Recently, I finished reading two stellar books concerning key moments in Modern European and American History. The first was Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy by Eric Weitz and the other was The Thin Light of Freedom: The Civil War in Reconstruction in the Heart of America by Edward Ayers. While each book concerned vastly different topics and events, there were some startling parallels between the epochs covered in these two monographs, namely, the ways in which reactionary political movements in both interwar Germany and the Reconstruction South demolished the rights of minority citizens and heralded the rise of vindictive authoritarian regimes in both Germany and the United States. Today’s post is the first of two that will analyze similarities in the establishment of the post-war democratic societies in both Germany and the South.

Now, this comparison of Weimar Germany and the Reconstruction South is a rather bold claim, so context is important. Both Weimar Germany and the Reconstruction South were societies born from old systems of privilege and labor that had been dismantled through defeat in a devastating war. For the Reconstruction South, chattel slavery and the cash-crop capitalism of the antebellum era fell apart in 1865 as Union armies brought emancipation and land redistribution (temporarily) to the South. Germany in 1918 saw the rise of a working class in the military, urban centers, and rural towns determined to assert their demands for relief from the Prussian military’s autocratic mismanagement, an essential end to noble privilege, and a revision of the military’s role in civic society. In the wake of these upheavals, only made possible by defeat in the Civil War and the First World War, respectively, both the Reconstruction South and Weimar Germany were forced to accept a series of political compromises which ushered in democratic government and protected the rights of minority citizens. In the South, this meant that Southern state governments had to ratify constitutional amendments which ended slavery, guaranteed the equal protection of the laws and citizenship for freedmen, and extended the right to vote to Black men, a key number of whom were Union veterans or Northerners who came south to help build a new democratic society. For Germany, democracy meant the adoption of the most liberal constitution present in the Western world, which protected the rights of workers and extended the franchise to women in 1918. It also enabled freedom of speech and established a more uniform and competitive process for elections. These were political revolutions inconceivable even five years prior to their adoption, forced or otherwise.

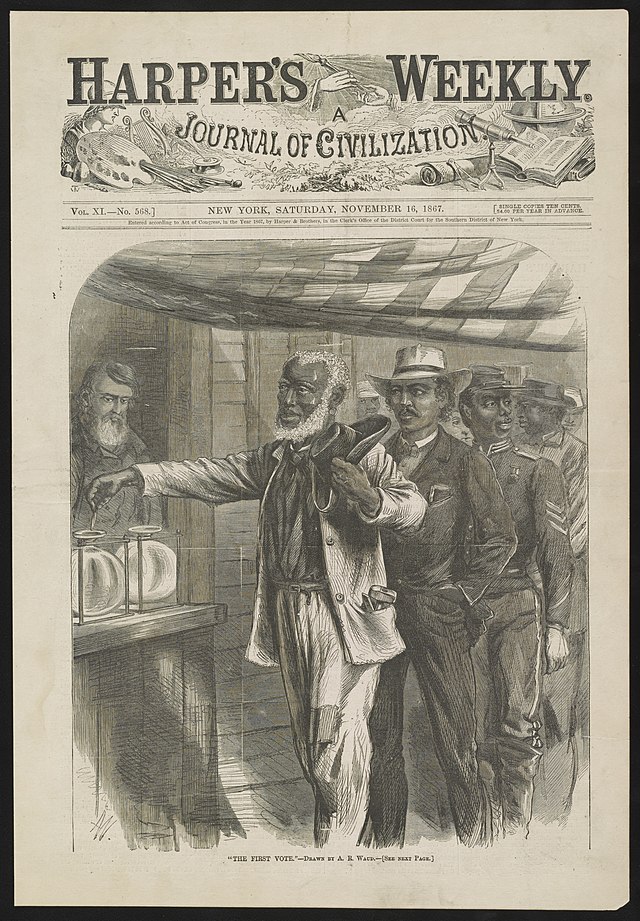

For a period of time (about five years for both), the Reconstruction South (1867-1873) and Weimar Germany (1923-1929) had functioning democratic societies. In the Reconstruction South, Black men were actually able to vote and participate in elections at the state and national level. Coalitions of Southern Black men, white Unionists, and Northern transplants elected Reconstruction governments and even sent Black representatives to the House and Senate in D.C. In Weimar Germany, the Social Democrats, the nation’s equivalent of a center-left party, dominated a robust welfare and pro-labor state that kept together a loose coalition of democratic-leaning parliamentarians with the Catholic Center Party. What is remarkable about these two societies is the ways in which they actually worked. Fringe groups, be they virulent former Confederates, Fascists, or Communists, were kept out of power or even suppressed (hurrah for President Ulysses Grant!) and the economies in each region, while not perfect and still exploitative of working class or Black laborers, slowly recovered from the devastation of war.

