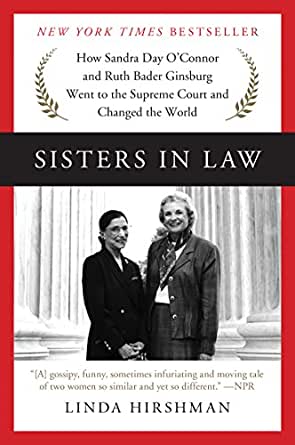

Hirshman, Linda. Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World. New York: HarperCollins, 2015.

The past decade of American politics has vaulted the Supreme Court into the public eye like no time since perhaps the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. From contentious decisions on both sides of the political aisle to hard-fought nomination battles, it feels like an ever-growing number of people look to the Court and its nine justices as the final arbiter of the American way. That said, even as I have grown increasingly familiar with the Court’s decisions past and present (AP Government coaching for the win), I have not gained similar familiarity with the actual people who have filled its bench. Thus, when my parents sent along Linda Hirshman’s dual biography of the first two women to sit on the Supreme Court, I was intrigued. While I may not have gained what Hirshman intended from her work, I still count it as one of the more valuable books I read in 2019.

Sisters in Law proceeds in the tradition of Plutarch’s famous series of parallel biographies, telling the intertwining story of two of America’s feminist pioneers as they built their careers and finally found themselves appointed to the highest court in the land. One was one of the least likely candidates one could imagine to first break through that glass ceiling: a conservative Republican, proponent of traditional gender norms, and never previously a Federal justice at any level, would go on to be nominated by Ronald Reagan as the first woman Supreme Court Justice and become a voice of moderate jurisprudence for decades. The other, a liberal Jewish woman and icon of the feminist movement, would arrive a decade later and become a symbol of gender equality and speaking truth to power.

As one might surmise from Hirshman’s subtitle, Sisters in Law is not meant to be any kind of hard-hitting analytical history. The lives and accomplishments of both O’Connor and Ginsburg are related in terms that can only be described as glowing, if not fawning. Indeed, certain moments seem incongruous; O’Connor’s lack of coherent legal philosophy and willingness to decide in a way that avoided rocking the boat and simply kicked the consequences down the road deserves intense scrutiny, not faint praise.

Even as I trekked through O’Connor and Ginsburg’s respective apotheoses, however, I was fascinated by the culture laid out before me. Earlier, I mentioned that I consider Sisters in Law to be one of the more valuable books I read in 2019, and I meant it, though not necessarily in a positive manner. As I read about the backroom deals, the process of deciding cases, the outspoken opinions of the justices and the methods they used to gain their desired outcome, I finally saw the Supreme Court for what it was and is: not an august, impartial body that checks the partisan schemes of the Executive and Legislative branches, but a body of nine politicians no less biased than any other.

While this revelatory disillusionment is certainly not found solely in Hirshman’s work, Sisters in Law certainly presents an approachable and engaging vector for it. Whether you are looking for context for either of Hirshman’s subjects, the legal battle for second-wave feminism, or the Supreme Court itself, Sisters in Law certainly fits the bill.