Only three days remain in 2021, and it’s time once again for our annual look back on how we think this past year will be remembered by historians to come. This year has certainly been filled with notable events, and in a slight twist from our usual format, we intend to not only talk about them but provide points of historic comparison to investigate how this year has paralleled (and departed from) the larger flow of history.

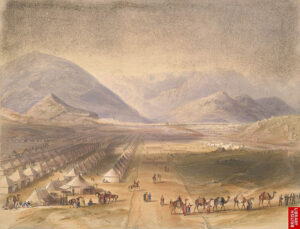

BC: A huge event of 2021 that lies close to my own specialization was the withdrawal of United States forces from Afghanistan. The end of this conflict marked the end of the United States’ longest war; beginning in 2001 in the immediate aftermath of the September 11 terror attacks, America’s presence in Afghanistan was nearly 20 years old by the time of the withdrawal this summer. For many, this fulfilled a prophecy made at the time of the initial invasion: Afghanistan is the graveyard of empires, and it was typical American hubris to think we’d be any different. This reputation, however, is less than two centuries old, and peculiarly European. Alexander the Great had no trouble conquering Central Asia, and his Helenistic successor states had no problems ruling there for centuries. Those kingdoms in turn gave way to Sassanid Persia and the Sogdian merchant city states, which in turn were conquered by the ascending Islamic Caliphate. Then, after the Mongols steamrolled through, Kabul itself was the seat of empire, with Timur and his Mughal successors both conquering vast Central Asian empires from it.

Ironically it is the golden age of European empire and technological divergence that forged Afghanistan into the bane of so many world powers. Britain fought three wars to control India’s northwestern frontier, only outright winning the third (in 1919). The Soviet Union famously got bogged down in their own invasion, and now the United States has fled with its tail between its legs. It can be depressing how similar these conflicts have been. Afghanistan has consistently proven easy to initially conquer, leading to a decrease or dispersal in effective fighting forces in the region. Then, European support for unpopular and obscenely corrupt governments leads to widespread resistance in the outlying provinces that Western powers seem incapable of reversing due to an inability to empathize with Afghans on their own level. I can only imagine that future textbooks will list this most recent failure in Afghanistan amongst all the many foreign policy blunders of the United States in the past 70 years as we increasingly make the world less safe for democracy through not knowing what we’re doing when we invade another sovereign nation.

FB: One of the most significant events of 2021 for me has to be the emergence and spread of new Covid-19 variants that perceptively bludgeoned the efforts of many governments to finally mitigate, contain, and overcome the SARS-Cov-2 virus. While adequately warned about the threat of variants and the ways in which mutations could make Covid-19 more deadly, more transmissible, or both, the politics of public health necessitated simple, straightforward messages to convince people to get vaccinated. In other words, get the vaccine and this will end. However, outbreaks are anything but simple. Now, faced with the Omicron variant, the worry and disruption that has upended (or sadly ended) many people’s lives strikes again. Two historical events prior to our current outbreak serve as solid precedents for these emerging variants and the virus’s durability. The first are the successive waves of Bubonic Plague that hit Eurasian societies from the 1300s until even the 1800s, often causing widespread panic and the spread of other types of plague too (pneumonic rather than bubonic, for example). These disruptions also inspired hosts of fake remedies to deal with plague or ward it off, just like the “junk science” that infests Americans’ newsfeeds tells millions to do everything but take lifesaving vaccines. In contrast, however, is a recent account I read of the successful containment of a typhus outbreak in the Warsaw Ghetto during World War II. I honestly marveled at the skill, tenacity, and pragmatism of the persecuted, malnourished, and despairing Jewish people who rallied behind the leadership of the ghetto’s residents who had had medical careers prior to the Nazi invasion of Poland. Together they beat back typhus and saved the lives of many. It’s honestly nothing less than heroic and inspirational that they did this and frankly damning of the ways Americans have failed throughout this entire pandemic to meet the moment.

FB: One of the most significant events of 2021 for me has to be the emergence and spread of new Covid-19 variants that perceptively bludgeoned the efforts of many governments to finally mitigate, contain, and overcome the SARS-Cov-2 virus. While adequately warned about the threat of variants and the ways in which mutations could make Covid-19 more deadly, more transmissible, or both, the politics of public health necessitated simple, straightforward messages to convince people to get vaccinated. In other words, get the vaccine and this will end. However, outbreaks are anything but simple. Now, faced with the Omicron variant, the worry and disruption that has upended (or sadly ended) many people’s lives strikes again. Two historical events prior to our current outbreak serve as solid precedents for these emerging variants and the virus’s durability. The first are the successive waves of Bubonic Plague that hit Eurasian societies from the 1300s until even the 1800s, often causing widespread panic and the spread of other types of plague too (pneumonic rather than bubonic, for example). These disruptions also inspired hosts of fake remedies to deal with plague or ward it off, just like the “junk science” that infests Americans’ newsfeeds tells millions to do everything but take lifesaving vaccines. In contrast, however, is a recent account I read of the successful containment of a typhus outbreak in the Warsaw Ghetto during World War II. I honestly marveled at the skill, tenacity, and pragmatism of the persecuted, malnourished, and despairing Jewish people who rallied behind the leadership of the ghetto’s residents who had had medical careers prior to the Nazi invasion of Poland. Together they beat back typhus and saved the lives of many. It’s honestly nothing less than heroic and inspirational that they did this and frankly damning of the ways Americans have failed throughout this entire pandemic to meet the moment.