Markers of this change were found in the political and cultural achievements of the Reconstruction South and Weimar Germany, too. For the South, ushering in a new era of civil rights and economic repair, the presence of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the growth of a Southern Republican Party vastly changed the political and cultural landscape of the late 1860s and early 1870s. Now, Black men, some of whom were armed, and their white allies, working class and yeoman whites as well as a few elites such as the former Confederate General James Longstreet, worked alongside Northerners to usher in reforms. Schools were built and manned by Northern missionaries, new cities or hubs of manufacturing were created to industrialize the South, and military governorships run by Union generals presented former Confederates with a clear and present reminder that their states were only able to be readmitted under strict conditions set by Congress. For all intents and purposes, the enfranchisement of Black men, and the growth of Republican politics in the South, was a heretofore unanticipated and unrivaled victory for the Republican Party — in the heart of enemy territory, the G.O.P. had built a durable alliance of Black sharecroppers, Black veterans, Northern Black transplants, Union veterans, and working class Southern whites to counteract the white supremacism and anti-Union sentiment of former Confederates, especially in states such as Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida that had significant populations of Black people.

In Weimar Germany, the political transformations brought about by its constitution, coupled with the liberalization of society that the new constitution enabled, led to new forms of art and self-expression unknown in Germany prior to the First World War. Modernist architecture essentially found its birth in Weimar as a generation of new architects and engineers, seeking to break from the traditionalism of Germany’s imperial architecture, used their building projects as markers of Germany’s break from its history and emergence as a new nation and people. Shopping malls, apartment buildings, business parks, and scientific institutions all used the sleek lines, windowed facades, and boxy-to-curvy designs of modernist buildings. Gone were the Gothic beer halls or Classical buildings; instead, the modern era and its new ideas of democracy and progress were embodied in buildings themselves.

More importantly, Weimar also carved out a place for women (and, in some cases, Germans in various types of same-sex relationships, mostly in Berlin). Weimar’s constitution conferred on women the right to vote and wartime economic policies (and male casualties) expanded opportunities for the “new Woman” to enter the workforce. There was also a movement to culturally and scientifically improve society through better sex — one that saw physicians and psychologists travel Germany and explain that sex was not only about the couple, but an act that had a social (sometimes Christian) and political purpose. The core idea behind these “better sex, better society” discussions was one of mutual equality between husband and wife (or lovers in the case of those who spoke to and wrote for same-sex couples). Some reformers even advocated for this sexual revolution as a precursor to further political revolution. Their formula was to say that once men treated women as equals during sex, society would transform to fully recognize the exploitations of capitalism and reform, reverse, or overthrow those abuses (depending on how radical the reformer was). There was even a self-liberation movement that emphasized the virtue of nudity in nature which garnered support from across the German political spectrum. (In fact, one of the leaders of this nudist movement named Hans Suren wrote a rather homoerotic book about the need for young German men to be naked and in the sun together. His ideas caught on with many and included many photographs demonstrating how to be naked in the sun. Later, he rewrote his most popular work to include Nazi racial ideas and became a party hack and fitness coach).

However, in both the cases of Weimar and the Reconstruction South, such revolutions in political, culture, sex, gender roles, and architecture were all predicated on the democratic reforms that both societies adopted out of expediency. For the South, the political and cultural reforms which enabled Black men to vote, led to the creation of Southern Republicans, and saw the abolition of slavery and the enfranchisement of Black people were all the preconditions the South had to meet to rejoin the Union. In Weimar, the new modern, democratic, and more-socially-equal state which replaced German nobility, hierarchy, militarism, and privilege all stemmed from the agreements Germany accepted in the hopes of negotiating a better peace settlement at the end of the First World War. Neither had extensive depths of support in their societies and, if faced with political and cultural counter-revolutions, economic catastrophe, or inconceivably both at the same time, the health of these vibrant, budding multicultural democracies might prove to be poisoned in the cradle.