Spring 2019 saw yet another HBO phenomenon in the form of the docudrama miniseries Chernobyl (reviewed here on Concerning History). The recent Emmys briefly brought Chernobyl back into the spotlight, and I heard again a complain I’d first encountered back when the show originally aired: there were no accents or, rather, there were the wrong accents. No character in the show speaks with a Russian or Ukrainian accent, and indeed most of the actors stick to their native British cadence. This sorely bothered some people, to the point of even not being able to finish the show. Heather and I, however, were not bothered by it in the slightest. It’s a rare moment when internet podcasters are on the side of historical accuracy and I am not, so why this seemingly uncharacteristic shift in perspective?

Spring 2019 saw yet another HBO phenomenon in the form of the docudrama miniseries Chernobyl (reviewed here on Concerning History). The recent Emmys briefly brought Chernobyl back into the spotlight, and I heard again a complain I’d first encountered back when the show originally aired: there were no accents or, rather, there were the wrong accents. No character in the show speaks with a Russian or Ukrainian accent, and indeed most of the actors stick to their native British cadence. This sorely bothered some people, to the point of even not being able to finish the show. Heather and I, however, were not bothered by it in the slightest. It’s a rare moment when internet podcasters are on the side of historical accuracy and I am not, so why this seemingly uncharacteristic shift in perspective?

As it turns out, language is possibly the only thing in historical media that gets a complete bye from me when it comes to assessing accuracy. A large part of this comes from my own viewing preferences. I prefer to watch my movies and shows, not read them, and so I appreciate it if a show set entirely in, say, feudal Japan, meant for an American audience, just has its characters speak entirely in English.

I also know that the demand for linguistic accuracy only goes so far in Hollywood. One genre in particular, and one that is near and dear to my heart, never makes any effort to achieve accurate accents: movies set in the ancient world. From the cheesiest of sword-and-sandal movies to prestige projects like Rome or Gladiator, these movies and shows are always filled with actors sporting cultured British accents, so much so that I’ve been pulled out of a movie when confronted with Romans speaking in plain American English! Indeed, there’s probably something to be said about our expectation that members of the premier ancient Western Empire be played by those who possessed the premier modern Western Empire, but that’s an entire other article.

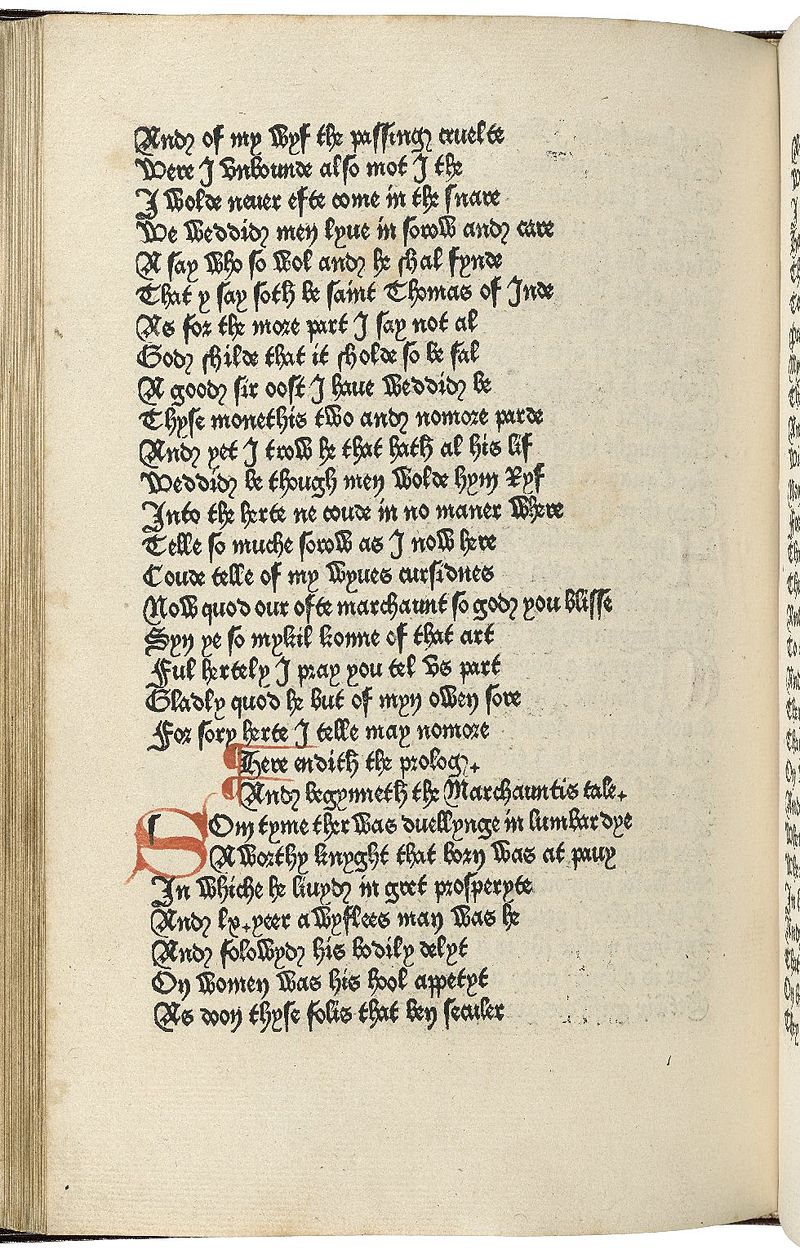

This particular case strikes the deeper historical reasoning for my ambivalence towards accents in historical media: the knowledge that we will never be able to achieve complete historical accuracy in anything we do, be it a doctoral dissertation or the most recent Oscar-bait period piece. It is nearly the first lesson in any Historical Methods seminar: while there may be such a thing as a complete, perfect picture of everything that went on in the past, we will never reach it, as that picture is filtered to us through incomplete records and biased, not-completely-trustworthy sources. This is why you’ll never find the word ‘truth’ in any of my historical writings, here or elsewhere; it’s too absolute a term for so incomplete an undertaking. This is especially the case when it comes to spoken language. We don’t know what Classical Latin sounded like, not really. All we have are educated guesses based on etymology, patterns of writing, and other such detailed hypotheses. Many like to joke about Kevin Costner’s lack of a British accent in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, but in reality no one would have been speaking with what we perceive of as a British accent in the thirteenth century; they would have been speaking the Middle English of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and the British accent as we conceive of it probably didn’t develop until the eighteenth century. We will never watch a film set before the modern era that actually captures what its characters would have sounded like, so who cares if they sound British, American, or Russian?

Now Bryan, you might say, that’s the ancient and medieval world. Chernobyl takes place in the 1980s! We know what Russian people sound like speaking modern Russian and modern English! I certainly can’t argue with that. The point of these musings though, I suppose, is to observe that all our historical media, from the third millennium BC to the third millennium AD, serve simply as projections. They are not snapshots, nor will the ever be; they are like shadow puppets dancing on a wall, and to me at least, language will never be on the list of things I think needs to be shown as clear as possible. Perhaps this is needlessly defeatist; it is often my own addendum that just because we’ll never get that perfectly clear picture of history doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. Perhaps, once again, it’s selfish; I like seeing certain eras of history depicted in certain styles. Either way, all I know is that, when it comes to telling stories in history, I don’t mind if, now and then, a little something gets lost in translation.