The third year of Concerning History has come to a close, and in what has become our longstanding tradition (do we get to use ‘long standing’ now? I think so!), our indomitable staff reflected on the noteworthy anniversaries that have come and will come this year. As this year also hosts the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, we’ve decided to focus on some other anniversaries that are not guaranteed that same level of surely ubiquitous coverage. As always, we can only expose the tip of the iceberg here, so if there are any commemorations we couldn’t discuss, feel free to add your own in the comments below!

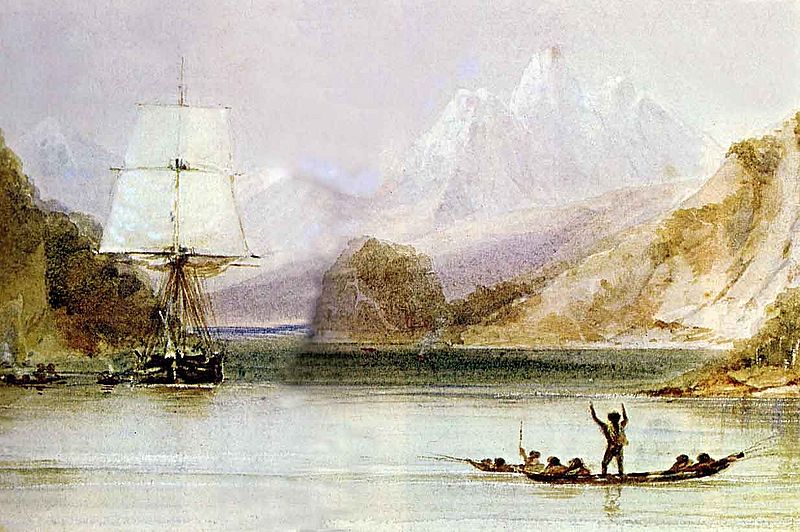

1820: Launch of the H.M.S. Beagle

Heather Clancy

Launched on May 11, 1820 at the Royal Navy’s dockyards in London, the H.M.S. Beagle would go on to become one of the most significant vessels in world history. After Beagle’s conversion from a ten-gun brig to a bark in 1825, the ship departed on its first mission: surveying the South American coast under the command of Lieutenant Pringle Stokes. Three years into his command of Beagle, Stokes endured a severe bout of depression. Succumbing to his disease, Stokes attempted to commit suicide by gunshot on August 1, 1828. To his great misfortune, however, Stokes survived the shot and lived another 11 days until he finally died of gangrene caused by the festering bullet still lodged in his brain.

Lieutenant Robert FitzRoy was next to take command of Beagle, and it would be he who commanded Beagle’s second voyage when she set sail in 1831 with 22-year-old Charles Darwin aboard as naturalist. In this second Beagle voyage, Darwin took part in a massive effort of longitudinal surveying via global circumnavigation. Along the way, Beagle participated in the British capture of the Falkland Islands from Argentina, furthering a centuries-long game of territorial tug-of-war. Darwin’s Journal and Remarks, published in 1839, spanned his time on Beagle for its 1831-1836 mission. The account hints at Darwin’s emerging ideas about evolution: his curiosity about finch beak diversity across geographic regions is like the first historical domino is a long line that passes through his revolutionary book On the Origin of Species (1859) and onto the countless casualties of that bastardization of his theory known as social Darwinism. After the 1831-1836 voyage, H.M.S. Beagle would sail for one more mission before being retired. In 1870, Beagle was sold for scrap after 50 exciting years of service to the British Empire. Her history spans thousands of miles and a surprisingly wide swath of British and world history, and its one that should not soon be forgotten.

– – – – – – – – – – –

Footnote: Readers might be morbidly interested to learn that FitzRoy, like Stokes, would in 1865 commit suicide. Surveying can be grim business, folks…

Recommended Reading: The Voyage of the Beagle: The Illustrated Edition of Charles Darwin’s Travel Memoir and Field Journal, by Charles Darwin

