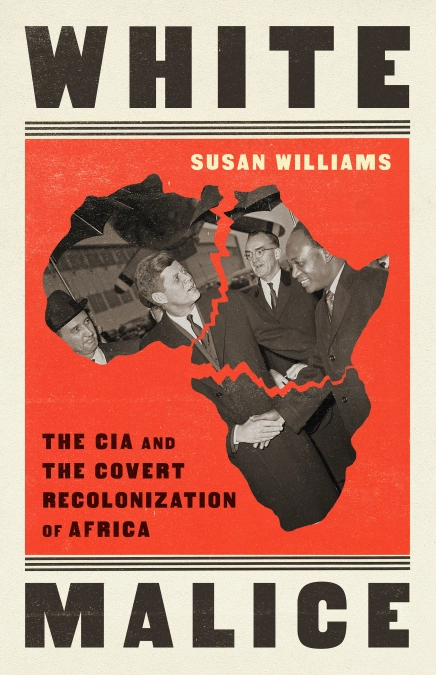

It’s time again for the Concerning History Book Club, where we recreate the experience of the engaging book discussions we’ve had throughout the years in classes and with each other. This month, Bryan and a friend review White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa, by Susan Williams.

Guest Contributor: When Bryan suggested we read White Malice by Susan Williams, it was the lure of front organizations and covert action in the Cold War that drew me back for another book club. I haven’t done much reading on decolonization in Africa, so the setting was new for me. It’s no secret that U.S. foreign policy in the Cold War was aggressive towards developing nations, and, at times, anti-democratic. I knew we did bad things, but while reading White Malice I was struck by how sterile passing comments about America’s history of toppling elected governments now seem. The story Williams tells is one much darker–and so much more personal.

BC: Even as someone who has studied this area, I agree. So many works on decolonization and neocolonialism are very dry and technical. Williams, however, gives us an eminently readable narrative that brings us into personal contact with the actual people these policies affected, and the dirty choices made on the ground level to undermine a democratically-elected government’s basic sovereignty. That said, I feel like it could have been even better. White Malice is very much framed as a popular history in the vein of Stephen Ambrose or David McCuloch; more narrative than analysis, and the reader is left to draw their own conclusions. With no intro, conclusion, argument, or analytical framework, Williams’ work can go only so far towards doing what I feel a truly great history of her subject should. Even the title could use improvement, as it seems to promise a much more comprehensive treatment of African de- and re-colonization than her narrative actually delivers.

GC: I didn’t notice the lack of an introduction while reading it–the title alone seemed to capture the argument so well–but I assumed my confusion about the narrative’s direction was due to my limited experience with the literature. Now that you point it out, though, I think any reader would be helped by a clearer roadmap or signposting about the interconnectedness of her narrative.

BC: And that lack of a roadmap can even lead to WIlliams’ narrative itself seeming unfocused or, ironically, too focused at times. I often found myself both intrigued by the section I was reading and puzzling at its relevance to (what I perceived to be) White Malice’s core subject matter. On the other hand, Williams often did not discuss topics that seemed to be important, even necessary, to show her topics in their full light. Most noticeable was how she treated Western fears of Communist influence in Africa. Rather than examining the source of those fears and if they had any validity, Williams largely does not talk about them, seemingly arguing that these fears were baseless by simply not giving them any attention. This had the opposite effect on me; I began to assume that Williams was massaging the narrative to fit her intent of painting a damning picture of United State policy, especially when the Soviet Union kept coming off as, at best, well-meaning partners or, at worst, impotent minor players.

GC: For context, the book ties together a lot of examples of US influence in African politics, primarily by funding academic and cultural front organizations, cultivating opposition leaders including Joseph Mobutu, sponsoring visits by US celebrities like Louis Armstrong, and exercising influence at the UN. But the main narrative is how the US undermined Ghananian President Kwame Nkrumah’s vision of pan-Africanism through direct interference in the Congo’s transition to independence.

I agree that the dotted line these connections require could have been made more explicit. Fundamentally, though, I think Williams is interested in showing how the US had the means, motive, and opportunity to act as she alleges. She demonstrates that the US was more than willing to use both hard power and soft power (perhaps more accurately sharp power). That the US government is so intent on using seemingly excessive and redundant strategies reflects its self-awareness of the hegemonic power it wields.

You mentioned how the Cold War disappears into the background more than it should, and I think that’s a fair argument, but I’m struck by the extent to which US officials treated geopolitical considerations almost as an afterthought once decisions were made. There wasn’t much space to reconsider the situation. Once the US government determined the Congo’s Patrice Lumumba had the wrong friends, it simply decided it didn’t like him and that was enough reason for moving against him.

BC: Couldn’t agree more, and thus the title, What Malice. It felt almost petty, like the US was acting like a group of mean girls in high school–except instead of policing cafeteria seating, they’re assassinating elected heads of state based on no more than personal dislike. I’ve always thought of the Cold War as an exercise in realpolitik, when the demands of modern statecraft conflicted with the lofty founding principles of our nation. Yet that only holds true if those actions were truly demanded, and Williams’ narrative calls that into serious doubt. The CIA at times comes off as a bunch of blind loons, pumping millions of taxpayer dollars down the drain to finance ineffective intelligence operations and ever-more-cartoonish plots, all without any semblance of democratic oversight at the time. Even this long afterward, I felt deeply uncomfortable as an American that these things were being done in my name, without my say so.

GC: We’re talking about this in the past tense, but Iraq 2003 came immediately to mind. What accounts for this astounding and fatal incompetence? I can’t explain non-existent WMDs, but in the 1950s the CIA was still a relatively young agency. Its leaders were building the airplane while flying it. This was especially true in Africa, according to Williams. And the Agency does not appear to have internalized the message “With great power comes great responsibility.” I wonder the extent to which the failings in Africa were bound up in varying levels of ignorance, indifference, and racist contempt.

BC: As do I. Even though this was the first generation of American statesmen to have traveled globally in their younger years, the nature of that travel is telling. Eisenhower in particular served in the Philippines and Panama before his command in Europe during the Second World War–both of which would have seen him essentially playing the role of imperial constabulary, a position not usually conducive to multicultural understanding. I also wouldn’t be surprised if the empty confidence of the early CIA also came from its composition of entirely affluent white men; the same phenomenon that still sees white men apply for jobs that they lack qualification for may have resulted in the early Agency doubling down on vague rumor or unreliable informants as absolute fact. Despite my early misgivings, if even half of what Williams relates is true, there really is no other word for all this than damning

GC: All together, Williams paints a picture of American insidiousness. She tells a story of neo-colonialism, giving lie to the idea that post-colonial Africa emerged autonomously with minor interventions from a benign West. She asserts that the US was systematically involved in the infiltration of both business and civil society, and provides a direct link to even more aggressive and deadly means of influence that killed a democracy and left a violent dictatorship in its wake. For the US to rally the democratic world against rising authoritarianism, we need to grapple with our own role in its proliferation–and ensure the challenge of China and Russia does not push us to repeat our mistakes.