In the second installment of his series highlighting some of the worst Supreme Court decisions in American history, Bryan explores one of the highest profile cases in the Court’s history, where it played the role of referee in the hotly contested election of 2000 in the ironically-explicitly-not-landmark Bush v. Gore.

The first presidential term of the third millennium AD was, perhaps fittingly, one of the most consequential for the course of twenty-first century American history. This has taken on even more significance in popular memory due to the highly contested election that gave us the presidency of George W. Bush. I was only seven at the time, but I vaguely remember the uncertainty and controversy that swirled around one of the closest Electoral College contests of the last century. Indeed, the election was so close that whoever won the state of Florida would win the entire election, and within Florida the two candidates were separated by less than 2,000 votes as the drama of election day and multiple waves of predictions, reversals, concessions, and retractions. The Election of 2000 would ultimately be decided in the Supreme Court, where it would see one of the worst abdications of democratic and judicial responsibility in the history of that body.

Despite the confusion of the night before, wherein most major news outlets had prematurely declared Democratic candidate Al Gore their projected winner based on faulty exit polling, there was a clear, albeit narrow, winner: the Republican Bush led Gore by 1,784 votes, less than .5% of votes cast and .01% of the state’s entire population at the time (it should be noted that Gore handily won the national popular vote, and that a report by the US Civil Rights Commission found evidence of widespread disenfranchisement in Florida during the election that particularly affected black citizens, though this was attributed more to incompetence and failure of preparation rather than malicious or directed policy). Florida’s Republican Secretary of State, Katherine Harris, announced Bush the winner of the state’s Electoral College delegates, but with such a razor-thin margin of victory, calls for a recount were inevitable. Perhaps understandably, Republicans viewed such a move with dismay, but an automated recount went forward, finishing two days later and narrowing Bush’s lead further, down to 1,457 votes–only to encounter a host of voting irregularities that complicated the issue still further. The use of a new kind of ballot (nicknamed “butterfly” ballots) combined with voting machine malfunction and user error had resulted in ballots that had either been undercounted (through the appropriate punch-out left hanging by one or more corners, the infamous “hanging chads,” or not only imprinted and not punched out at all, “dented chads”) or overcounted (through a vote for multiple presidential candidates recorded, and the ballot thus thrown out). These discrepancies, especially overcounting, were especially prevalent in four counties with a preponderance of Democratic voters and so, in accordance with a Florida election law that allowed candidates to request recounts in specific counties, the Gore campaign pursued a recount in those four counties, hoping to find enough votes to clinch the state.

The problem with manual recounts, of course, is that they take time, and time was the one thing Gore did not have. Florida state law mandated that all votes must be counted and certified by November 14, one week after the election, and Secretary Harris informed the affected counties that only votes certified by that date would be counted. None of them had completed their recount by the deadline, but four days later, a new hope emerged: in a 4-3 decision, the Florida Supreme Court declared that the spirit of the laws required all votes be counted, and so a manual recount of all votes in the state should be completed. Perhaps inevitably, such a controversial decision was appealed upwards by the Bush campaign, eventually reaching the Supreme Court itself. In Bush v. Gore, the Bush campaign argued that the ability to request a recount in some counties but not others, using different methodology than others, constituted a violation of Floridians’ equal protection under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, and that the Florida Supreme Court’s late decision was such a radical one as to constitute “legislating from the bench,” made even more egregious as only state legislatures have jurisdiction over election law. On December 11, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Bush on both counts in a 7-2 decision. Five of those seven justices declared that no recount could be completed in time for the December 12 “safe harbor” deadline for election certification nationwide, as a result confirming a previously-temporary stay on the recounts and effectively deciding the election in favor of Bush. Ironically, later studies of the ballots found that a manual recount that included undercounted votes would have likely led to the same outcome, slightly increasing Bush’s lead. Only through counting overcounted ballots–a measure the Gore campaign never requested–or rejecting all under-and overcounted ballots would have led to a Democratic victory, the latter by only three votes.

When I first began researching this case, my previous understanding led me to believe this was the most objectionable point of the resulting decision, but I could find no conclusive evidence that voting irregularities were only present in these four counties, and with all details on the table, I fully agree that the 14th Amendment had indeed been violated. I sympathize to an extent with the Gore campaign’s arguments that recounts in different areas can be necessary for different reasons and thus require different methods, and that mandating a single method across the board would render the principal of individual state control over election policy unconstitutional, but the ability to cherry pick one’s own recount cannot be sustained under any reasonable understanding of how democracy should work. “Legislating from the bench,” on the other hand, I’ve personally found to be a largely meaningless concept that is used by justices of all political stripes as a justification for overturning decisions they don’t agree with but cannot find other compelling legal precedent to overturn. Judicial decisions should be commensurate with what each situation requires, and sometimes that will require more sweeping or interventionist decisions than others; such is the nature of true judicial review.

