One of the consequences of moving is reminding yourself just how many books you own that you haven’t read yet. In service of rectifying my own number, I’ve begun filtering old acquisitions into my lineup of reading material. One of those, Look to the Earth: Historical Archaeology and the American Civil War, has reignited one of my longest running personal debates. A conference of archaeologists arguing for the relevance and even basic existence of Civil War archaeology at first struck me as bizarre; I’ve generally resisted such gatekeeping that would challenge the existence of a field of study. And yet, the further into their papers I read, the more I really wondered: what is the purpose of historical archaeology? And, more importantly, what is the purpose of studying history in the first place?

Any undergrad student majoring in a liberal arts field has faced that dreaded question, both from others and from themselves as they prepare to go out into the world: “What are you going to do with that degree?” In a world where the STEM fields and visible “contribution” to our capitalist society, the humanities are consistently expected to justify their existence through appeals to utility. “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” we are often told, or the much shorter and easier to misuse “History repeats itself.” It doesn’t, really, but it is certainly true that one of the best ways to make more effective decisions in the realm of politics, economy, and general humanity is to understand why the world is the way it is, how past decisions have contributed to the present, and thus how to untangle the not of causation to build a better world.

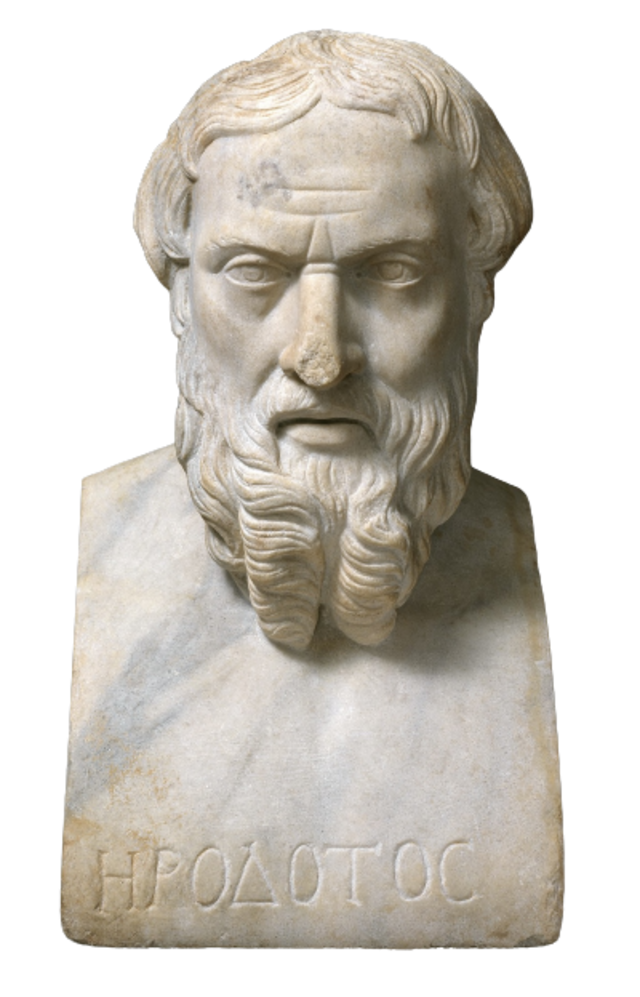

And yet, the vast majority of historical studies lie outside this consideration of utility or, as I often refer to it, “significance.” On a rocky hilltop overlooking the most famous battlefield in America, I once talked with fellow Concerning History staff member Kevin about how history is, at its core, a leisure-time hobby with no inherent practical value to society. While one can use history for secondary relevance, history’s primary purpose is simply to satisfy our curiosity about what happened in the past. Indeed, the word “history” itself comes from the title of Herodotus of Halicarnassus’ fifth century account of the Persian Wars entitled Historie–ancient Greek for “inquiries.” So many subdisciplines of history, both old and new, would fail any test of “significance” for modern life. The minutiae of battlefield tactics, the evolution of material cultures, even the histories of entire cultures and religions of sufficient age have little or no practical relevance to the twenty-first century. If one is applying such a test, Look to the Earth’s claims to help verify the details of battles or confirm the locations of shipwrecks do not go far in arguing for the field’s relevance.

As a practical, results-oriented thinker and as an avid collector abounding with curiosity, I frequently find myself torn between these two visions of history. In my very first post on Concerning History, I offered a partial resolution in my reflection on the role of chance in history: if nothing is inevitable and everything effects what comes after, then every detail of history is worth understanding in its own right, no matter how small and seemingly insignificant. And yet I am longer possessed of the starry-eyed exuberance of a liberal arts freshman, who is asked about the long-term prospects of a liberal arts degree and responds with a hearty “Who cares?” The prospect of spending tens of thousands of dollars in order to uncover a few hundred bullets or mark the location of a centuries-old ship that few non-specialists know the name of seems increasingly like a poor prioritization of resources to me, especially as the education system in the United States continues to deteriorate into a dystopian nightmare. I ultimately have no easy answers, and I’m sure I will have this internal debate again and again in the coming decades. Utility? Or curiosity, knowledge for knowledge’s sake? This dialectic won’t be going away anytime soon.