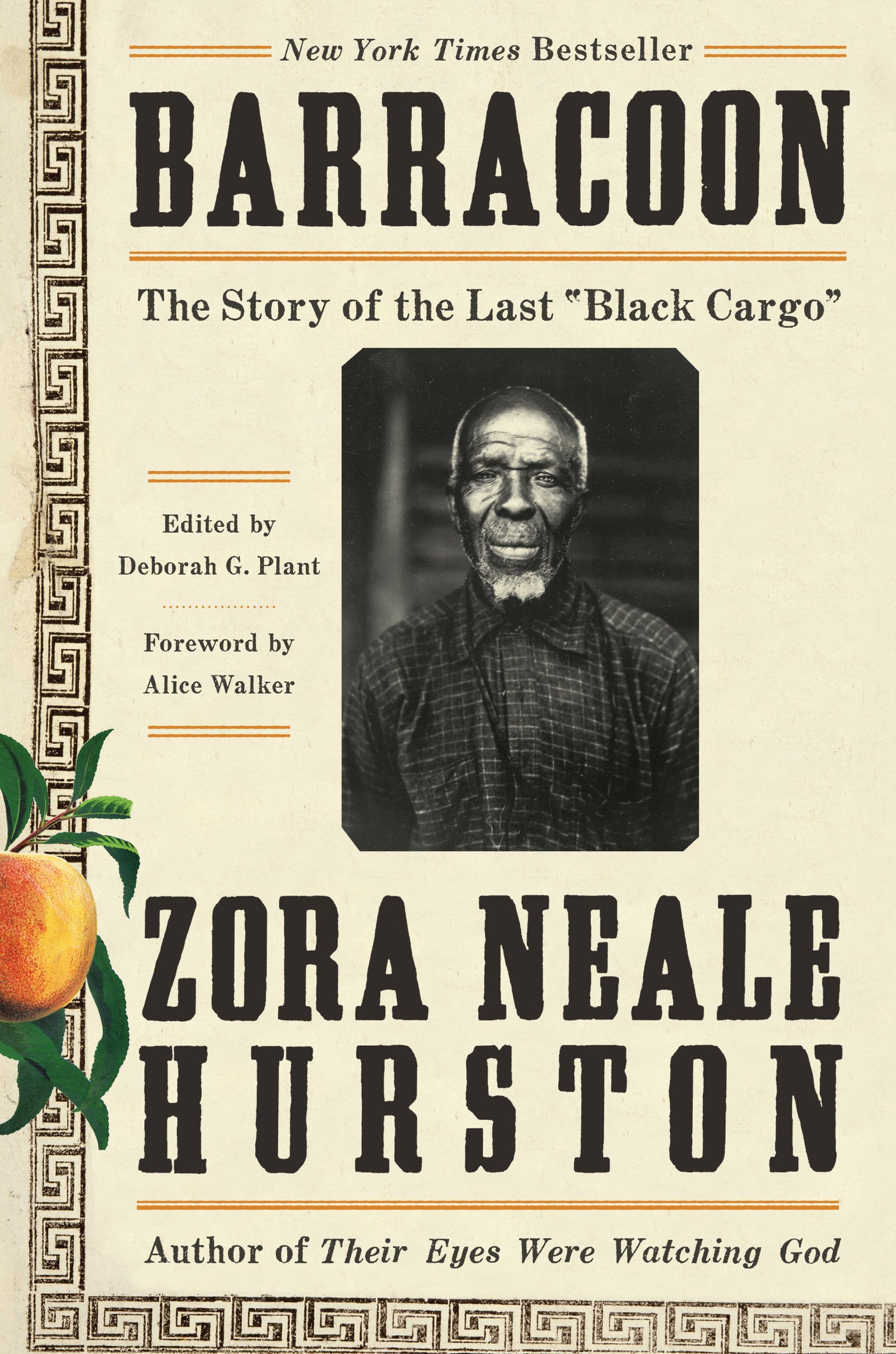

Hurston, Zora Neale. Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.” New York: Amistad, 2018.

