As I began researching my new series on utterly stupefying Supreme Court decisions throughout history, I began coming across a number of cases that did not sit right with my modern sensibilities, yet still possess consistent internal logic in the Court’s opinion–albeit in service of a worldview that I partially or entirely reject. Many of these decisions reveal unsavory truths about our country and how the legal interpretation of its founding principles have evolved throughout the centuries. Coming to grips with the issues at stake in these little-known cases and the questions they pose for the nature and expression of our democracy–and so a second, parallel series was born! In my first installment, I tangle with how surprisingly racist the very foundations of United States naturalization law have been, from the very beginning.

Back in January, Republican presidential candidate Nikki Haley (herself of Punjabi Sikh heritage) made waves when she claimed that America “has never been a racist country.” While she further qualified that statement over the ensuing weeks, that general sentiment is one that worrying numbers of Americans uncritically cling to. Any halfway-serious student of history knows just how ridiculous it is to claim that the United States, a country that enshrined race-based slavery in its founding Constitution as it expelled indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands and later prohibited immigration by entire race-defined populations, was never racist. I couldn’t help but recall Haley’s comments, though, when I discovered a detail of just how discriminatory our country’s immigration policies were from the very beginning.

In 1790, just three after the ratification of the new Constitution and one year into the first ever session of Congress, Federal lawmakers passed the United States’ first ever Naturalization Act. Among other details of policy like providing for the citizenship of individuals born to American citizens while abroad, this act clarified the process of an alien becoming a citizen of the new nation: after living in the United States for two years, any immigrant could petition a Court for citizenship upon demonstration of “good behavior” and taking an Oath of Allegiance…if they were free and white.

This is not a comment on the practical realities of how the law was implemented. The Act of Congress explicitly states, in its very first sentence, that only free, white individuals could become naturalized citizens of the United States. This really shouldn’t surprise anyone familiar with the intellectual climate of the 18th and 19th centuries, but I was shocked at just how long this policy remained on the books. While subsequent modifications would adjust the length of the residency requirement and other niceties, an explicit ban on nonwhite naturalization would last until 1952. In those one hundred and sixty-two years, the only substantial legislative attempt to do away with this came, fittingly, from Radical Republican Charles Sumner during Reconstruction. The 13th and 14th Amendments to the Constitution had done away with slavery and provided for birthright citizenship regardless of race, respectively, and Sumner proposed the next most logical step: providing for anyone to become a citizen regardless of race or point of origin. Unsurprisingly, however, this amendment never even made it to a vote.

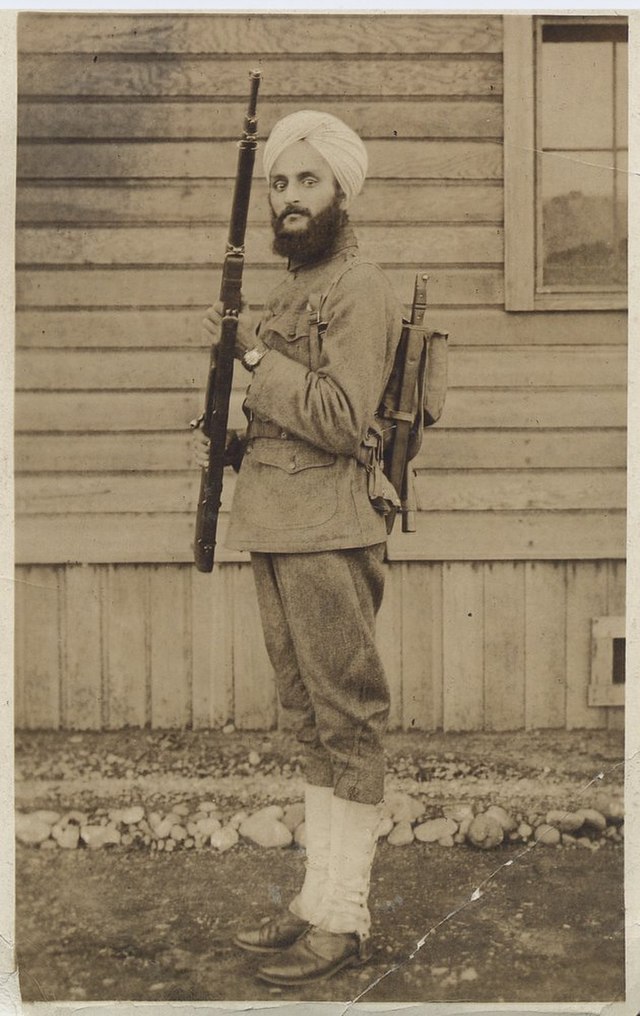

As the country became increasingly integrated into the wider world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, this racist naturalization policy came under increasing scrutiny, culminating in two Supreme Court cases only one year apart. In 1914, a Japanese man named Takao Ozawa applied for citizenship in Hawai’i and was denied. He had been living in the United States for twenty years, spoke fluent English, attended a white Christian church, graduated from UC Berkeley, and both his children were citizens. Finally, in 1922, his case reached the Supreme Court, only to be struck down. Justice George Sutherland conceded that skin tone varied greatly amongst ethnic groups, and so a simple color test was insufficient for determining naturalization, but set the bar at being a member of the “Caucasian race.” One year later, in 1923, the Court heard the appeal of Bhagat Singh Thind, a Punjabi Sikh man who had served in the US Army during the First World War and had applied for citizenship on the basis of identifying as Aryan, which by some definitions would make him Caucasian. Ironically, if predictably, Thind was turned down as well, with Sutherland now making it clear that Caucasian needed to be “properly understood;” that is, you needed to look white, too. Happily for Thind, a New York state law providing for citizenship for First World War veterans regardless of race allowed him to eventually naturalize in 1939–two decades after his initial efforts. Thind would go on to earn PhDs in theology and English literature, becoming a lecturer in metaphysics and spirituality.

Thankfully, the United States no longer bars people of color from even the possibility of citizenship if they were born outside the country, but the fact that it did so for such an extended period of time, and this principle of racist naturalization exclusion was upheld in not one but two Supreme Court cases, demonstrates just how prejudiced our nation has historically been. It bears noting that Nikki Haley is of Punjabi Sikh descent, just like Bhagat Singh Thind, and if her parents had immigrated to the United States just twenty years earlier, they would have done so with no prospect of ever gaining citizenship at the time. We’ve made great strides in more fully realizing our country’s initial egalitarian promises (with significant work still to go), but we forget how far we’ve come at our own peril. Those that claim that the United States was never racist do so by ignoring its–and in some cases, their own–history.