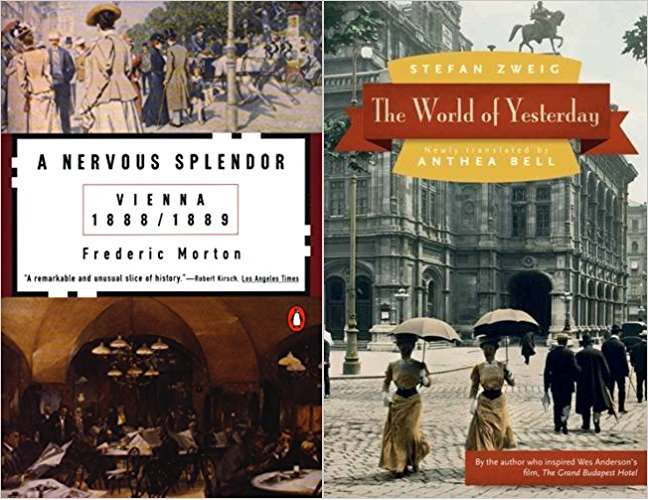

In my previous post, I took a moment to reflect broadly on the Austro-Hungarian Empire, an anachronism in its own time and an Empire very much lost to history, its legacy splintered across central and eastern Europe. As I explained then, imperial Austria’s history is of special interest to me for these very reasons which is why, not long ago, I read two books pertaining to its later history: A Nervous Splendor: Vienna 1888-1889, by Frederic Morton, and The World of Yesterday, by Stefan Zweig. While both were fascinating historical accounts in their own right, I found the majority of my thoughts upon concluding them on the present day.

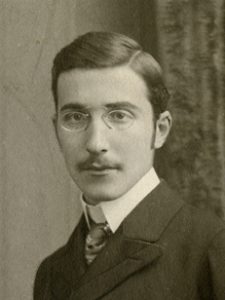

Morton’s book is an account, as the title suggests, of a small though lively piece of Viennese history towards the later part of the nineteenth century. Zweig’s picks up about where Morton’s leaves off, being his personal memoir which details life in Austria before and after the First World War, and in the opening days of the Second. In A Nervous Splendor, Morton examines the anxiety held by much of Viennese society at the turn of the century– a feeling of being left behind, unable to fully embrace economic, political, and social modernization in an Empire held together almost solely by ancient traditions. He represents this most keenly in Crown Prince Rudolf, the son and heir of Emperor Franz Joseph, whose liberal political leanings are stymied by his limited public role in the shadow of his imperial father, and whose romantic affair with the young Baroness Mary Vetsera stands at odds with his conservative, dynastic family life. In The World of Yesterday, meanwhile, Zweig fondly reflects upon a world that once was, in his view, secure, prosperous, international, and rich with art, music, and culture. Following the war, he saw it torn apart and replaced by a dangerous, suspicious, poverty-stricken, and insular one as Austria collapsed under its wartime losses. What Rudolf and Zweig had in common was their despair for a future, which consumed them both. The Crown Prince took his own life and that of Baroness Vetsera’s in a murder-suicide at age thirty, and Zweig killed himself 1942, only one day following the completion of his memoir: Rudolf for finding himself unable to pursue the future he hoped for, and Zweig seeing the world once more fall into a destructive and horrible war.

As I read these two accounts, it was impossible for me not to make comparisons to the present day United States. Regardless of one’s political beliefs, there is little denying the anxiety that seems to permeate society fueled by economic uncertainty and income inequality, fear of war and terrorism that leads to suspicion and distrust of perceived outsiders, and frustrating disconnects between the government and those they govern. For many the future feels vague and frightening. As I read, the struggle for modernity among the Viennese described by Morton felt analogous to the increasing computerization, specialization, and deindustrialization of America’s economy today, generating uncertainty among swaths of the population who see their ways of life changing, and fear being left behind. All the while, these changes are overseen by an older generation who are reluctant to embrace them: the political class of both the U.S. and Austrian Empire. Though A Nervous Splendor was written in 1979 — practically a century in the political sense — some of Morton’s concluding words feel remarkably fitting today:

