In a long-overdue second installment of our series that began with “‘Fair Deceivers’: Victorian Women in Male Attire,” today we’ll continue to explore the phenomenon of American Victorian women who chose to don men’s fashion. Diving into my research on the topic, I was surprised just how many instances of the practice were documented in newspapers of the era. Previously restricted to actresses on the stage (and even then, looked askance at), in Victorian America, female crossdressing spilled over the stage and into public life. The women who made the choice to wear men’s clothing in this era of rigid gender norms did so for a wide range of reasons that we’ll analyze over the course of this series. Today’s focus will be lighthearted: female crossdressing within the paradigm of humor, fun, and adventure.

In some ways, American humor reached maturity in the Victorian era. Mark Twain rose to fame, cheap paperback novels spread like wildfire, and American newspapers pared down the historically erudite and wordy political cartoon and sprinkled alongside them a regular helping of jokes and cheeky poems. Some revolved around the very topic of women in men’s attire. On the eve of Victoria’s reign, Raleigh’s North-Carolina Standard on March 10, 1836 published this punny poem titled “Singular Security”:

“What pity ‘tis,” said John the sage,

“That women should, for hire,

Expose themselves upon the stage,

By wearing men’s attire.”

“Expose,” cries Ned, who loves to jeer;

“In sense you surely fail:

What can the darlings have to fear,

When clad in coat of male!”

As the century progressed, humorous snippets around female crossdressing stepped outside the world of the theater and began to demonstrate the increasing frequency with which the occurrence made the papers. While nonchalantly mentioning female crossdressing, a joke from Nebraska’s Lincoln County Tribune on July 14, 1888 also incorporated a jab at President Grover Cleveland: “An Iowa woman masqueraded as a man for five years and was never suspected, although she associated with men. Still the record, strange as it is, has been beaten. Now, there’s Grover Cleveland. He has masqueraded as a statesman for about five years and yet his party lias never even suspected his deception.” Still other jokes poked fun at gender norms of the time, as when the Laporte, PA, Sullivan Republican asked, “How did you discover she was a woman masquerading as a man?” and the response was “She sent me a letter with two postscripts.” (In my opinion, this joke is remarkably timeless in its stereotyping.) Evidently, women dressing as men was not always understood to be as nefarious or wicked as one might expect given the Victorians’ reputation for straight-lacedness.

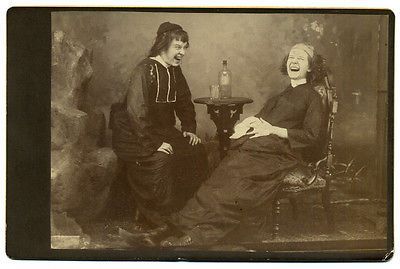

In practice, too, you could find women playfully bending gender expectations. As I conducted my research, I came upon multiple accounts of cavorting and tomfoolery that ended in gender-bending fashion experiments. Some were classic examples of “kids being kids,” like when two Dubuque teens “put on male attire the other evening and promenaded up and down the street for about an hour,” as reported in the Omaha Daily Bee on May 16, 1884. Adults often blamed their choices on having “imbibed a little too freely,” as when a pair of newlyweds decided to dress the bride in her groom’s suit and stroll around town. According to the St. Paul Daily Globe on January 23, 1889, a police officer “promptly called the bluff” and they were jailed overnight and fined the following morning before release. Interestingly, both the husband and wife were fined, “Lincoln $7.50 and his wife $12.20,” the perhaps unspoken message being that it is a husband’s duty to see that his wife conduct herself properly in society. An inebriated young San Francisco woman partying on Independence Day in 1906 was similarly goaded by her friends into putting on men’s clothes before walking downtown. Thankfully for the young woman, her arrest did not end in jail time as it did for the newlyweds in St. Paul, though the judge gave her a stern scolding: “I would strongly advise you never to put on male attire again. Such practices are both dangerous and decidedly improper. I think you have already been punished thoroughly. You have had your picture in the paper and all that sort of thing. I don’t believe your action was malicious, but more in a spirit of mischief. Under the circumstances I will not send you to jail.” No doubt the young woman was relieved.

Perhaps most interesting to me among these tales of Victorian women who cross dressed purely for a laugh is that of a “well known and respectable South Side lady” reported in West Virginia’s Wheeling Register on March 14, 1892. Like the newlyweds, this woman went out accompanied by a man – this time a friend – “just for the fun of the thing.” After a group of young men “noticed her peculiar conduct and followed the pair,” the woman and her friend were stopped by a Lieutenant Gaus. In contrast to so many others with similar stories, however, this “well known and respectable South Side lady” was not arrested and was instead allowed to go on her way with only a lecture as punishment. We can’t be sure how the woman’s social class may have influenced the outcome of the interaction, but its prominent mention in the newspaper piece did give me pause. In one of the future posts in this series, we’ll focus in on social class and its role in Victorian women’s crossdressing in greater detail.

Stay tuned for more to come!