by Bryan & Heather

We can still remember one of the most contentious class debates from our undergrad years. It was time to discuss the road to the Second World War in Modern British History (one of the few classes we took together in college), and Dr. Isherwood presented us with the thorny issue of the Munich Conference of 1938 and Allied appeasement of Nazi Germany. Almost universally maligned since nearly the outbreak of the war only a year later, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s infamous decision to force Czechoslovakia’s cession of the Sudetenland to Germany has been seen as the act of, essentially, a coward unwilling to stand up to an international bully (who we now know to be an international villain of the most dire caliber). The question Dr. Isherwood posed to our class, though, was whether Chamberlain had prevented war through his actions. Most of the class scoffed, thinking this was an absurd question; of course he didn’t! Just look at the history books! Bryan, however, feeling a bit of the devil’s advocate, replied in the affirmative. Chamberlain might not have prevented what we know as the Second World War, but as of the moment of the signed agreement in Munich, he prevented the war that would have broken out at that moment. Almost a decade later, enter the Netflix film Munich: The Edge of War.

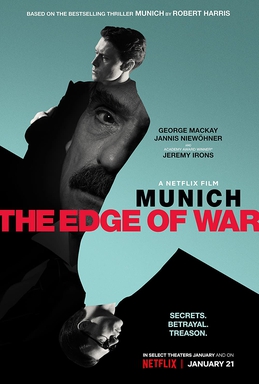

Based on the George Harris novel Munich, Munich: The Edge of War relates the fictional story of Oxford chums Hugh Legat, private secretary to Chamberlain, and Paul von Hartmann, a German diplomat and secretly a member of the conservative German resistance to Hitler as they attempt to prevent the Munich settlement and reveal the Nazi regime for what it truly is. The crux of the plot centers on the Munich conference itself, as von Hartmann desperately tries to smuggle a document to Legat containing minutes of a meeting wherein Hitler and his lieutenants outlined their plan for European domination that would not stop with the Sudetenland. Even though the document does ultimately make its way to Chamberlain himself (played by the always-brilliant Jeremy Irons), history does not change; Chamberlain is so bent on preserving peace and preventing the war right in front of him that he is incapable of considering any alternate course of action.

On the whole, Munich: Edge of War is a sumptuous period piece, and we very much enjoyed its visual portrayal of the late interwar years, from sets to material culture. Even in a story about strictly political history, it makes sure to include the racist persecutions that undergirded Hitler’s regime (more on that later), and it was gratifying to see what we can only assume is a somewhat accurate portrayal of how frantic and all-consuming being even a relatively minor public servant can be (though Bryan was repeatedly annoyed by the inability of Legat’s wife to comprehend the same). While Legat is a creation for the story, the character of von Hartmann was based off real anti-Nazi German diplomat Adam von Trott zu Solz, who was involved in a number of efforts to depose Hitler and was ultimately executed for his role in Project Valkyrie.

Problems arise, however, in Munich’s use of its maguffin, the document detailing Hitler’s plans for Europe. This document was indeed real, and the movie provides the accurate date of November 5, 1937 for the meeting that produced it. However, it only came into the Allies’ possession after the war was over. The decision to move its capture up to before the outbreak of war essentially serves, then, to introduce hindsight into the narrative, ahistorically confronting Chamberlain with the likely consequences of appeasement in real time. That he continues down his chosen path emphasizes both his commitment to peace (and deathly fear of being responsible for another apocalyptic war) and moral failure to confront despotism when it is revealed to him.

Chamberlain is not the only morally questionable character in the film, either. Through flashbacks, viewers learn that only five years previously, von Hartmann was in fact a staunch supporter of Hitler, believing him to be Germany’s best chance of renewal (his historical inspiration was always an opponent of the Nazis). By the time of its titular conference, Munich has introduced two mysteries: von Hartmann’s change of heart, and the disappearance of the third member of Legat and von Hartmann’s college circle, a German woman named Lina. We were fairly sure these two would be connected, and right we were; it is revealed that von Hartmann abandoned the Nazis when Mina was arrested for protesting, discovered to be Jewish, and brutally attacked while in prison, resulting in her hospitalization in a vegetative state. While we certainly appreciated this inclusion of the oppression that would lead to the Holocaust in a movie whose storyline did not strictly require it, we couldn’t help but feel that it cheapened the character of von Hartmann, who could only admit Hitler’s evil once it personally affected him and the people he cared for.

These objections thankfully don’t sink the film entirely, simply lessening the impact of the questions it tries to ask, and we still thoroughly recommend it to any interested in this period of history. While maybe not to the level it intends, Munich certainly challenges modern perceptions of Chamberlain and his foolhardiness in ways that Bryan anticipated back in that Modern British History discussion, and we could easily see it being assigned in high school or college classrooms as the inciting assignment for a classwide discussion of its attempts to complicate our modern narrative of the Second World War.