The amount of time (or lack thereof) to cover history curricula in modern high schools has become almost proverbial among students and teachers alike. Francis often shares with me that “Lincoln has to be dead by December,” and my own students often become stressed when faced with barely more than a month to cover the entirety of the Cold War—precisely the era they are least familiar with. I often reflect on how much more difficult it must be for them; I faced much the same difficulties when I was in high school a decade ago (in the most egregious case, my AP European History class did not even reach the First World War by the end of the year, leaving us to study the entire 20th century on our own for the AP test), and now they have another ten years of history to cram into the same amount of school. As I reflected on students’ plight this past spring, a burning question slowly dawned on me: exactly how much history have we been cramming into the school year, and how long have we been doing this?

I began, as any good historian does, at the beginning. Education has existed in the United States in some form since before its founding as a nation. Before the nineteenth century, though, any schooling children received was haphazard and depended on region. In the northeast, education was fairly widespread, with some school even publicly funded, whereas schools in the south and west were almost invariably sparse and funded by private donations.

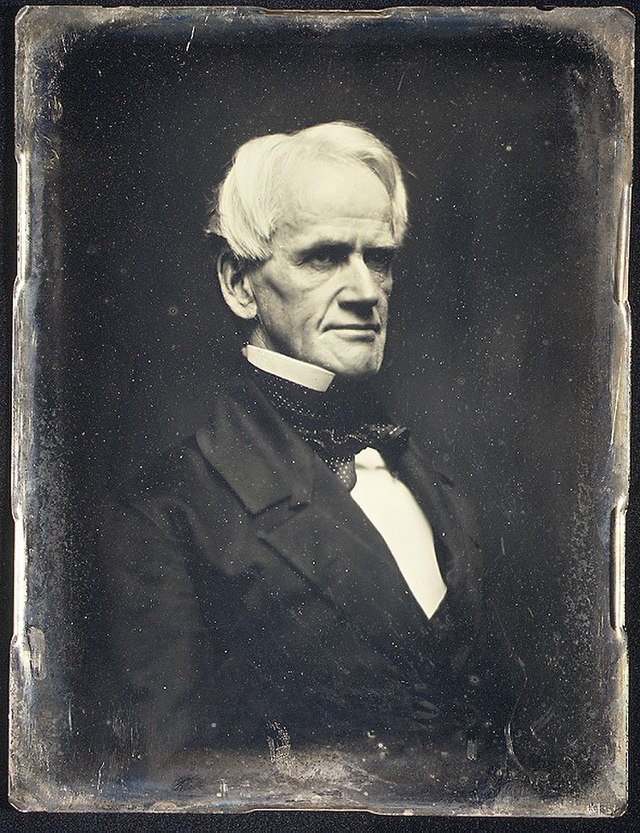

In 1830, however, the world of education changed with Horace Mann and the experiments of the state of Massachusetts. Mann advocated for mandatory public schooling of all children, and Massachusetts soon after established free school, the first public high school, and its own Board of Education. The remainder of the century would see the campaign for free, mandatory, public school take off, with the Federal Department of Education established in 1867 and 78% of primary school-aged children enrolled by 1870, but secondary education would take still longer. Only in the first decades of the twentieth century, as new labor laws drew children out of factories and into the classroom, did high school gain traction, yet still only 55% of eligible students were enrolled by 1970 (only in 2014 would that number reach 90%).

The decentralized nature of education in the United States, however, means that even once it had arrived in its (mostly) modern forms, mandatory public education remained highly varied by region. The most important early difference lay in the length of the school year. Schools’ quality was initially judged by how many days they were open for instruction; thus, urban schools usually operated year-round, while some rural schools operated for barely more than 6 months due to the demands of an agrarian economy. Only in the middle of the twentieth century would these two approaches stabilize into the modern school year: approximately 180 days, with a 2-3 month summer break.

