by Bryan & Heather

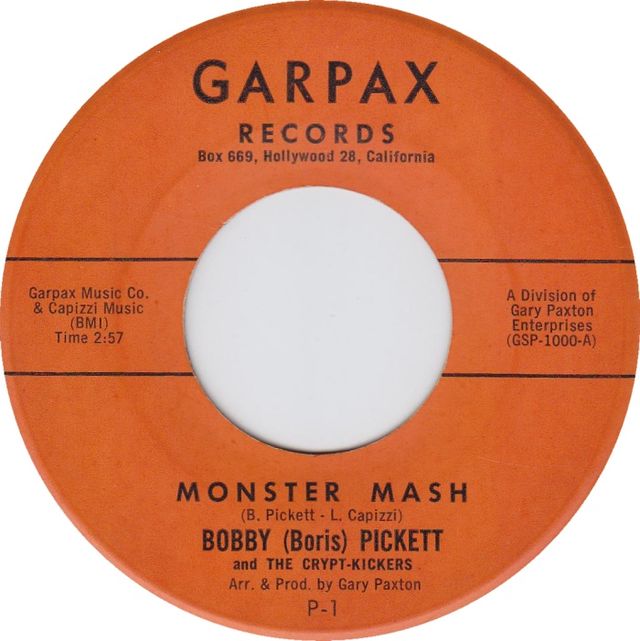

October 1 brings with it Heather’s favorite season, and so as we do every year, we got out all our Halloween decorations, acquired some new ones to keep it fresh, and set to decorating our temporarily-haunted abode to the spooky music of a slew of Halloween playlists. This year, however, we couldn’t help but really notice how many of these songs sounded, well, vintage. There were the perennial classics like “Monster Mash” and “Purple People Eater,” of course, but it just seemed like more often than not, the music playing in our speakers sounded closer to when our parents were born than even we were, let alone 2022. We couldn’t help but wonder–why? What was it about the 1950s and ‘60s that gave rise to such an outpouring of musical Halloween spirit? To our surprise, there really hasn’t been much ink spilled over the foundations of modern Halloween music on its own. Playing a few hunches, however, we dove into piecing together our own speculation on the subject.

The first and most obvious inquiry was brushing up on the history of Halloween itself. While it may have begun as all manner of pre-modern Celtic and Christian rituals celebrating either the harvest, the passage of souls, or both, the holiday we know today as Halloween really got its start in the middle decades of the twentieth century. The disparate traditions of America’s Irish, Scottish, and other Catholic immigrants combined with the ascendant capitalism of the United States to produce an increasingly commercialized, secular holiday focused on costumes, trick-or-treating, and all things spooky or autumnal. In what seems too close to be a coincidence, much of this popularization of Halloween took place concurrently with or just after the classic run of monster movies produced by Universal Studios in the 1930s that inform so many of the foundational monsters of the holiday. Whichever informed the other was too academic an undertaking for our current efforts, but whatever the case, it was clear that by the 1950s, America was culturally primed for an explosion of Halloween spirit.

This led us right into our second and third hunches. It’s hard to discuss anything regarding American society and culture in the second half of the twentieth century without mentioning the Cold War and the Counterculture, and so it proved with Halloween music. Horror is often used as a “safe” expression of society’s fears and insecurities, and it’s hard to imagine a more insecure time in the last hundred years than the beginning of the Cold War, decolonization, Civil Rights movement, and the gender liberation struggle. At the same time, horror can also be used subversively to poke fun or criticize the mainstream. Thus, whether you were a member of the postwar middle or upper class scared of the changing values and demography of the nation or a scrappy student railing against the stuffy expectations of traditional society, Halloween–and Halloween music–could have offered an inviting outlet in the guise of celebrating a fun, “harmless” holiday.

All our speculation, however, must be taken with a pinch of salt, especially considering what became more and more clear as we researched: when you get right down to it, the actual relationship between many of these songs and Halloween is tenuous at best, existing only because we say it exists. Unlike Christmas, when songs seem nearly pathological about mentioning their connection with the holiday and its iconography, Halloween songs often just include monsters and/or mystical topics, but no explicit holiday messaging. Some, like the famous Glenn Miller Orchestra song referenced in our title here, seem to have even been co opted by contemporary audience and playlists that think anything that mentions the word “magic” is related to Halloween. Even such mainstays as “Monster Mash” and “Purple People Eater” seem, on second or third listen, more akin to the zany nonsense songs written for pre-schoolers to sing together during circle time than any conscious effort to celebrate Halloween. Yet, whether fittingly or ironically, these songs have become so identified with Halloween in the twenty-first century that the original intentions of their authors are almost irrelevant.

Clearly this subject invites much more in-depth examination from those with more time, resources, and expertise than we, but we feel somewhat confident that these classic, beloved Halloween tunes can be situated within the wider cultural context of the 1950s and ‘60s–postwar prosperity, exploding popular culture, Cold War anxiety, and subversive counterculture like rock ‘n’ roll that, while perhaps off-color for the time, appears ultimately tame compared to what followed it. Regardless, as with so many things good and bad in modern America, it seems the roots of how we experience this culture mainstay are located in the specific expressions of the travails of yesteryear.

One reply on “That Old Black Music: Exploring the Halloween Tunes of Yesteryear”

I would also say televisions rise in that era ment kids saw tv broadcasts of old monster movies as well as pulp magazines (pre comics code lol).