On the heels of the controversial Dobbs decision in June of 2022, 2023 saw the United States Supreme Court enter the news like never before–and not in a flattering way. As accusations of ethical violations swirl amid conservative justices’ entreaties that people need to stop disrespecting the Court’s unimpeachable reputation. Yet just how unimpeachable have the Supreme Court’s decisions been throughout the years? When one looks closely, numerous cases emerge in which justices’ decisions are not simply disagreeable or adhere to a repugnant theory of jurisprudence, but violate basic rules of legal process, logic, and even language itself. Taken together, an examination of all these cases argues persuasively that, far from being the impartial arbiter that it likes to portray itself as, the Supreme Court has always been a political institution just as flawed and susceptible to agenda-driven manipulation as any other human political institution. In this first installment of a new series, Bryan examines the most famous of these decisions, one that contributed significantly to the outbreak of the American Civil War.

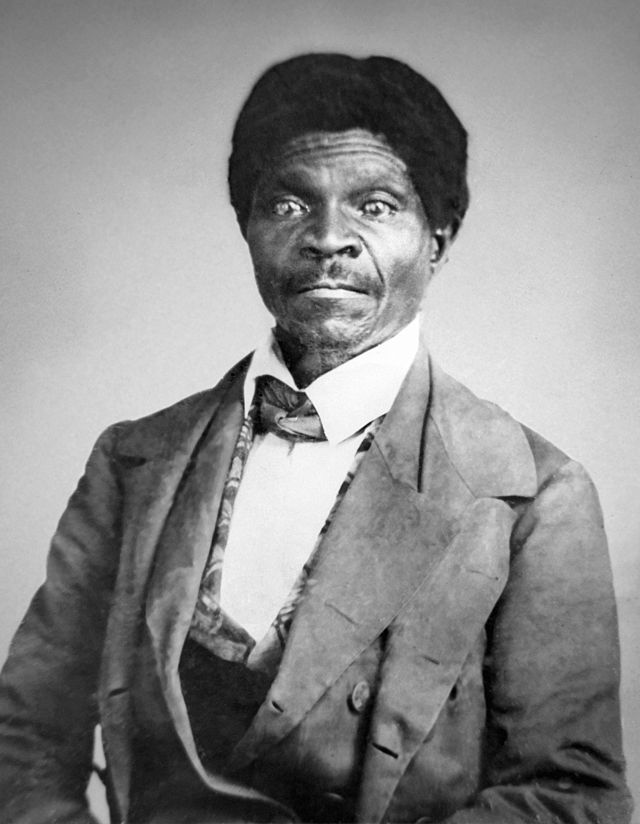

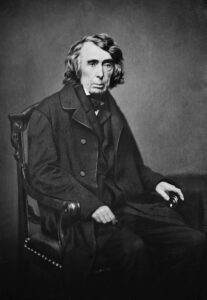

There are certain terms from our education that we hear so many times, across so many years of instruction, that they become part of the palimpsest of our thoughts, instantly recognizable for even those who never pursued that subject beyond their middle or high school classrooms. One such historical mainstay is the infamous Dred Scott decision, delivered by the United States Supreme Court in 1857 on the eve of the American Civil War. Widely heralded (by both sides of the modern political aisle, interestingly enough) as one of, if not the, worst Supreme Court decisions in history, the 7-2 verdict of the pro-slavery majority was a key factor in stoking the fires of sectional conflict that exploded into outright war four years later. No one denies that the court’s decision, written by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, was racist in the extreme, but in reading James McPherson’s landmark Battle Cry of Freedom last year, I was reminded just how offensively atrocious this landmark of American legal history was.

Those who remember Dred Scott v. Sandford from their history classes may recall the general overview of the case: that Dred Scott, a slave, sued for his freedom because his master had taken him into a free state, and that the Supreme Court had rejected his case on the grounds that he had no right to bring suit due to his status as a slave. All true, at least in generalities, but the details of the case go far deeper. Scott had lived with his master, US Army surgeon John Emmerson, for two years in Illinois (a free state) followed by two years in Fort Snelling, an army post what was then the Wisconsin Territory, part of the Louisiana Purchase above the latitude 36° 30’ and thus free territory according to the Missouri Compromise. When Scott ultimately sued for his (and his wife’s) freedom from Emmerson’s wife after Emmerson had died, three questions were thus brought before the judiciary. As a slave, could Scott bring suit in Federal court? Did living in a free state make him free? And did the Missouri Compromise, a Federal law administering territory, truly have the power to ban slavery?

As one might predict, such loaded questions bounced back and forth through the courts, decided, reversed, and reconfirmed, for nearly eleven years before finally, it could be kicked no higher and rested before the Supreme Court for judgment. At the time, a majority of justices were Southern or pro-slavery, and so few expected a decision in Scott’s favor. The Missouri Supreme Court and federal circuit court had decided that, though Scott was a citizen and could therefore bring suit, his home state of Missouri’s law still applied to him and his master regardless of where they temporarily lived, and thus he was not free (an admittedly odd extraterritorial interpretation that calls into question just what the nature of state laws are). If they had wanted to simply maintain the status quo and not make waves, the Supreme Court could have simply upheld this decision–which they very nearly did. Yet when it became clear that the two anti-slavery justices of the Court intended to write a dissenting opinion, Taney used the opportunity to fire a salvo of pro-slavery legislation from the bench that boggles the mind in its sophistry and bad faith.

To the case’s first question of Scott’s right to sue, Taney overturned all previous courts’ decisions by declaring that not only slaves, but all black people could never be considered citizens of the United States and have “any rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Taney further denied that the country’s founders included non-white people in their language of equality (somewhat fair, to be honest), but in doing so ignored the civil standing of freed blacks in many Northern states from the very beginning. And in perhaps the most laughable element of his opinion, Taney also wrote that just because some states granted black people citizenship did not mean they held Federal citizenship, as even other states did not have to respect those states’ laws–no matter that the Constitution itself says exactly the opposite in Section IV, Article 2: “The citizens of each state shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states.”

While some may think that this decided the entirety of the case, rendering the rest of Taney’s decision obiter dictum, or without the force of law–indeed that is how the case is often taught in high school classrooms–the fact that all three of these questions were before the court in their own right as part of the case meant that Taney was simply answering the question, not rejecting the case, and thus the other two questions remained to be answered. Now reverting back to the absolute sacrality of the Founders’ words, he maintained that, as slaves were considered property, to which all men have an inalienable right, no law that stripped property could be considered Constitutional. In a stroke, Taney had invalidated the very notion of a state banning slavery, yet he did not stop there. Rather than feel that this was sufficient to answer both remaining questions, he also felt compelled to state that Congress did not have the power to pass laws regarding slavery in the territories. Yes, the Constitution may say that Congress had the power to make all “needful rules and regulations” for the territories, but according to Taney’s bizarre interpretation, rules and regulations were not laws.

It is little wonder that the Dred Scott decision provoked such an outcry among Northerners when it was announced, further hardening their hearts towards any attempt at compromise with their Southern neighbors. At the beginning of the decade, Congress had declared through the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 that all citizens were required to help recapture runaway slaves if asked, and now the Supreme Court had discarded precedent, history, and the explicit wording of the Constitution itself to declare that slavery could never even be legislated against in their own states. Thankfully the force of this decision, whether obiter dictum or not, was negated by the passing of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments outlawing slavery and establishing birth citizenship, but it remains a low point in the history of the Court and one of the earliest instances of justices making a mockery of their position in order to advance their own politics.

To be continued…