We all have our pet historical time periods. Whether we come to them in seminal moments as children or discover a newfound appreciation for them as adults, there’s always something beyond the basic facts, something ahistorical that resonates and calls us to patronize those particular eras more than others. You might call this the ‘essence’ of the period or subject, such as each individual understands it, and while this affection can lead people to become avid students of history, they can also contribute to all the implicit biases that make the field of history so perilously subjective. I’ve recently noticed a manifestation of my own biases that may sound ridiculously petty, but nonetheless plays a key role in my consumption of history: the weather.

We all have our pet historical time periods. Whether we come to them in seminal moments as children or discover a newfound appreciation for them as adults, there’s always something beyond the basic facts, something ahistorical that resonates and calls us to patronize those particular eras more than others. You might call this the ‘essence’ of the period or subject, such as each individual understands it, and while this affection can lead people to become avid students of history, they can also contribute to all the implicit biases that make the field of history so perilously subjective. I’ve recently noticed a manifestation of my own biases that may sound ridiculously petty, but nonetheless plays a key role in my consumption of history: the weather.

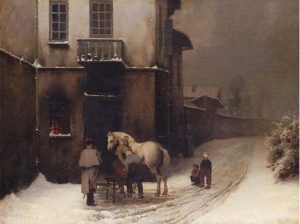

In my opinion, weather, climate, even time of day are crucial for setting the scene of my historical musings. Naturally, all of these things whither in the cold light of more academic, analytical history; when you’re reading an article breaking down trade patterns in the western Indian Ocean, there’s not much room for flights of fancy. Yet when in the course of the day I happen to reflect on some time period, perhaps as a side effect of a recent video game or movie, I definitely tend to associate certain conditions with certain eras. The biggest culprit here for me is the Roman Empire. The height of the Republic and Principate around the turn of the first millennium is invariably bathed in the bright sunlight of the late morning and noon; Late Antiquity is dusk on a winter evening, hoarfrost covering the grass as fitful snowflakes dance in the light of a solitary watchman’s torch; the centuries following Rome’s final collapse are covered in rain and mist as thick as the curtain that obscures so much of that period from our eyes.

Many other periods and subjects receive this treatment, and I know that I’m not the only one who does so. When I first discussed this post with Kevin, he was immediately on board, mentioning that for him Victorian England is perpetually a foggy night, prime for Jack the Ripper to step out of a murky alley lit by gaslamp. It’s hard to think of the American West in anything other than the blistering, dry heat of a midday summer’s sun; the British Raj of the twentieth century is nothing without its own summer afternoons, these laced with oppressive humidity and filled with the sound of lazy ceiling fans.

So what’s the point of all this? Am I just taking this opportunity to indulge in vivid imagery? Show off my own writing skills? Maybe a little bit, but I also think that examining how we consume and perceive of history inside our own minds is the best way to identify and fight our biases. Clearly, I view the Roman Empire as a great edifice of history; that may be accurate in some respects, but I shouldn’t let it blind me to its brutality or to the vibrant peoples that succeeded it. Ultimately, all these stylized images are fundamentally romanticized, and as many of us have remarked in the past, romanticization is the death of good history. Does that mean I’m going to try to stop? No, not even if I could, but it does mean that from here on out, I might give a knowing chuckle when these images appear, fully realized, in my head.