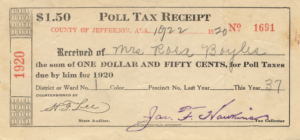

JL: Despite serving as a bookend of the openly authoritarian Trump administration, 2021 also saw a dramatic acceleration in the efforts to undermine democratic processes and principles across the United States. In the wake of President Joe Biden’s victories in new swing states like Georgia and Arizona, Republican-led state governments in these states and others sought to impose new barriers to voting access and even make it easier for these same state governments to overturn the will of their own voters by appointing their own slates of electors for presidential elections. At the same time, 2021 followed a census year and therefore saw many states approve new congressional maps or draft maps to be approved early in the new year. Gerrymandering within these maps will both make it more difficult for what otherwise might be wave elections to flip or even threaten the balance of power in Congress and ensure that many members of the House fear primary challenges more than general election contests as the greatest threat to their reelection. All of these trends may combine to make 2021 the worst year for democratic backsliding in the United States in a century and a half.

Democratic backsliding is nothing new in the United States. The events of 2021 are only the latest in a longer trend of dramatic polarization that began in earnest in the 1990s, most notably with House Speaker Newt Gingrich and the birth of Fox News. Prior to the current moment, the end of Reconstruction stands out as the best example of democratic backsliding, though the means differed dramatically. Voting rights laws in the wake of Reconstruction were often more explicitly racist and enforced by state-sanctioned personalized violence, neither of which have by and large defined the present moment (so far). Nor were the largest divisions in the post-Reconstruction era partisan. For the century following Reconstruction, party politics relied on building broad coalitions that could compete across geographically diverse areas, even if it made ideological purity and cogency challenging at times. The ideological sorting of the two major political parties in the last forty years has upended the post-Reconstruction authoritarian playbook, making partisan control the ultimate goal.

KL: Lest we leave the impression that nothing potentially positive came out of the year, I think it’s worth pointing to the significant revival of labor power and union support. During the early months of the pandemic, America celebrated its essential workers in a way that left some people scratching their heads as to why it was so hard for our “heroes” to make ends meet.

KL: Lest we leave the impression that nothing potentially positive came out of the year, I think it’s worth pointing to the significant revival of labor power and union support. During the early months of the pandemic, America celebrated its essential workers in a way that left some people scratching their heads as to why it was so hard for our “heroes” to make ends meet.

Since then, we’ve seen a resurgence in worker activism, as they cash in on their public support and the leverage of a job-seeker’s market. Despite a setback in Bessemer, unions are pushing ahead at Amazon, Starbucks, and elsewhere. At my alma mater, Columbia University graduate student workers continue their years-long negotiation for a fair contract. Even in the absence of unions (or at least the distant threat of them), the Great Resignation has put employers on notice that essential jobs can’t be minimum wage anymore. And with extended unemployment benefits wrapping up, it’s becoming apparent that there’s something bigger at work than Americans staying home.

Among those who feel nostalgic for the heyday of unions, it’s sometimes possible to look back in retrospect and think of them as an inevitable result of industrial era capitalism–a very Marxist way of thinking about it–rather than the result of a hard-fought struggle with frequent losses and crushing setbacks. In fact, it took decades of organizing, the ideological threat of an alternate economic system, and a global financial crisis to fully legitimize them and secure their seat at the table in the form of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935.

If 2021 had a theme, it’s that people are fed up. And in the same way that can be a bad thing for public health and democracy, it may also be the pathway towards a new normal in the workforce, rather than a return to the warped labor market of 2019. Or it could be a blip–this history stuff is weird like that sometimes.

HC: Exacerbated by COVID-19–related understaffing and factory closures, 2021 witnessed the spread of a new pandemic: mass supply chain disruptions. Across the United States and around the world, consumers experienced product shortages and delays for everything from furniture and appliances to foods and toiletries. A key contributor to the disruptions has been the surprisingly archaic tangle of marine cargo shipping. Inarguably the most farcical demonstration of this outmoded system came on March 23 when the Ever Given collided with the bank of the Suez Canal, where it remained grounded for six days and seven hours. (Talk about a Suez Crisis.) As the world watched on in horror, an estimated $60 billion of global trade hung in the balance. Some captains were so desperate that they resorted to rerouting their vessels around the Cape of Good Hope. Very eighteenth century of them.

But the maritime cargo shipping system was already broken before the Ever Given ever ran aground. Massive backlogs off the overwhelmed ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach have plagued the supply chain off and on for months; these ports alone admit approximately 40% of sea freight entering the United States. That’s a lot of burden to take on, even before a pandemic is thrown into the mix. From increased consumer demand to COVID-19 outbreaks at factories and ports, it’s been a tough year for the shipping industry. As the world economy seeks to adapt to these new rougher waters in 2022, perhaps it’s time to reevaluate this weathered system and maybe even look to the past for some new ideas.

2021 has certainly not been a year for the faint of heart, but we can hope that these and many other noteworthy events will find their proper future solution and place in history as we enter the second year of this new decade. Whatever the case, we here at Concerning History will be on hand to continue to observe, analyze, and contextualize what we see all around us. Best of luck to all in 2022!