by Bryan & Heather

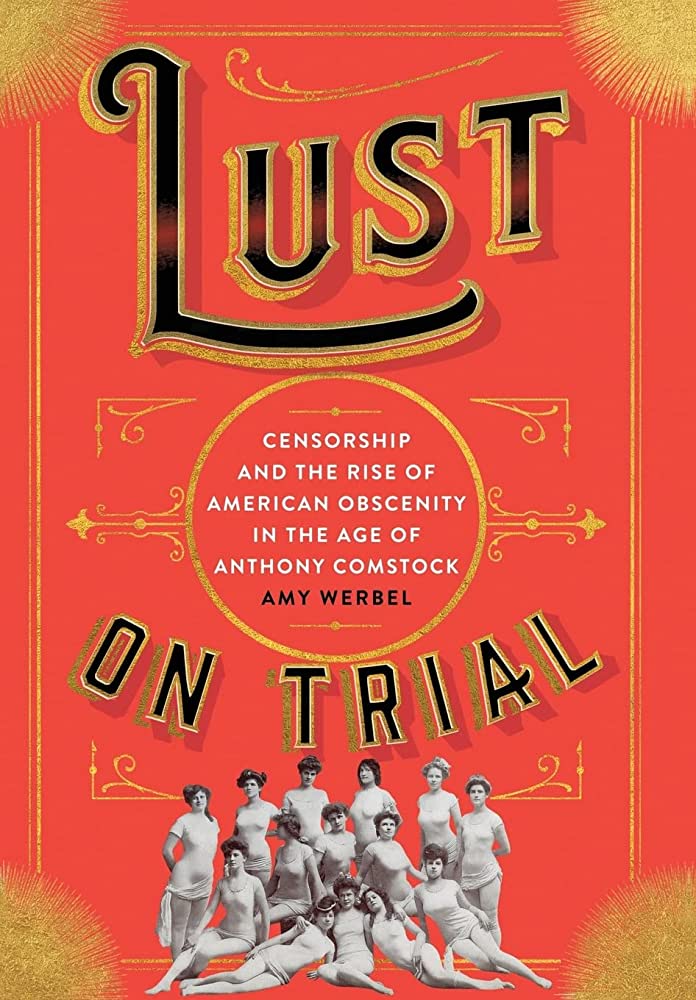

Werbel, Amy. Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock. New York: Columbia University Press, 2018.

One can only watch so many period pieces set in Gilded Age New York before inevitably coming across the name Anthony Comstock. We had a passing familiarity with this legend of American Puritanism from our previous studies of the period, but first encountered him in his own right in Sex and the Civil War, where Judith Giesberg devoted an entire chapter to Comstock’s experience (unsuccessfully) policing morality among Union soldiers as a young man. For the height of his career, however, we would turn to another book waiting on our shelf: Amy Werbel’s study of obscenity, censorship, and the triumph of free speech, Lust on Trial.

While its title suggests a more period-focused study framed by Comstock, it quickly becomes clear that Lust on Trial is more biography than monograph, and seemingly for good reason: the development of legal standards for obscenity and their prosecution by private organizations in the late nineteenth century is so bound up with the efforts of Anthony Comstock that it would be hard to separate the two. Yet as always, context is key, and Werbel conducts her readers through Comstock’s early life in Puritan Connecticut to his time as a young man in New York City, clearly establishing the environment that formed such an uncompromising and inquisitorial point of view towards any expression of sexuality. His subsequent career as chief agent for the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice is as entertaining as it is concerning for a modern audience as a private organization lobbies for laws that severely restrict free speech and prosecute that law themselves, all while receiving increasingly inventive and effective resistance from proponents of free love and free expression. Comstock’s unchanging views of morality over nearly half a century ultimately as much his downfall as his overreach when he leads the NYSSV into a unwinnable crusade against the high art enjoyed by New York’s Gilded Age elite. It’s often remarked how we must remember how the worldviews of historical figures was very different from our own, yet in the ultimate failure of Comstock’s censorship Werbel deftly illustrates that sometimes, historical figures had remarkably modern opinions, too.

Though Lust on Trial ends on an upbeat note concerning the birth of modern free speech and the inherent weakness of censorship as practiced by the NYSSV, we couldn’t help but derive a radically different message. We would guess that Werbel’s manuscript was finished before the election of Donald Trump in 2016 and the accompanying global rise in far right movements, and for us, observations regarding the origins of the peculiarities and conservatism of much of American public morality (such as what is and is not appropriate to be shown on network television, for example, or the focus on guarding young men’s virtue rather than addressing their internalized misogyny) would have been much more pertinent; her remark that Planned Parenthood’s future seems assured rang especially hollow for us, even for the early 2010s. Werbel’s focus on Comstock himself also seems to have blinded her to pursuing other, more historically interesting avenues like how such persecution interacted with racial, sexual, and gender identity–all subjects mentioned in passing, but never truly in their own right.

Despite these drawbacks, Lust on Trial remains one of the best books we’ve read on the foundations of American morality, censorship, and the evolution of our interpretation of the most fundamental rights guaranteed in the Constitution. Readers may need to draw some of these connections on their own, but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing; active engagement with such ideas, especially in a world significantly less rosy than the one found Werbel’s introduction, is the best one can ask of such relevant works of history.