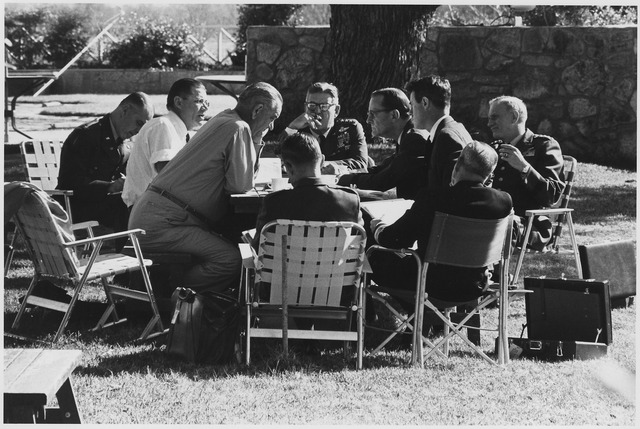

Last summer, I started a series on whether the U.S. could have won the Vietnam War. My initial post examined the political consequences of the U.S. decision to back a coup against South Vietnam’s President Ngo Dinh Diem and how Diem’s assassination disrupted any real chance to create a viable, stable South Vietnamese state. Today, I continue that series examining Lyndon B. Johnson’s fateful decisions about the Vietnam War in the year after JFK’s assassination.

Lyndon B. Johnson had big plans for his presidency. He would invoke his assassinated predecessor’s hopes to secure legislative action on civil rights, he’d lay the groundwork for his Great Society programs to eliminate poverty, and he’d prove to all his naysayers and critics that he was not a softie on Communism on the world stage by pummeling North Vietnamese Communist forces into negotiations to end the civil war and guerrilla insurgency that threatened the U.S.’s beleaguered South Vietnamese ally. Johnson succeeded in passing critical legislation to both combat racial discrimination and poverty, but his plan to force the North Vietnamese into negotiation through the use of arms did not bear fruit. That failure was largely due to his own miscalculations as Commander-in-Chief–miscalculations that made it unlikely the U.S. could ever achieve victory (a stable, robust, non-Communist South Vietnamese state) in the Vietnam War.

Johnson’s administration faced an escalating crisis in South Vietnam. The South Vietnamese government was unstable, corrupt, and unable to manage its military affairs; the ARVN itself hemorrhaged recruits and South Vietnamese generals squabbled more with one another than with NLF or North Vietnamese forces. American military and civilian officials believed that the U.S. had to take action to save South Vietnam or suffer a blow to American credibility on the world stage. The time for more decisive intervention apparently had come.

However, despite the warnings from some key naysayers in the U.S. government,, the Johnson Administration sought to use military power to achieve political results. It also planned to fight a conventional war against the combined irregular and regular forces of the North Vietnamese. It would bomb the North Vietnamese into negotiations and shore up South Vietnam long enough for its governing institutions to reform. That was the plan, at least. Yet Johnson and the Pentagon did not map out a clear path to achieve those results. Moreover, Johnson feared that escalating a war in Vietnam would imperil his reelection chances in 1964 and his plans for sweeping domestic reforms in Congress. To cut it both ways, Johnson chose the middle course the Pentagon offered: some bombing initiatives against the Ho Chi Minh Trails in Laos, a limited bombing campaign in North Vietnam, and the deployment of Marines to protect U.S. bases in South Vietnam. Faced with the magnitude of North Vietnamese incursions and attacks, however, this moderate plan ballooned into the sustained bombing campaign known as Operation Rolling Thunder and authorization for U.S. troops to take offensive actions against the NLF and North Vietnamese military.

Things had escalated; the U.S. had committed itself to fighting a ground war in Vietnam. It did so without consulting the South Vietnamese government and with little domestic debate. LBJ wanted it that way. He told Congress that U.S. military moves in Vietnam were in response to North Vietnamese aggression, sold the war as an essential fight for American security, and built a broad but thin layer of public support for the initiative. Even as his advisors urged him to ask Congress to increase taxes and authorize Johnson to deploy the National Guard and Reserves, Johnson refused. He feared the domestic implications of an extended debate on a war he felt the public little understood. He also thought that calling on U.S. Reserves and the National Guard, the next tier of trained and combat ready American soldiers, risked inviting Chinese and Soviet intervention in Vietnam, too. Better to have the military draft the soldiers it needed than alarm the public that the nation was on a war footing, so Johnson thought.

Johnson’s decisions laid the groundwork for future problems. First, he initiated a massive war in Southeast Asia without a debate in Congress or with the American public. Second, he committed America’s youth, especially working-class teenagers, to fighting and dying in this war without the strategic and tactical plan to win against the dual irregular and conventional military forces arrayed against South Vietnam. Third, he did not articulate a clear goal other than shoring up the South Vietnamese and determined that a limited bombing campaign could scare the North Vietnamese enough that they’d negotiate. With little public awareness or debate to ensure support for this effort, without a clear plan for how to win, and with hope only in a quick military victory, Johnson led the U.S. into war without a plan. That, even without the benefits of hindsight, is not a recipe for military or political success.