Last October, the state of Virginia kicked off its commemoration of the 400th anniversary of several key events in its early history. The festivities began with the anniversary of the founding of the House of Burgess–the first known legislative body in what would become the United States–and will continue into this year with the anniversary of the arrival of African slaves to Old Point Comfort, now Fortress Monroe.

This latter event, and the year 1619 more broadly, has traditionally been pointed to as the beginning of the African story in America. It’s a powerfully symbolic year that has been accepted into the American canon, a rarity for events and milestones that shed light on the nation’s darkest histories. As such, museums and historical sites across Virginia–including Historic Jamestowne, the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, the Hampton History Museum, and Fort Monroe National Monument–have all planned special events and exhibitions to educate the public about the historic event and its legacy throughout the following four centuries and beyond.

Yet focusing on 1619 fails to properly contextualize the beginning of the African American story in what would become the United States. The way that the 1619 arrival is traditionally taught in American schools and consequently understood in the American psyche (if it is remembered at all, that is) goes something like this:

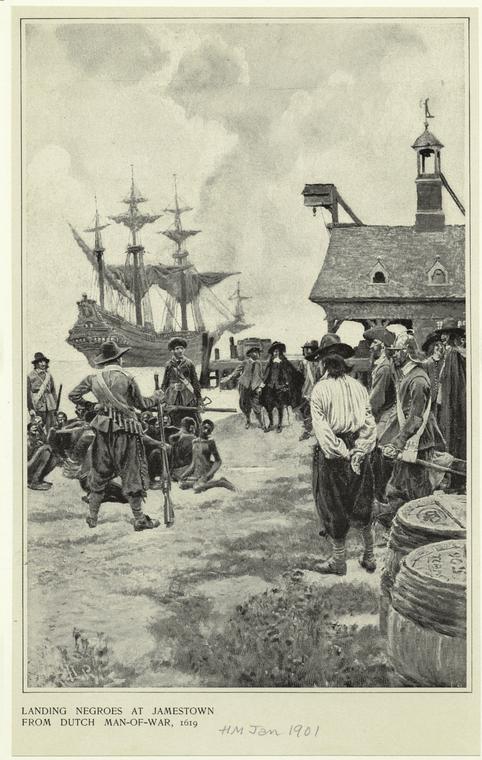

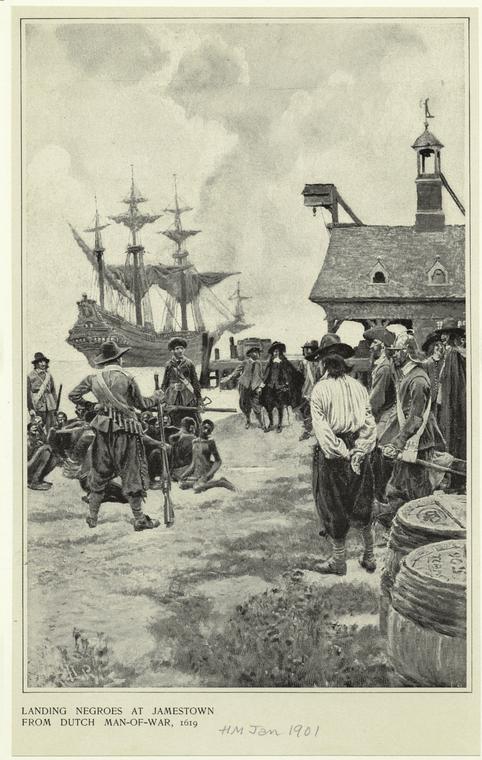

In August 1619, “20 and odd Negroes” disembarked from the White Lion, a Dutch man-o-war, and set foot in the English colony of Virginia. They were bought by English colonists and soon put to work in the struggling colony, the first of what would become many slaves to arrive and subjected to forced labor in Virginia and other English colonies, and eventually the United States.

This narrative is historically problematic for a number of reasons. First, the White Lion is described as a Dutch ship, providing an initial, notable distance between the English colonists and the sin of slavery. The implication is that the English settlers did not necessarily want slaves or slavery (proponents of this narrative might also point to the fact that slavery was not codified into early Virginia colonial law), but that a Dutch ship had introduced them to slavery. English settlers therefore play a curious, perhaps naive Adam to the Dutch sailors’ guilty and tempting Eve in this vignette of one of America’s original sins.

Of course, this myth ignores the fact that the English were very active participants in the transcontinental slave trade at this point, using African slaves in Bermuda for at least three years earlier as well as raiding enslaved African bounty from Spanish and Portuguese ships as Sir Francis Drake had in 1586 before he landed at Roanoke the same year. Even earlier, English merchant Sir John Hawkins engaged in four separate slave-trading missions during the 1560s. To further spoil the myth, it is also worthwhile to point out that the White Lion was in fact an English ship afterall–it was merely carrying a Dutch letter of marque in order to engage in piracy with the Spanish and Portuguese, which is how the crew came to carry its infamous cargo in the first place.

Second, the traditional myth does nothing to explore or even suggest an exploration into the backgrounds of the twenty Africans who arrived in Virginia in 1619. Setting foot on the Virginia peninsula’s sandy soil was only the latest event in what must have been a series of tumultuous lives up until that point. The men and women likely belonged to a group of Kimbundu-speaking peoples living in the Kingdom of Ndongo in present-day Angola. They may have lived in rural communities there raising cattle or growing sorghum and millet, or lived in the urban center of Angoleme among its population of 30,000. Throughout 1618 and 1619, the African mercenary group called the Imbangala allied themselves with the Spanish-ruled Portuguese governor of Angola, Luis Mendes de Vasconçelos, and together embarked on a series of devastating campaigns in the area. During the period of violence and political instability, the future Black Virginians were captured and sold to Portuguese captain Manuel Mendes da Cunha of the São João Bautista, who held an asiento (license) from Spanish investors in Seville to sell his human freight in the Spanish port of Vera Cruz in present-day Mexico.

