“What was the American Civil War about?”

“What was the American Civil War about?”

This question has bedeviled American historians and, indeed, the American public for over a century. Its battlefields are endless, and, for many people, the answer that you provide determines whether you are a Knowledgeable or Ignorant Person. I’ve certainly been involved in more than my share of skirmishes, so it probably isn’t a surprise to hear me say that I hate this question. What may be surprising, however, is my reasoning. To ask what the American Civil War or any war was “about” is a horrible, meaningless question. It comes so easily to our minds, and we expect history to provide a succinct, easily-digestible answer. When it does not, we tear each other apart in seemingly-endless debates, dismiss conflicts as meaningless, or brush over them in history class. Yet history is a complex business that seldom meets our demands for simplicity, and this is certainly the case when trying to understand any given human conflict. “What was this war about” contains a legion of implicit questions, many of them conflicting and all including their own unique focus. What, then, are we asking when we ask this question?

Underlying Issues – This is probably what most people are referring to when they ask what a war was about. What long-standing issues, be they political, economic, social, cultural, religious, etc., resulted in armed hostilities breaking out between two or more parties? Sometimes these issues can be present for only a short time, and other times they have lurked for decades or even centuries. Examples of underlying issues would be slavery for the American Civil War or colonial sovereignty for the American Revolution. Identifying underlying issues, however, poses a whole host of problems for historians. First and most obviously, the long-term issues that caused a war may not be apparent until sufficient time has passed to allow for somewhat-detached historical analysis. Secondly, the vast majority of historical wars are not caused by what we would today consider acceptable long-term issues. I reflected on this modern cognitive dissonance in Part I of this series (found here). The idea that wars are caused by underlying issues assumes that peace is society’s equilibrium, which is a very modern sensibility that has only been held for the last three centuries if we are being extremely generous. War, conquest, expansion, imperialism, or whatever you’d like to call it has been the default setting for societies for most of history, and so the necessity of an underlying issue for, say, the wars of the Roman Empire seems ridiculous. Finally, while issues are what prime a war’s powder keg, they are not always what set it off, leading to their confusion with…

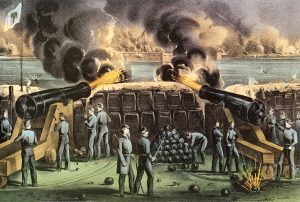

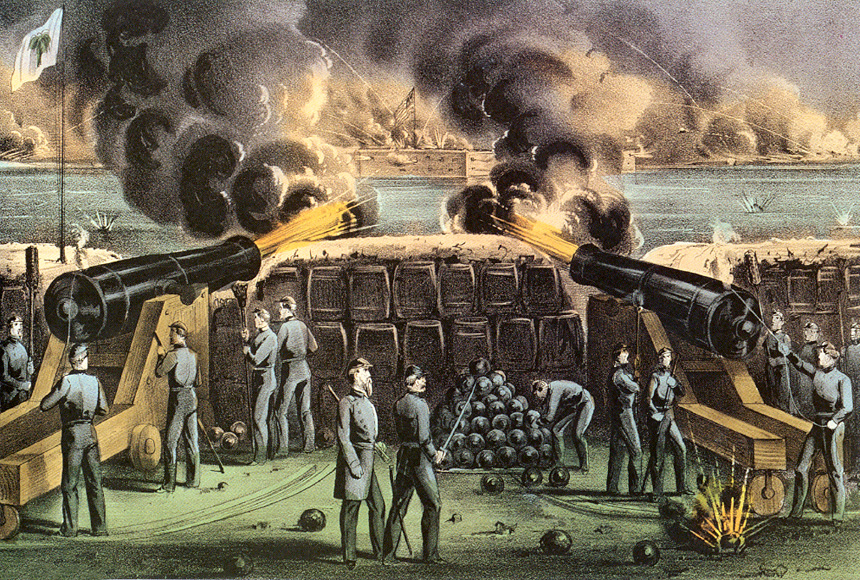

Causality – The intermediate and immediate events leading to the outbreak of war can take on a different form than the underlying issues that have led to them. This can at times lead modern audiences to think that a war is pointless when its spark is seemingly innocuous for the carnage that follows, as in the case of the First World War and the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. It can also lead to a confusion of the issues themselves, as in the case of the American Civil War. That conflict was begun by a cascading chain of events beginning with the secession of seven southern states following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1861 and concluding with the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter, which formally commenced hostilities. Thus a knowledge of the long-term issues is necessary to make sense of the causes of any war (like knowing that the southern states seceded explicitly to protect slavery). Once wars begin, however, a third issue arises…

War Aims & Outcomes – Every state or society goes to war for a reason, but once they are at war, that reason can part ways with the plan for how to win. These war aims, or what a polity hopes to accomplish on the battlefield and at the negotiating table, can be highly influenced by the proximate cause of the war and have become more detailed and complex since the advent of the modern era and formal military thinkers in the vein of Carl von Clausewitz. Thus while the American Civil War was caused by the long-term issue of slavery, the choice of the southern states to secede and the choice of the Federal government to fight them required war aims to focus on thwarting secession, not freeing the slaves. This fact has been misconstrued, willfully or otherwise, by certain parties to argue that slavery actually had nothing to do with the outbreak of the American Civil War. War aims can, and most often do, change as the war progresses. Targets of opportunity present themselves, like the many sideshow campaigns of the First World War, or different strategies are required to decisively win, like with Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation two years into the American Civil War. These changes can understandably add further confusion to what, exactly, that war was about, as can taking the outcomes of war as evidence for why it started. Finally, all these categories are augmented by a different, less-lofty consideration…

Motivations for Fighting – Ever since the advent of volunteer, citizen-soldier armies in the nineteenth century (or perhaps the mid-eighteenth, if we count colonial American militia), the common soldier has had a say in what a war could be ‘about.’ Why were these men signing up to fight, and did those reasons stay the same as they and their comrades gave their lives? While these motives can be influenced by our previous three categories, they are often more prosaic, focusing on notions of honor, duty, family, or other personal considerations. These motives are, of course, highly individual, and one soldier generally cannot stand in for an entire body. Motivations for fighting can go only so far, however, as no matter what soldiers write or say, if they are choosing to fight in a state’s armed forces, they are fighting in support of that state’s war aims. Thus “My great-great grandfather didn’t fight to keep slaves, he didn’t even own any!” has no bearing on the fact that the Confederacy did, which incidentally means that the ancestor in question did, in fact, fight for slavery.

By now, I’m sure you begin to see the problem with flippantly referring to what a war was ‘about,’ and why I will likely pause to collect all of my thoughts before relating a multi-staged answer whenever asked. There are so many opportunities to become confused or to willfully misrepresent historical evidence for the purpose of propaganda. If, instead, we break down any such discussion into these four categories, we can avoid confusion and pursue a clearer understanding of history whenever possible.

2 replies on “The Why of It All, Part II: The Worst Question in History”

It’s always bothered me that saying “slavery was the cause of the Civil War” as many times as possible almost seems like a token of legitimacy when it comes to talking seriously about Civil War history. I mean, it’s correct and it’s a topic that needs to be addressed (especially with the public), but the way the phrase is bandied about collapses all the layers you’ve outlined above and fails to describe how and why slavery was the cause of the Civil War and what that means. Sometimes, I wonder whether it is a sort of moral licensing: by stating it upfront you establish your credentials as a progressive, mainstream historian who then can proceed to act as a “traditional military historian” without confronting the difficult genealogy of the question.

Nice breakdown! This does a good job of pointing out how causes of conflicts are never really all that simple.