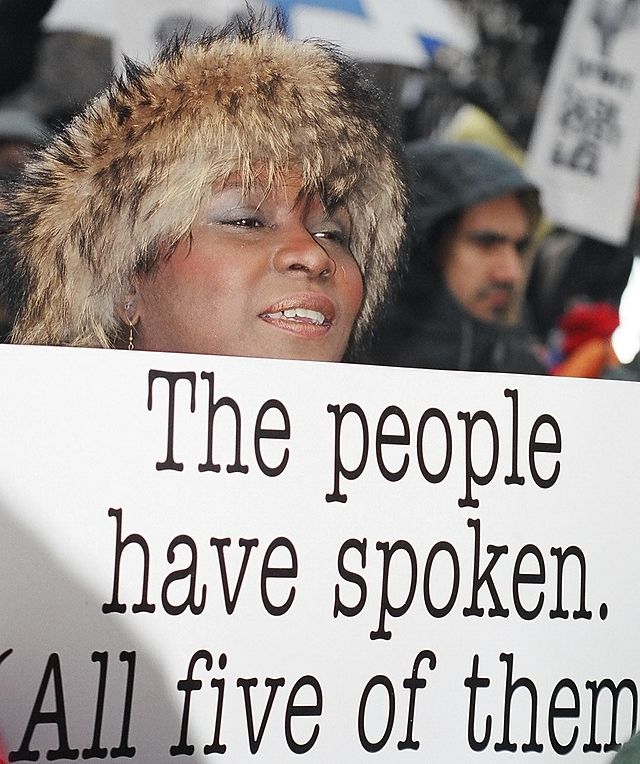

What really got me fuming about this decision was how dismissive of core tenets of democracy five of the nine Supreme Court justices seem to have been in their decision. In a presidential election that at the time of their ruling came down to less than 1,500 votes out of a nation of 282.2 million people, their response was to uncritically honor a bureaucratic deadline and just…stop trying. I cannot believe that a nation that so prides itself on its exceptionalism, innovation, and commitment to excellence could not have devised some way to at the very least conduct a proper, fair, recount–if not a redo of the whole election in Florida or the entire nation, moving deadlines and even inaugurations as necessary for such an unprecedented situation. A healthy democracy requires commitment and hard work at even the most basic, local level, let alone something as important as filling the office of the Presidency for the next four years, and this selection of ease over excellence was, in my opinion, a failure of our country’s core values.

Even more egregious, to me, was the Court’s admonition that this decision should not be considered legal precedent for deciding any future cases. This can only be read as an abdication of the purpose, role, and responsibility of Supreme Court decisions. Many in subsequent years have seen this move as one that recognized the decision’s inconsistent logic and apparently partisan nature, and I find it hard to disagree. The five justices that delivered the main decision were all appointed by Republican presidents, with the two dissenting justices and the two that agreed with the legal ruling but thought a recount was still possible appointed by Democratic Presidents. Of those five conservative justices, Clarence Thomas had ties to the Republican nominee through his wife Ginni, who was intimately involved with the campaign (history may not exactly repeat itself, but it sure does come close sometimes), while Sandra O’Connor and William Rehnquist had both expressed their desire to retire under a Republican president and dismay that they may need to postpone those plans (not to mention having been overheard at an Election Night party lamenting the election of Democrat Bill Clinton in 1992 as a travesty for the nation). It is difficult to escape the conclusion that in their chosen remedy, these justices tossed the election to their favored candidate while trying to guard against a similar situation in the future that could lead to the victory of an unfavored party.

It is hard to overestimate the impact of this questionable decision on the last two decades. It is tempting to question whether such watersheds as the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq or the 2008 housing crisis would have been so ill-handled or even occurred at all if a different man had been in the Oval Office from 2000 to 2008. That is a question that we can never know the answer to, of course (and may not even have been possible, given the likely results of the recount methods as described above), and I caution anyone who would think something so simple in the grand scheme of history could have led to a uniformly rosier future. What we do know, however, is that in the late autumn of 2000, five justices shrugged, said “Good enough,” and ultimately decided that it wasn’t really that important to gain an accurate assessment of who the American people had elected president. We deserved better.