On the journey, the “cargo” were packed and cramped into unspeakably inhumane conditions that so characterized the Middle Passage. Yet when da Cunha arrived in Vera Cruz, he was short by dozens of slaves. Invariably, many died in transit. Around 50, however, were taken when the São João Bautista was attacked by the English privateers Treasurer and White Lion, the latter of whom would successfully trade its human cargo in Virginia. By the time they arrived in Virginia, the new enslaved residents had experienced cataclysmic political violence in their homeland, the confines of a colonial Portuguese slave jail, the unthinkable horror of the Middle Passage, naval combat on the High Seas, and transit to world and culture entirely unknown to any of them. Overlooking this broader context ignores the forces that shaped the course of slavery on both sides of the Atlantic. The first Black Virginians’ lives did not begin in 1619 and neither did American slavery’s.

Perhaps most importantly, the focus on 1619 commits the interpretive sin that so many lessons and narratives on African American history fall prey to: failing to show Black Americans as active participants in their own history. For a long time, the challenge that faced historians of African American history was legitimizing the intense violence and persecution that Black Americans faced from bondage and whippings to segregation and lynchings and beyond. In many ways, historians are still trying to fight this battle with the American popular understanding of history. Yet even when historians might emerge victorious from this encounter with their own understandings and those of their audiences, they often fail in the step of depicting Black agency.

According to the canon of 1619, enslavement happened to the Africans. Moreover, what little critical analysis on this historical encounter that occurs in the classroom and at historical sites usually focuses on what the White, English inhabitants of Virginia would have thought about their new enslaved neighbors, and not what the traumatized newcomers might have thought about their new home. Nor does early colonial history usually discuss the many ways in which slaves resisted their bondage through insubordination, flight, and even violence. Fortunately this narrative is changing thanks to a long, national conversation about how we interpret and discuss our national story and myths. But binding ourselves to 1619 as the beginning of the African American story does little to help this narrative battle and far more to impede its progress.

Nor is 1619 a historically appropriate date to commemorate slavery’s beginnings in America–in fact, it misses the mark by nearly a century. Instead, our national focus for this milestone should instead be trained on the year 1526, four decades before even the first attempts at English settlement in North America at Roanoke.

In late September 1526, Spanish sugar planter and prospective settler Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón established the first known European settlement in what would become the United States somewhere in coastal Georgia or the Carolinas. The settlement, named San Miguel de Guadalupe, came at the conclusion of a months-long journey to try and found a Spanish settlement in continental North America. During the journey, one of the ships loaded with supplies from Spanish Hispaniola ran aground and lost nearly all of its cargo. Moreover, the late founding date prevented the settlement from planting a successful crop before the weather turned unfavorable. Without necessary food and supplies, the settlement was virtually doomed from the start. Soon, due largely to starvation rations, mosquitos, and unseasonably frigid weather, members of the mission began falling victim to disease, including Ayllón, who died a few weeks after San Miguel de Guadalupe was founded.

But among the settlement’s inhabitants were as many as 100 African slaves brought from Hispaniola. These are the true first Black Americans–predating the English colonists at Jamestown by nearly a century. Moreover, their story indisputably presents them as active participants in their own fates as well as the fate of the first European settlement in the United States.

Following the death of Ayllón, the starving settlers began to feud over leadership and struggled to obtain food. One group of Spaniards ransacked a nearby Guale village for food, provoking retaliation that resulted in the deaths of many Spaniards. Taking advantage of the chaos, the African slaves revolted, burning down the home of a Spanish leader and fleeing San Miguel de Guadalupe to live among the Guale. The remaining Spanish survivors fled back to Hispaniola in the weeks that followed. America’s first Black inhabitants had therefore orchestrated the continent’s first successful slave revolt, hammered the final nail in the coffin of the first European colony in America, and been the first fugitive slaves in what would become a centuries-long tradition of Black slaves fleeing bondage and integrating into native American Indian-African gullah colonies along the Atlantic seacoast. As it turns out, America’s first true Black inhabitants were a microcosm for the next several centuries of African American history.

Suffice it to say that the events of 1526 are a far more appropriate marker for the beginnings of African American history. Not only do they more accurately reflect the transnational realities of the Atlantic world at the time, but they also portray their participants in an unmistakably active role.

So what should we do with 1619? None of this is to say that 1619 and its connection to slavery should be relegated to the dustbin of history. Rather, this date has important symbolic as well as historical significance for our national history. Indeed, 1619’s significance as both the date for the founding of the House of Burgess and the arrival of the Virginia colony’s first slaves holds enormous potential in portraying the duality of American liberty. At the same time that the first American legislators met, representing the beginning of a long and nation-defining tradition of self-governance, members of that same body were dealing in human flesh as part of a nascent plantation system that would define much of the forthcoming nation. The dueling themes of liberty and tyranny at the personal and national level were there from the beginning of the nation.

Moreover, the 1619 date serves as an important touchpoint for the millions of Americans that grew up learning this narrative to expand their understanding of the long(er) history of slavery in America. Luckily, we have not missed a grand opportunity to unroll this more fitting narrative–the 500th anniversary of the San Miguel de Guadalupe founding and rebellion are in 2026. That gives the historical community about seven years to update the narrative around slavery and African Americans’ beginnings in the United States. What better opportunity to start that conversation than the commemorations of 2019?