundation and planning attempted to recreate legendary utopian cities, an impulse that spread alongside Hinduism and led to similar cities as far afield as the island of Java. Societies that emphasized military tradition proved particularly susceptible to this mindset; historian J. E. Lendon has proposed that Classical Greek hoplite warfare developed as an attempt to practically apply the principles of combat elucidated in Homer’s epics, while the fifth-century Roman historian Vegetius proposed military reforms that were really only an elegy for the past glories of Roman arms under the early emperors. In slightly more modern history, Martin Luther’s Reformation itself was an effort to return to the simplicity and devotion of only the Christian holy scriptures, rejecting the consequent baggage of a millennium and a half of Church tradition and dogma. The reality of these ‘golden ages’ of course could not have been quite so golden, but time only makes institutional memory fonder.

Though the modern era has offered increasingly fewer examples of such nostalgia-driven policy, it continues to cling to life in isolated pockets. MAGA is certainly one of them, as is the continued American fixation with using the ‘original intent’ of its founding fathers to guide legislative and judicial decisions. Whether humanity will ever totally break free of this instinct is impossible to say, and perhaps irrelevant. As we so often point out here at Concerning History, while history never truly repeats itself, it does inform every action and reaction we take. Nostalgic reform is the just the explicit tip of that massive influential iceberg.