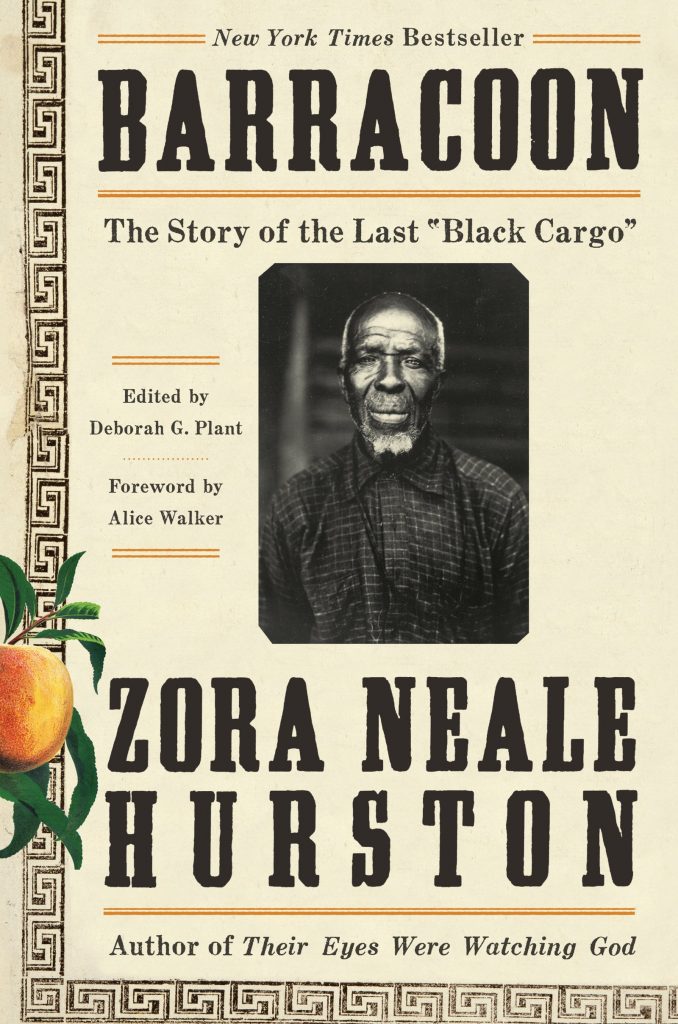

Nearly a century ago, a young, not-yet-famous Zora Neale Hurston traveled to the small community of Africatown (now Plateau) just north of Mobile, Alabama, where she would interview a local man named Cudjo Lewis. Lewis had been born Olaule Kossola in West Africa around 1841 before being kidnapped by warriors from the Kingdom of Dahomey during a raid on his village. Lewis was then marched to the sea where he was sold to an American ship captain, who took him and 109 other slaves to Alabama aboard the Clotilda in 1860. After emancipation, Lewis was one of the founding members of Africatown, a community established by the survivors of the Clotilda. Zora Neale Hurston’s Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” tells Lewis’s story in his own words.

There are few things to know before reading Barracoon. First and foremost, Barracoon is more an oral history of Cudjo Lewis rather than a biography. The vast majority of the book’s text is taken up by Lewis detailing events and details of his life in his vernacular language. Hurston herself only rarely interjects in the pages, but we can only speculate as to how much she steered Lewis’s retelling and prodded for more detail off the page. Hurston does provide useful documentation and information in the introduction and appendices that help contextualize his story. Additional information on Hurston’s role in documenting Lewis’s story is also included by editor Deborah G. Plant. However, the “meat” of Barracoon is Lewis recounting his life story much like a griot from his native land.

Second, Barracoon almost did not happen. Zora Neale Hurston interviewed Lewis in 1927 and 1928, and while Hurston and earlier writer Emma Langdon Roche both wrote contemporarily about Lewis, Barracoon remained an unpublished manuscript for nearly a century. Publishers at the time balked at taking up the story, insisting that Hurston translate Lewis’s vernacular and make the narrative more appealing to a broader (read: Whiter) audience. Hurston refused. Only in 2018 did Barracoon finally go to print, though some material had previously been included in an earlier biography of Hurston. The full story of Barracoon’s long road to publishing is included in the forward and afterward.

While the story of Barracoon is of course interesting, it pales in comparison to the story within Barracoon. Cudjo Lewis belonged to a relatively small group of individuals who survived the Middle Passage, slavery, and the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction years. He belonged to an even infinitesimally smaller group of individuals who managed to leave behind a written account (even though he himself did not transcribe it–Lewis could not read or write) of their lives.

Lewis’s story is also remarkable for his unique experiences. Lewis speaks extensively about his life in Africa before slavery and often references it later in his narrative as a means of making comparisons between life “in de Afficky soil” and “in de Americky soil.” A slave for about five and a half years, Lewis primarily worked on a barge shipping freight from Montgomery to Mobile. The Civil War began soon after his enslavement and while Lewis heard from others that the war was fought over slavery, he did not believe it at the time: “we wait and wait, we heard de guns shootee sometime but nobody don’t come tell us we free. So we think maybe dey fight ‘bout something else” (61). The war mostly affects Lewis because coffee and sugar become scarce, much to his chagrin.

He eventually learns of the war’s end and his freedom from Union troops who stop his barge in April 1865. Lewis and others believe that they are entitled to money from their former owner in order to pay for their passage back to Africa. At the very least, they reason that they are owed land to make a new home if they cannot return to their old home across the ocean. When Lewis asks his former owner for land, he is laughed at. Despite this rebuff, Lewis and others who came over against their will on the Clotilda save their money to buy a parcel of land and call it Africatown, creating an enclave society in the fashion of their native home.

Lewis endures incredibly trying times in the years that follow. He must first live with incredibly prejudice emanating not from local Whites, but from natural-born freedmen who, according to Lewis, “pick at ya all de time and call us ig’nant savage” (69). Lewis outlives his wife and all of his children, one of whom is shot and killed by a Black deputy. Lewis himself is permanently disabled when he is struck by a train, but never receives his settlement money.

Unlike the more popular slave narratives of Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, Lewis’s story does not crescendo towards fulfillment after emancipation. Rather, his life seems to always be one of looking backwards to life in a faraway land he once called home. As Barracoon editor Deborah G. Plant writes, “it is a kind of slave narrative in reverse” (130).

Overall, Barracoon offers much in terms of expanding our understanding of the experience of the Middle Passage, slavery, and emancipation. It also complicates the popular narrative of trans-Atlantic slavery, showing in vivid detail the role that local African kingdoms played in the slave trade as well as the discrimination that Africans faced in America, even from African American freedpeople. While these complications are not revelations for scholars of American slavery and its aftermath, Lewis’s story provides a new source to flush out the narrative. And for a more general audience, Barracoon offers a succinct yet compelling narrative of slavery and its aftermath.