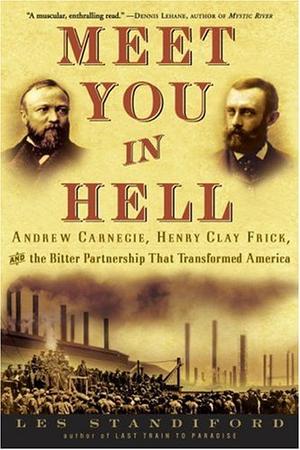

Standiford, Les. Meet You in Hell: Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and the Bitter Partnership that Transformed America. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2005.

I have sometimes remarked to friends, among them my fellow staff of Concerning History, how dismaying it is that the Gilded Age is not taught more engagingly in modern history curricula. If ever there was an era of American history with relevance for the 21st century (other than, of course, the Civil War and Reconstruction), it would be the half century surrounding the turn of the 20th where vast fortunes were made by the privileged few on the backs of exploited immigrant labor as that same labor fought to unionize and improve their treatment. Instead, students are almost invariably treated to just another litany of terms and people. Leave to a novelist, then, to really bring the period to life in all its gritty detail.

Les Standiford’s Meet You in Hell tells the story of Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick, two of the biggest titans of industry to come out of the 19th century (and it’s not just my Western Pennsylvanian pride saying so). In vivid detail, Standiford conducts readers through these men’s rise from poverty, initial business forays, and ultimate rule over the United States steel industry. Front and center in this narrative is the infamous Homestead Steel Strike, when Carnegie’s desire to depress wages combined with Frick’s disdainful attitude towards labor led to violence and dozens of casualties between striking workers and privately-hired Pinkerton Guards. Standiford tells his story with admirable nuance, giving Carnegie, Frick, and their compatriots balanced consideration while also making clear the economic plight of their laborers. The tragic failure of the strike is made all the more so by the heights of wealth to which both men would rise over the following decades and the utter lack of accountability for their decisions– something not unusual for their age.

Standiford’s narrative is not without its problems, however. Aside from a few stumbles early on (such as a laughably incorrect date for the first historical production of steel and opening in 1919, then stating the intention to start in 1892, then immediately afterwards actually starting in 1848), Meet You in Hell is suffused with a sort of false consciousness from Standiford, himself the son of mid-20th century Ohioan factory workers. He makes explicitly clear his admiration for an America in which anyone, even penniless immigrants like Carnegie and Frick, can make it to the very top of the socio-economic pyramid through their own hard work. And yet, Standiford’s own narrative shows the lie in his framework; both Carnegie and Frick’s early successes may have been sparked by work ethic, but were mainly fueled by personal connections and, in Carnegie’s case, insider trading–the very opposite of the “American Dream.” Telling, too, in this context is Standiford’s failure to even implicitly call Carnegie out on his passionate belief in Social Darwinism, a bankrupt ideology from the moment of its inception. It is also evident that too often in this system, the individuals who rise to the top are more predators than people, and it is the ceaseless wrangling for position and wealth between these two robber barons that led to their final acrimonious falling out, not the legacy of Homestead as Standiford would have his readers believe.

If armed with a firm sense of analytical thinking, however (or at least a good critical reading guide) readers can find significant value in Standiford’s prose. I’ve seldom seen the intricacies of Gilded Age business so clearly and compellingly described, and the events that took place at Homestead (and other locations) deserve to be more widely known in their proper context. I may even begin using it with my own students–in highly supervised fashion, of course.