And this, by and large, is where secondary school has remained for the past three quarters of a century or more; in fact, the length of the school year, and thus the amount of instruction available, has remained remarkably standardized across time and space. My students in California attend school for approximately 180 days a year, approximately 7 hour days. So did I, a decade ago, in both Pennsylvania and Connecticut. So did my mom, in suburban Reading, PA, in the mid 70s, as well as my dad, in rural northeast PA in the late 60s—both, amazingly, with class periods almost exactly as long as mine (they both think I had way more homework than they did, and I thought perhaps I had discovered a possible source of the modern homework overload, but other research and discussions with teachers indicate that teachers are generally assigning less homework, and that overload is usually either a result of weaknesses in foundational skills or cramming in advanced classes that were never meant to be taken all together).

What this means, then, is that the shape of American education, both primary and secondary, has hardly changed in close to a century, even while close to a century of human knowledge has been added to our world. Worries over flagging performance among American students compared to the rest of the world have been around since the 80s, yet these concerns have resulted in, at most, waves of standardized testing targeted at improving basic skills like reading (which, ironically, can only really be improved at home with conscientious parenting); I have never heard of any proposal to reform how we approach the school year, with one notable exception (more on that below).

Of course, due to American education’s regionalization (beginning to notice a theme? Stay tuned for a future post), I cannot speak with confidence about what any curricula do or do not do to rectify this problem. I can, however, comment on my own experiences, including the Advanced Placement system, one of the only curricula that is standardized across the nation. What I have to say is not good. Some subjects, like math or science, can see topics rendered outdated or redundant by new information, and thus can self-police their subject matter. Others, like English/Literature, have always been exercises in selection from a huge corpus, and so do not face a problem of instructional time as much as a problem of who, exactly, is curating the reading list and leaving out more modern, more diverse works.

The state of history classes, however, has grown increasingly worse and, dare I say, dangerously negligent over the past 50 years. Unlike those other disciplines, history is very hard to self-curate; an event does not lose its significance the older it is, and usually precisely the opposite is the case. My mom was part of the first generation of AP students in the 70s; fifty years later, after nine presidents, 4 major conflicts, 3 social revolutions, 2 political revolutions, and countless domestic scandals and tragedies, my students are afforded no additional time to make up the gap. Predictably, as mentioned above, it is precisely the more modern history that draws the short end of the straw in this arrangement. This isn’t just concerning from a purely academic sense; if history is to have any utility in the present, it is to understand how we got here and how we might proceed. I might even argue that, if high schoolers nationwide had received a competent education in the history of the past 50 years, our current political polarization would not be as stark.

So what is to be done about this issue? The most obvious answer, and one that has the highest likelihood of gaining traction in the short term, is reforming curricula to cover more, more competently, within the current educational framework. Redraw history courses into more general thematic treatments that jettison a lot of specific, less relevant details; split the AP and/or all American history into 2 years, divided roughly around the turn of the 20th century; transform government classes into learning American government through learning the history of the last half century; many options present themselves. My most pressing worries, stemming from my own professional specialization, are for history; other subjects may arguably be more important to add wholesale to high school and even primary school curricula. Things like internet literacy, personal finance, even health class need to be updated and made real, required, classes instead of the electives or jokes they are today.

At some point, however, no matter how efficiently we teach, we will run out of room in students’ schedules and school years. One proposal to address this obstacle that has been kicking around for years, and to which I alluded above, is returning to year-round school. I don’t know if this could ever become a reality, for two reasons: Americans love their summer vacations (which have now become an integrated part of our society, culture, and economy), and many of these plans do not include commensurate pay raises for teachers to reflect their loss of personal time. Even this would only go so far, and the alternative, or ultimate recourse, is to add on years of schooling. This of course would come with its own deep-seated societal resistance and financial problems (though it might ease those of students), and I honestly do not know which way Americans would rather go.

One thing I do know, however, is that no edifice can be useful if it is not reformed for a century; it is high time we reconsider radically reshaping what school looks like in the United States.

Sources & Further Reading

DiNuzzo, Emily. “This is what going to school was like during the decade you were born.” Insider, August 1, 2017. https://www.insider.com/what-going-to-school-was-like-throughout-history-2017-7.

Kober, Nancy & Diane Stark Rentner. History and Evolution of Public Education in the US. Washington, DC: The George Washington University Center on Education Policy, 2020. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED606970.pdf.

Pedersen, James. “The History of School and Summer Vacation.” Journal of Inquiry & Action in Education 5, No. 1 (2012): 54-62. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1134242.pdf.