Art and art museums aren’t everyone’s cup of tea. A lot of folks consider them excruciatingly dull or painfully pretentious. From many of us, the best you’ll get in an art museum is a half-heartedly thoughtful “hmm” before we continue on to something more exciting. I personally do enjoy art museums, but that’s mostly because I like to point at the silly faces and bodies I find and tell Bryan they look like him. (I’m also amused by depictions of babies by Medieval and Renaissance painters who you’d assume had never seen a human baby.)

Art isn’t usually one of the media types we review on Concerning History, either, but when I recently visited the Birmingham Museum of Art for the second time, I found myself musing over just how many pieces on display were ripe for discussion here on our blog. So today, I’ve picked out three American pieces for your historical and artistic consideration.

The Barricade (1918) by George Bellows

The Barricade (1918) by George Bellows

Part of a larger series of five, this painting depicts an atrocity committed against World War I civilians. In the piece, invading German soldiers use Belgian civilians as a human barricade against enemy fire. Bellows portrays the civilians nude, posed in the style of martyred saints. In doing so, he evokes visual language familiar to those versed in art history. His allusion to atrocities centuries past prompts us to reconsider the bloody sacrifice of Belgian citizens in a religious framework, urging the viewer to recognize the momentous tragedy of their murders.

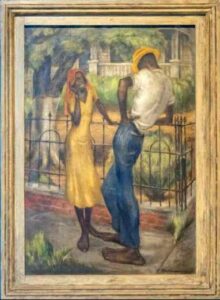

Conversation Piece (1936) by Charles Eugene Shannon

A native Alabamian, Charles Eugene Shannon stepped outside the accepted cultural bounds of his whiteness to depict many scenes of black life in the 1930s. This painting takes its name from an eighteenth-century genre that portrayed small groups chatting in domestic or landscape settings. In contrast to the well-heeled white norm of eighteenth-century conversation pieces, though, Shannon depicts a flirtatious Black couple clad in modest clothing and bare feet. His choice of subject is decidedly provocative for the year and region of his work, centering poor Black Alabamians in a scene of joy, not subservience.

Unfit Frame (2016) by Titus Kaphar

Unfit Frame (2016) by Titus Kaphar

This contemporary work by the same artist as Beyond the Myth of Benevolence critiques the very gallery in which it hangs. “The story of English art in the 1700s as told by the works in this gallery is lopsided,” it reads. “It masks an important aspect of British history by not referencing its colonies and its deep involvement in the human trafficking of enslaved people. In many instances, this created the wealth that allowed the people portrayed here to commission those works in the first place.” Kaphar plays with size, texture, and multiple media to build a visual argument: Art isn’t innocent, and neither is its curation.

So, there you have it. Three pieces at the Birmingham Museum of Art that scratched the historical itch. Next time you end up in an art museum, whether of your own volition or dragged by a loved one, keep an eye out for more examples of art in conversation with history. You might be surprised by just how many there are.