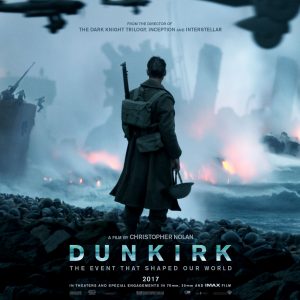

Last Thursday we had the great pleasure of seeing Christopher Nolan’s new film Dunkirk. Chronicling the events of Operation Dynamo, the evacuation of British and French forces from the beaches of Dunkirk after they had been beaten and surrounded by German forces in 1940, Dunkirk is a war movie unlike any we have yet seen.

Last Thursday we had the great pleasure of seeing Christopher Nolan’s new film Dunkirk. Chronicling the events of Operation Dynamo, the evacuation of British and French forces from the beaches of Dunkirk after they had been beaten and surrounded by German forces in 1940, Dunkirk is a war movie unlike any we have yet seen.

Dunkirk is of course not a documentary but a fictional retelling. Despite this, never have we seen a movie that so eloquently and (mostly) unobjectionably captured the spirit, general facts, and significance of an historical moment. Dunkirk splits its story across three narratives that cover different facets of the whole: a group of young soldiers on the beach; a father, his son, and his son’s friend taking their pleasure yacht across the Channel to help any way they can; and a fighter pilot attempting to keep the skies clear for the rescuers. Through this personal yet representative touch, Nolan is able to tell his fictionalized history with minimal resort to any overt fudging of real events. The most initially striking aspect of these narratives and the story as a whole is its Britishness; not only did Operation Dynamo occur before the United States’s entry into the war, but the themes and mythmaking inherent in both the movie and the history are present more generally within British culture as the celebration of stoicism and duty in the face of grave adversity. In Dunkirk, that adversity is especially pressing. The 400,000-strong Allied forces at Dunkirk faced annihilation at the hands of the advancing German armies, but in this movie those foes are never intimately present. No face of a German soldier is ever seen. Indeed, in the first of many unique stylistic choices, no German soldiers are even seen on screen save for a brief scene at the end. In the implacable machinery of planes and torpedoes and in the omnipresence of the enemy beyond the Allied perimeter there exists not so much an adversary as an existential dread that permeates the entire film. This effect is compounded by Hans Zimmer’s insistent, literally-clock-ticking score that, while a bit crude, certainly ramps up the tension. There is admittedly sparse characterization of any of the players involved, and though for some this might mitigate some of that tension, for us this deliberate effort served to emphasize the basic humanity involved in the subject matter: no other knowledge is needed to care about these men’s survival. Indeed, like with the German forces, the faces of the dead are never seen except for one civilian. Aside from all its loftier successes, Dunkirk possesses a realism derived from the extensive use of practical effects. Its aerial choreography in particular is thrilling, and even small details like the inclusion of Black French African soldiers serve to round out the historical setting.

As alluded to above, Dunkirk is not your typical war movie. Some of this must stem from the outcome of the event itself: while in many ways a triumph, the military campaign concluding in Operation Dynamo was decidedly not a victory. Instead, base survival is seen as an achievement. Along with and contributing to its dual-facelessness, Dunkirk offers sparse dialogue as its characters behave with refreshingly non-expositional veracity. There is also extremely minimal blood and gore, and while it adds yet another intriguing aspect to the film’s atmosphere, Nolan’s intent here is difficult to discern. In other ways, however, Dunkirk is very traditional. The ultimate message is one of hope and (re-defined) victory, symbolized by Kenneth Branagh’s unfailingly noble Commander Bolton and the selfless actions of Britain’s civilians. Tom Hardy’s pilot storyline is also fairly standard, and while his somber persona isn’t exactly the cocky archetype, his actions in burning his plane and surrendering fit into the trope of prisoners-of-war reclaiming their agency.

As magnificent as Dunkirk is, it still has a number of flaws. Most noticeable is its slight narrative confusion. It attempts to accommodate themes of both hope, mentioned above, and a primal struggle for survival which, while obviously present side-by-side in any number of historical events, is difficult to achieve in a story without muddling its telling. Thus to some Kenneth Branagh’s performance may seem jarringly romanticized, while others might find the main band of soldiers’ litany of shirking, desertions, theft, and attempted murder oddly deplorable in light of the abounding spirit of selflessness. Second, the film contains very few women, and all are rather two-dimensional nurse/mothering figures. Possibilities to include women within the confines of historical accuracy are naturally limited in portrayals of certain eras and events, and Dunkirk’s avoidance of the “sweetheart back home” trope just eliminates more of them. The depiction of the French could also have been better. Though they are mentioned and in one scene shown to be defending the perimeter, keeping the evacuating British safe from the German ground forces, a more explicit admission of their heroism would have been welcome rather than the appearance of being reluctant allies or even at times openly subversive. Other objections are more technical; Nolan’s decision to spread his three overlapping sub-narratives out over different chronological frames, though a compelling storytelling device if understood, could have been initially explained better and might result in audience confusion as a result. The opening scene, which serves to isolate the main soldier character, also feels weirdly executed and out of place in larger context.

Despite these reservations, Dunkirk is well worth viewing. Not only is it a (perhaps relatively) superb example of historical movie making, but its general lack of explicit content in violence and in language makes it uniquely suited to be an interpretive tool in the classroom, be it high school or college. We can only hope that its gripping account of such a pivotal struggle in the Second World War can not only lend increased exposure to the events themselves but encourage American audiences to learn more about a conflict that stretched so much further than our own involvement in it.

2 replies on “Humanity in the Face of Annihilation: Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk”

Just saw the film. Wonderful review, thanks for writing. I would slightly disagree that women were relegated to only traditional (i.e. nurse) roles. I was surprised and pleased to see several civilian women on board various yachts.

I have been anticipating this film since I saw the teaser for it (one of the most well constructive and effective teasers I have ever seen), and I did enjoy it. I was disappointed by the score as I believe a more melodic score could have been just a effective, but that is a personal thing. I too was pleasantly surprised to see civilian women among the small boat force however, I also would have appreciated it if there had been a more main female character. The son on the pleasure yacht could have been a daughter, for instance.

I have mixed feelings on the treatment of the French. While on the one hand it is important to acknowledge their heroism, I feel for this film their story doesn’t have the right tone. There were not very many examples of “heroism” as we are used to seeing them on the big-screen battlefields but rather examples of everyday heroism; heroic actions performed as a course of duty/occupation or life-saving actions that were undertaken with little/no risk to the person performing them. To me this made it more relatable for the audience, in the same way that the casting of mostly unknown actors for the characters with the most screen time does (brilliant decision in my opinion).