1870: The Fifteenth Amendment is Ratified

The Civil War era sesquicentennial marches on! On March 30th, 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was formally added to the U.S. Constitution as the last of the Reconstruction Amendments. The text of the amendment is remarkably simple and contains just two sentences: the first protecting the right to vote regardless of race, color, or previous status of servitude, and the second empowering Congress to enforce the amendment by future legislation. In many ways, the amendment’s ratification marked the apex of the radical experiment in interracial democracy that was the Reconstruction era. Many liberals believed that protecting the franchise was the last step that the federal government could—and should—take to protect freedmen. In the years that followed, reactionary ex-Confederates and Ku Klux Klanners across the South undermined the amendment’s protections, often violently, while the will of Congress (and the Executive) to address these assaults on democracy wavered. However, for an ever-so-brief moment, the amendment helped elect more Black congressmen than practically the next century combined. 2020 is a fitting year to reflect on the amendment’s lasting legacy, as more African Americans are currently serving in Congress than ever before. Moreover, voting rights nationwide face nearly unprecedented headwinds today in unbridled gerrymandering, voter suppression, and creeping authoritarianism, not to mention a global pandemic that has already thrown two statewide elections into chaos and threatens to imperil the ever important presidential election this fall.

Recommended Reading: The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution, by Eric Foner

1920: America’s First Dry Year

1920: America’s First Dry Year

Bryan Caswell

January of 1920 brought with it the official beginning of Prohibition in the United States, banning the manufacture, distribution, and sale of alcohol under the 20th Amendment to the Constitution. The next thirteen years would see an entire legendary culture of bootleggers, gangsters, and speakeasies rise to fame against the backdrop of the Roaring Twenties and, ultimately, the Great Depression. It has always astounded me that progressives could have pulled off such a sweeping victory as to ban alcohol, through constitutional amendment no less, but the failure of Prohibition may be the more notable event. Now, one hundred years later, Prohibition is infamous, rightly or wrongly, as an example of big government run amuck, the inevitable failure of total proscription, and the public’s undying love for the west’s sanctioned drug of choice.

Recommended Reading: Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, by Daniel Okrent

2000: Bush v. Gore

Kevin Lavery

We’re now 20 years on from one of the biggest fusterclucks in U.S. electoral history. With an unimaginably close margin and a significant number of ambiguous ballots, the U.S. Supreme Court took up the case of if and how to proceed with a recount of the 2000 presidential election ballots. While the Court agreed 7-2 that the Florida Supreme Court’s decision to order recounts in certain counties was effectively a violation of the 14th amendment, it split 5-4 along political lines to decide that the state court had inadvertently created new election law in contravention of its role and that no recount could proceed in time for the federal deadline. Would the results have changed the election? Perhaps not, but because of the process, we have no way to know the voters’ intent. Worse, the Supreme Court established new precedent to intervene in the elections process to determine that it was better for states to provide flawed results rather than find a way to ensure democractic legitimacy. It’s also an illustration of how poorly the winner-take-all Electoral College reflects the will of the voters. Given that both parties will heavily scrutinize this year’s presidential election, and one candidate will inevitably claim fraud without evidence even if he wins (as happened in 2016), states will need to ensure cast-iron voting procedures to guard against the ambiguity of hanging chads or manipulated results. This is a challenge under ordinary circumstances, but under pandemic conditions, failure to plan for the practice of American democracy could destroy its remaining legitimacy (see Wisconsin’s primary). And even bad governance should care about the appearance of legitimacy.

the Court agreed 7-2 that the Florida Supreme Court’s decision to order recounts in certain counties was effectively a violation of the 14th amendment, it split 5-4 along political lines to decide that the state court had inadvertently created new election law in contravention of its role and that no recount could proceed in time for the federal deadline. Would the results have changed the election? Perhaps not, but because of the process, we have no way to know the voters’ intent. Worse, the Supreme Court established new precedent to intervene in the elections process to determine that it was better for states to provide flawed results rather than find a way to ensure democractic legitimacy. It’s also an illustration of how poorly the winner-take-all Electoral College reflects the will of the voters. Given that both parties will heavily scrutinize this year’s presidential election, and one candidate will inevitably claim fraud without evidence even if he wins (as happened in 2016), states will need to ensure cast-iron voting procedures to guard against the ambiguity of hanging chads or manipulated results. This is a challenge under ordinary circumstances, but under pandemic conditions, failure to plan for the practice of American democracy could destroy its remaining legitimacy (see Wisconsin’s primary). And even bad governance should care about the appearance of legitimacy.

Recommended Reading: Bush v. Gore 531 U.S. 98 (2000)