With the seventh year of Concerning History now behind us, our staff takes the time to reflect on the major historical anniversaries of 2024. As it turns out, this year marks the anniversary of many interlocking suites of notable events, and we couldn’t resist taking the opportunity to talk about a broader swathe of history than we normally do!

1949: The Cold War Cometh

Bryan Caswell

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the advent of the geopolitical, ideological standoff that would come to define the later half of the twentieth century. The alliance of Great Britain, the United States, and the USSR during the Second World War was never quite a comfortable one, borne more from necessity and a common enemy than any shared values. Once the Third Reich had been defeated, then, the West’s wariness of Communism and the Soviets’ expansionism quickly soured their working relationship, and in June of 1948 Stalin made the first move, blocking off Western overland access to Berlin in an attempt to force its abandonment. Unwilling to back down, the United States and Britain supplied their sectors of Berlin exclusively by air for the next eleven months, and in May of 1949, the Soviets conceded defeat and lifted the blockade–though at the cost of formally splitting Germany into two independent nations, the German Democratic Republic (East) and Federal Republic of Germany (West). A month beforehand, in April, preparations were made for opposing Russia in the long term as twelve Western nations negotiated and signed the military alliance known as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

The West’s victory would not go unchallenged for long, however, and in August the Soviets would successfully conclude their first nuclear test; the enemy now had the A-bomb, severely complicating diplomatic and military considerations. As the battle lines solidified, America suffered its first major defeat when Mao Zedong’s Communists emerged victorious in the Chinese civil war and declared the People’s Republic of China in October, bringing the Cold War to East Asia and threatening Western colonial interests in the region while simultaneously increasing the importance of the occupation of Japan as a military base. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the rising world tension, the fight against Communism soon spilled over onto the American home front, and the infamous Hollywood Blacklist of suspected Communists was published that year as part of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s increasingly paranoid hunt for subversive agents. By the end of 1949, all the pieces were in place for what would prove a four decades-long struggle between two nuclear-armed superpowers and their respective allies for not only dominance, but which of their ideologies would prove most legitimate and beneficial for mankind.

Recommended Reading: The Cold War: A World History, by Odd Arne Westad

1774: Prelude to the American Revolution

Francis Butler

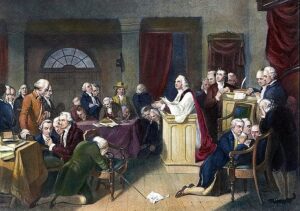

2024 marks the 250th Anniversary of some key developments in the British Empire’s political and constitutional crisis that led to the American Revolution. Between March and June 1774 Parliament passed, and King George III assented to, the Coercive Acts, a series of laws meant to punish the colonists of Boston and Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party. These acts terrified colonists throughout the Thirteen Colonies since they, among other things, dissolved Massachusetts’ colonial assembly and closed the port of Boston to all trade. Spurred on by exhortations from Massachusetts’ colonial leaders, delegates from twelve of the Thirteen Colonies met in Philadelphia in the fall of 1774 at the First Continental Congress. The delegates resolved to do three things: initiate a colonies-wide boycott against British goods, draft a final petition for clemency and negotiation to King George III (the Olive Branch Petition), and meet again in 1775, depending on the King’s reaction. By this time, colonists’ viewed Parliament with revulsion yet still hoped that King George III would intervene on their behalf against his wayward legislature. In reality, King George III was a hardliner when it came to colonial policy and was already inclined to view continued colonial protest against British taxation as a sign of outright rebellion.

Perhaps the most important result of the First Continental Congress was the actual charter delegates created to plan and enforce boycotts throughout the Thirteen Colonies. Some historians point to this document, called the Continental Association, as the de facto first constitution of the United Colonies (a designation the colonists used from 1774 to 1776). It set up a tiered system of governance that devolved authority for organizing and enforcing boycotts to each colonial assembly and then local governments. In fact, the Continental Association charged colonies and towns to establish Committees of Safety or Committees of Inspection to monitor colonists for any sign that they violated the First Continental Congress’s nonimportation, nonexportation, and boycott agreement. Colonists who violated these rules, or who even failed to show sufficient loyalty to the anti-British cause, faced communal reprisal. They could be beaten, tarred and feathered, branded, their property subjected to arson, paraded naked through their town square, imprisoned, or forced to flee their colony. Later on, during the actual war, Committees of Safety still operated and arrested Loyalists, but juries were often reluctant to condemn their indicted neighbors to death for treason to the Patriot cause. While 1773 may have begun the final to road to revolution, then, 1774 confirmed the colonists’ commitment to standing firm in defense of their rights as they saw them and developing the organizational machinery that would ultimately sustain the next decade of struggle.

Further reading: 1774: The Long Year of Revolution by Mary Beth Norton

1824: Creation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs

Heather Clancy

In July 1584, the first English foray into North American settlement landed on the future Outer Banks of North Carolina. There, 440 years ago, they made contact with the indigenous Carolina Algonkian–speakers whose Secotan tribe leaders would soon welcome them to Roanoke Island. A question no doubt emerged in those European minds as they watched foreign canoes glide toward them through the brine: Where did these russet-skinned natives fit into their white plans?

Fast forward through 240 years of tension, exploitation, and brutality, and we find a colonizer nation whose white citizens were still wrestling with that primordial question. For them, a partial answer came from the young American government: the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Formed 200 years ago in 1824 under the department of Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, the BIA would in 1849 be relocated to the Department of the Interior. In the years since, it’s undergone an agonizingly slow evolution from its original mission of cultural genocide to its purported current mission to assist and empower. In reality, the intra/international affairs the bureau governs continue to be strained. Not that you’d necessarily know from the BIA website—their version of events varies from We used to be the bad guys but we’re good now to We’ve always been the good guys, and please ignore the millions of skeletons in our closet.

Even considering the many other BIA anniversaries this year—the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the Tribal Self-Governance Act of 1994—and the slowly growing number of Native American representatives within the organization, I can’t help but look askance at a bureaucratic entity still in 2024 inherently operating in the interests of a white-dominated hegemony that continues to fail the colonized peoples it claims to protect. No “happy birthdays” for the BIA in this house.

In need of a pick-me-up? Here are some positive headlines in Native American news:

- “Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians buys city block at 301 Capitol Mall in Downtown Sacramento”

- “[Illinois] bill prohibiting the use of Native American names or imagery for high school sports teams and mascots being discussed in Springfield”

- “Why Indigenous Artifacts Should Be Returned to Indigenous Communities”

- “Biden-Harris Administration Takes Steps to Increase Co-Stewardship Opportunities, Incorporate Indigenous Knowledge, Protect Sacred Sites”

And a handful of recent indigenous successes on the screen and page:

- HBO’s True Detective: Night Country

- Apple TV’s Killers of the Flower Moon

- Apple TV’s Fancy Dance

- Stephen Graham Jones’s Indian Lake Trilogy

- Tommy Orange’s There There

Nick Medina’s Indian Burial Ground