by Bryan & Heather

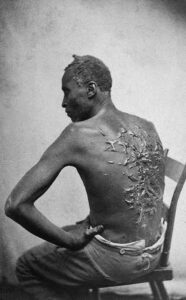

An intriguing movie trailer aired in the fall of 2022. At first, it appeared to be simply another Civil War period piece, this time featuring an older Will Smith as a slave attempting to gain his freedom by escaping through Louisiana swamps towards Union forces following the Emancipation Proclamation. Yet in its final moments, this trailer revealed that Will Smith’s character is actually supposed to be the subject of one of the most famous photographs of all time, showing an enslaved man who had been flogged a horrific number of times. Our attention thoroughly engaged, we could think of no better way of commemorating the 160th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation by viewing Emancipation.

While some elements of society still cling to myths that the antebellum South’s system of human bondage was somehow not so bad or even more humane than wage labor in other regions of the United States, the horrors of slavery have thankfully become more or less commonly accepted among the 21st century public, not least through such modern visual depictions as Amistad and 12 Years a Slave. The question, then, becomes whether a new slave narrative can add anything unique to the public’s perception of the peculiar institution. Here, Emancipation largely delivers. The film’s opening sees Will Smith’s Peter torn away from his family not through being sold by his master but through the conscription of his labor in service of the Confederate military–a refreshing acknowledgement of this reality of a logistical system that allowed the Confederacy to punch above its weight on paper. In Peter’s quest to reunite with the wife and children he was torn away from, Emancipation soon evolves into not so much a litany of slavery’s horrors (a la Twelve Years a Slave) but of blacks’ acts of personal resistance to those horrors, from self-mutilation to the act of running away to the varied motives in enlisting in newly-formed United States Colored Troop units. By the time the film closes and Peter finds his family (miraculously still together in a rare unblemished happy ending), Emancipation stands as a testament to the fortitude of all those enslaved persons who took it upon themselves to force the war for union to become a war for freedom.

All that said, Emancipation is not quite a flawless period piece; a number of odd decisions serve to, if not detract from its core theme, muddy its presentation and historical context. One of the more striking visual touches is the film’s de-saturation, giving it the appearance of taking place entirely within the palette of a Victorian daguerreotype. While a neat trick, that ultimately turned out to be all it was; our speculation that color would return to the world once Peter’s ordeal ended proved unfounded (though arguably the rest of their lives under Reconstruction and Redemption would be no less an ordeal). From an historical perspective, the choice to emphasize white Northern racism during Peter’s time in the USCT values hammering home a by-now commonly recognized point while sacrificing larger points about the cause of preserving democracy–indeed, the only fighting motives ascribed to Northern whites in the entire film are greed and power. Peter’s personal motives are also somewhat odd in presentation; his unshakeable Christian faith sustains him throughout his harrowing swamp escape and charge against the Confederate batteries at Port Hudson, Louisiana, yet the fact that this faith is itself a religion forced upon his people by their enslavers is never mentioned.

Despite these peculiarities, however, one could do far worse than Emancipation in search of a modern slave narrative. It may not quite reach the heights of other classics, but it certainly is a valuable contribution to the genre in its own way. At the very least, it deserves credit for bringing the battle of Port Hudson to the big screen, and for those who can stomach films of this kind, it is well worth a watch.