[Rudolf] was the herald of an alienation common to the youth of our day. Over him loomed Franz Joseph, a storybook incarnation of The Establishment. Today The Emperor has been computerized into a system willing to grant its children lordly prerequisites and sexual license while remaining resistant to all essential reform. Under today’s system the young often appear to be a generation of Rudolfs: free and glamorous in theory, crushingly impotent in action, freely skeptical yet unable to establish one skeptic-proof premise; free to see themselves as unbounded individuals without ever arriving at successful individuality; free to press pleasure to numb excess; free to demand the absolute of their senses and their ideals only to be failed by both, overprivileged and hapless at once; free to sound the depths of sophisticated frustration.

In the previous presidential election, the young voted in astonishing numbers against Donald Trump, a candidate whose entire campaign was built around anxiety and fear, propelled by nervous voters clinging onto a world they believed was vanishing. It is this in this fearful world that today’s young are coming of political age, seeking reform and believing in some level of forward progress, as Rudolf did, but, as Morton puts it, made “crushingly impotent in action” by an administration that remains fully committed to looking only backwards. And yet it is easy for some to dismiss the political anxieties of the young today, for many do live comfortable lives, with access to technology, information, and other digital luxuries that past generations could only dream of. Personal luxuries not necessarily equate political satisfaction, though. Is internet and telephone access a suitable replacement for the independence of renting one’s own apartment, or living out from under the burden of loans and debt: realities that are growing increasingly rarer for the young as wages fail to keep pace with the increasing cost of living and education? Or for the equal treatment and rights of all citizens, regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, or sexual orientation– an idea enshrined in our founding documents, but which we have always fallen short at truly achieving? Much like the Crown Prince, comfortable circumstances do not make one an incompatible messenger for liberal ideas.

Comparing Zweig’s work places me in an even darker mood than Morton’s, and it is not something I approach lightly. Though he yearns for a past that is there no longer, I would never compare him or his ideas to today’s nostalgic movement: “Make America Great Again.” Many of the characteristics of Donald Trump’s presidency and political movement are, after all, the very same characteristics of post-war Austrian society that drove Zweig to the height of his anxiety for the future: a belligerence and disregard for other cultures, a suspicion and hostility to othered minorities living among us, and a degradation of politics. The past that Zweig reflected somberly on — his world of yesterday — was an international and multicultural one, where ideas and individuals rose to prominence without regard for their religion or ethnicity. This is, in many ways, a rosy view of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, as Germans still played a preeminent role in its operation, and pre-war Europe as a whole as racism and prejudice, after all, still existed before the wars. Nevertheless, he captures the idea of Europe before the battlelines of the World Wars were drawn, and before the excessive extremes nationalism of fascism fall across much of the continent. The recurring theme in his writing is the slow, insidious rise of such movements, transforming before one’s eyes from a miniscule, unimportant collection of extremism to a legitimate political force. Do many of us remember the moment when Donald Trump’s candidacy became a serious possibility instead of an amusing joke, as it seemed to begin? Are many of us surprised when white nationalists and Neo-Nazis appear in the news, after the events of the past year?

Zweig’s account is detailed, and come from a fascinating lens: a Jewish artist and pacifist with both a strong sense of internationalism, but also a strong Austrian and German identity. His central tragedy was both the recurring destruction of war and the changes it brought to society he loved, but also his departure from Austria in the face of the Nazi regime, where he had been considered a great luminary, now unwelcome. He does note a few changes following the First World War that were welcome, such as the increased rights women received and movements towards sexual liberation, though his story is otherwise almost entirely one of a world spinning out of control. Much like his age, the idea of internationalism is coming under suspicion today, as nationalism grows in prominence across the western world once again. Hopefully, there does not come a point where our own Zweigs begin to flee– hopefully, the above comparisons are only surface level fears. Historical comparisons to the present day make me uncomfortable, and I do admit a fair bit of discomfort having written this piece. No comparison can fully account for the full array of changes to society between any one period, and so outward similarities may mask deep differences that makes drawing too many or too steady of conclusions between a past event and the present day potentially dubious. And yet… the impulse to at least observe similarities where they exist remains.