Buck, Rinker. The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

In 2011, writer Rinker Buck and his brother Nick embarked on an epic journey to cross the Oregon Trail in a covered wagon, staying true to the original route(s) whenever possible. Part history, part travel guide, and part personal introspective, his book mirrors the journey it chronicles: part living history experience, part ambitious adventure, and part family drama. All of this on top of being painstakingly thorough in the historical information it conveys and hilariously entertaining in its events and commentary.

In 2011, writer Rinker Buck and his brother Nick embarked on an epic journey to cross the Oregon Trail in a covered wagon, staying true to the original route(s) whenever possible. Part history, part travel guide, and part personal introspective, his book mirrors the journey it chronicles: part living history experience, part ambitious adventure, and part family drama. All of this on top of being painstakingly thorough in the historical information it conveys and hilariously entertaining in its events and commentary.

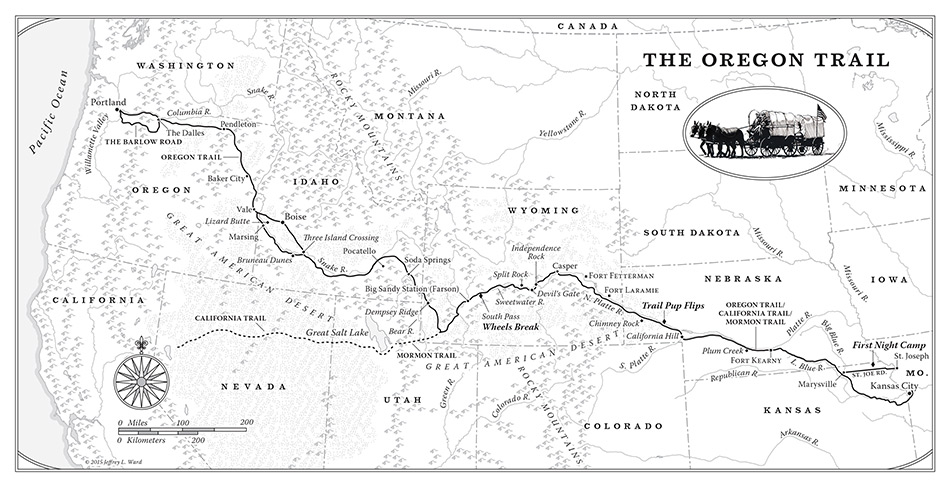

The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey recounts their trip, from packing and outfitting their rig to chasing mules in the desert wearing house slippers to overcoming broken wheels in the middle of nowhere. Buck also goes into great detail with the technical aspects of the crossing in covering mules, wagon design, landmarks, and trail politics. The parallel journeys of his own crossing and those of earlier pioneers offers a unique opportunity to cover these logistics and more. Buck’s modern crossing also allows him to cover the politics of Oregon Trail commemoration and preservation today, as the ability to find a clear path through vast ranchland and hospitality among Mormons becomes all the more meaningful.

Throughout the book, Buck notices a theme that transcends his historical and modern commentary: the irony and mythology of “rugged individualism” and the “pioneer spirit” in the West. Buck, like most of us, grew up learning (through history classes, movies, and politics) that the American West is a place where individuals can rise and fall on their own accord. Here, on the frontier and far away from “civilization,” is where you can rely only on good luck and gumption to survive and thrive. Buck shatters this myth, outlining how it was never true and remains a myth today. His case is strong: the transformation of the West was only made possible by massive government and private spending pumped in from the East. It was this spending that paid for soldiers, mines, railroads, and ranches in the 19th century and Civilian Conservation Corps units, National Parks, and dams in the 20th. Today’s Western tourist, agriculture, and resource extraction economy was built and revitalized by these programs. Here, too, the parallel journeys displayed in the book offer a perfect lens to explore this topic.

While this parallelism helps facilitate a greater historical understanding of 19th century westward migration, it also hinders it in one significant way. Buck’s journey was that of two men and a dog; the migrations of yonder were more akin to moving armies. To his credit, Buck writes extensively about the communal nature of the trail, citing many examples of how it would not have been possible without many people pitching in throughout the journey. Yet all of this is somehow undermined by Rinker and Nick completing the trip mostly on their own. Of course, they had the advantage of being able to get rides from friendly strangers when they broke down and carrying less overall weight seeing as they were not uprooting their lives long term. Even when these advantages are weighed and the actual history of massive trains explored, the sheer solitude of the modern crossing prevents a holistic understanding of the journey that is otherwise illustrative everywhere else.

For all of its expansive historical detail, The Oregon Trail does suffer from one major oversight: a relative paucity of details on the indigenous experience with the trail. Buck doesn’t ignore Native Americans entirely, but instead speaks of them within the context of the Whitman Mission (and its eventual destruction at the hands of the Cayuse) and the 1866 Fetterman Fight (or Fetterman Massacre, which is how Buck tellingly names it as have most history books). In both cases, native people are treated as obstacles and threats to the settler-conqueror protagonists. Little to no effort is made to include indigenous voices or perspectives. To be fair to Buck, this is not the story he set out to tell; a totally different work incorporating native voices and written by an indigenous author would better fit the bill. But for someone who spends an entire chapter talking about the historical legacy, breeding practices, pedigrees, and behaviors of mules, it is a bit disheartening that Buck opted to steer clear of a massive community of people who greatly shaped the course and experience of the trail and were equally shaped by it.

One final note involves the author-protagonist’s long ruminations on his relationship with his father throughout the book. Buck is haunted by the ghost of his father, who inspired in him a love of rugged travel decades ago when he took Rinker and his siblings on a covered wagon trip from their home outside New York City to Gettysburg in 1950. Normally I’m not that interested in this kind of personal introspection (I’m still not), but every good travel memoir must talk about the trip, the land, and the traveler. I love the first two and Buck does a pretty bang up job covering them; I’ll learn to put up with the latter to complete the triumvirate. Moreover, I’d like to think that Buck’s reflections offer a deeper understanding of the psyche of the pioneers. You think that men growing up in a socially conservative patriarchal society where one’s livelihood relied almost entirely on their ability to provide for their family didn’t have some latent daddy issues and that walking for months across an often desolate landscape didn’t lead their minds to dwell on them? Come on.

The Oregon Trail is definitely one of the most unique reads I’ve encountered in a while. Simply put, there’s a lot to like about The Oregon Trail. You’ll learn a lot and you’ll laugh even more. Even accounting for its shortcomings, I would highly recommend a read.